It’s a ritual. Candidates for the presidential primary in New Hampshire head for the Puritan Backroom restaurant in Manchester to shake hands and greet customers who crowd the establishment. The Puritan is an unlikely name for a business two Greek immigrants started more than 100 years ago as an ice cream and candy shop. Through several incarnations, it blossomed into today’s spacious dining rooms. U.S. Congressman Chris Pappas, whose father, Arthur, runs the Puritan, is the fourth generation family member to be a partner in the Manchester landmark.

Without ignoring Greek food tradition, the Puritan unabashedly courts mainstream diners. “They come for the chicken tenders and stay for the politics,” writer Eunice Panetta aptly observed. (Chicken tenders are a wildly popular menu item—more about that later.) The story of the Puritan’s rise is a chapter in a larger saga. It is the tale of an immigrant community, once reviled as alien and its climb to a fully integrated and highly esteemed part of the fabric of Manchester.

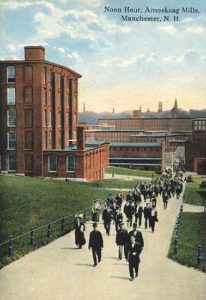

New England mill towns like Manchester were a magnet for Greek immigrants, who streamed in during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Companies in towns like Lynn, Lawrence, and Peabody needed factory hands and a succession of newcomers provided cheap labor. Manchester was founded as a textile town by a group of businessmen attracted by the abundant water power of the Amoskeag Falls along the Merrimack River. Patrician investors, like the Cabots, Lawrences, and Lowells, poured money into the project. The early industrialists, who had built textile mills in Lowell, Massachusetts, started constructing a vast complex that, by the 1900s, boasted 30 buildings and 17,000 workers. The Amoskeag Manufacturing Company rose to the heights of American industry. By the early 1900s, the 137-acre company was the world’s largest textile mill. (Amoskeag was a corruption of the Pennacook Indian word for this “place of many fish.”)

The magnates systematically planned the city to serve the requirements of their business. They planned its streets and parks around the axis of the factory. They imagined the city in paternalistic fashion. The company provided housing, playgrounds, and other municipal services for its charges. From the beginning, since skilled workers were in short supply, the textile colossus had to go abroad to procure them. Amoskeag, which specialized in gingham, flannel, and other cotton fabrics, recruited skilled workers who knew the tasks of the trade. Ezekiel Straw, the company agent, organized efforts to hire dye masters and weavers from England and Scotland, as scholar Aurore Eaton tells it. The mill placed ads in newspapers and circulated leaflets touting the bountiful opportunities in America: “Wonderful conditions at Amoskeag in Manchester, New Hampshire.” The ads pictured a mill worker leaving the yard with a wallet stuffed with cash, heading to the bank.

Not only craftsmen, but unskilled workers were vital for the mills. The employers brought in the Irish to build the mills and then to labor in them. French Canadians, fleeing rural hardship in Quebec, were signed up. The Irish feared that the French, who detractors called the “Chinese of the East,” would pull down wages. In time, the French, who by 1900 made up 60 percent of the work force, settled down in Manchester. They established their own parish church, credit union, and other institutions.

By the early 20th century, Amoskeag was hiring workers from southern and eastern Europe and the Middle East to cut costs. Greeks, Poles, Lithuanians, and Syrians joined the workforce. By 1910, the polyglot laborers spoke 28 languages. This suited the employers perfectly. The bosses often exacerbated the differences between the nationalities and ethnic groups by assigning them to separate work rooms. The divisions discouraged unified protest.

The Greeks, a large share of whom came from the rugged northern region of Macedonia, put up with harsh conditions and prejudice as the price of a path to opportunity. Many of the early immigrants were single men who left their peasant villages behind. Giorgios Kalampalis was one such greenhorn. As his uncle Spiros recounts in his book, The Dreams Come True in America, the 28-year-old was hired at Amoskeag in 1915 as a “greaser.” He was similar to other fresh recruits: They were “industrious, they weren’t lazy at all. When they looked for a job, they wouldn’t ask how much the pay was or how many hours they would be working.” The Greeks were taunted, Kalampalis recounts, especially by the Irish: “In the morning, as the Greeks were walking to work, the Irish would throw eggs at them through the windows and shout at them that they should go back to their home country.”

A Greek colony gradually was taking shape in downtown Manchester. The sojourners, who often dreamed of returning home with savings to buy property or to finance a sister’s dowry, were putting down roots. The Greek population was surging. The pocket of 300 immigrants in 1905 had burgeoned into a settlement of 1330 by 1910. By 1920, there were 3,000 new arrivals. The attractive opportunities in New Hampshire gave the small state a larger number of Greeks in proportion to the total population than any other, according to scholar A. Reed Carver.

The pioneers sent glowing letters home. The result was what researcher George B. Collins called “chain letter” migration. “Patriotis,” friends and relatives, joined fellow villagers in Manchester. Greeks identified with their village first and their country second. In 1903, people from Eptahori, an area in Macedonia that sent many residents to Manchester, founded a village association in their new home. They were not alone. Several village communities were “transplanted” to the Queen City, historian Tadeusz Piotrowski observes.

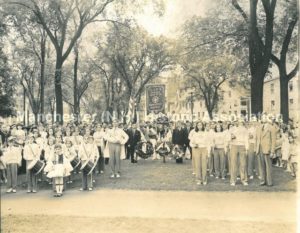

The Greeks clustered in the ten-block area downtown around Park Common (now known as Kalivas Park, named for the first Greek soldier from Manchester killed in World War I). Irish factory workers, who called the section Carrot Field, had settled earlier in the neighborhood’s tenements and boardinghouses. Although other ethnics, Poles and Syrians, dwelled nearby, Greeks were increasingly becoming the majority. Conveniently located a short walking distance from the mills and a cheap place to live, the area around Park Common was inviting. Most important, the Greeks were seeking security by huddling together. “Greektown,” as scholar Collins puts it, “was a refuge for immigrants from the alien and sometimes hostile society around them.”

The immigrants shaped their settlement in the image of their ancestral homeland. To the Greeks, Park Common was their “mesochori,” the village square. It was the focal point of their ethnic enclave, a place to congregate, catch up on news, and relax from the stresses of the daily toil.

Nearby ethnic businesses and cultural institutions created a cohesive community—agoras (markets), butcher shops, and grocery stores sprang up. The immigrants banded together to buy the land for the Assumption Orthodox Church. Several coffee shops (kafenia) provided a refuge for homesick men seeking companionship and solace in an often unwelcoming city. “Spruce Street lined with coffee houses in which men from Land of Homer gather; here proud of their race and industrious as a whole,” the Manchester Union newspaper recorded in 1910. They came to talk, dance, and drink strong dark coffee in these gathering places. The kafenia offered their customers practical help, long-time Manchester journalist and now executive director of the Manchester Historic Association, John Clayton, remarks: “You could play a couple hands of xeri or pick up a copy of Spiros Cateras’s local Greek newspaper but a coffee house also served as a vital employment office where George Copadis (The Elder) helped immigrants.”

Bridling at the thought of a lifetime of factory jobs, many Greeks launched their own businesses. They worked as coffee grinders, confectioners, produce merchants, plumbers, tailors, and billiard hall owners, among other occupations.

Purveyors of traditional foods nourished the neighborhood’s denizens with memories of home. “[We] remembered a simpler time when there were … lambs hanging in Nassika’s butcher shop, black olives at the Tyrna market, and freshly baked bread at Copadis’ bakery,” Spiros Plentzas and Chris P. Kehas, the authors of The Spirit of Kalivas Park, remembered the district during World War I. The exotic sight of “Greek and Oriental pastry displayed in sweet shops” fascinated a writer in the WPA book on the “Granite State.”

Greeks in Manchester clung to village customs and traditions. Simple repasts were enriched with age-old techniques. Evanthea Keriazes followed her mother’s practices when making her children “grass pies.” The “leaves” (filo pastry) were filled with eggs, cheese, and spinach, she recalled in an interview with the WPA during the 1930s. In Manchester, she said, families carry on “our gaieties in our homes,” lacking “village squares to dance in.”

After the Easter church service, Keriazes joined with friends and relatives “exchanging Easter eggs dyed red to symbolize joy and by crying ‘Christ is risen’ and ‘He is risen, indeed.’” On Decoration Day, 49 days after Easter, “wheat cakes … large cakes made from sugar and beautifully designed,” were carried to the church.

The day before Christmas was a festive occasion. A pig was slaughtered and the remaining lard was preserved so that it would last through the year. “We children do not like pastry made from ‘store’ lard and often refuse to eat it.” In Greece, pies required shortening “of the right consistency to make the rich, flaky crust we needed.”

The tight-knit community was all too frequently greeted with suspicion and anger. A 1910 Manchester Union article that writer John Clayton uncovered depicted the Greeks with xenophobic glee. “The most foreign of the foreigners now in this city in large numbers are the Greeks,” the anonymous author put it. “The average citizen knows the Greeks here in Manchester as the man who blacks his boots … or who makes and sells confectionery and ice cream soda cheaper than the ordinary white man in the business,” the writer continued. “The police say that a Greek is industrious, energetic, and generally useful except when he lingers too long in a Spruce Street coffee house or indulges too freely in the wine that is red.”

Antagonism between the Greeks, the newcomers to the mills, and more established groups like the French and especially the Irish was intense. They blamed the Greeks for working more cheaply in the textile and shoe factories and for stealing their jobs. When Greeks in 1903 were recruited to break a shoe strike, the incident reinforced fears of the newcomers. Their neighbors complained that the outsiders harassed their wives and daughters. “They tell of women held up on the street and vile insults offered,” The Manchester paper, the Mirror, reported.

Ethnic animosity was not new to Manchester. The Irish, who poured into the mills after the potato famine of the 1840s, faced hostility. On July 3, 1854, anti-Catholic marauders were bent on burning the St. Anne parish church. Journalist Clayton carries on the story: John Maynard, “the city’s leading contractor at the time, was able to disperse the crowd, partly because he held the working future of many Protestants in the palm of his hand. Perhaps more importantly, he held a gun in the palm of his other hand.” The Know-Nothings, a fiercely anti-Catholic political party, had a large enough following in Manchester to elect Theodore T. Abbot, one of their own, as mayor in 1855.

Park Common, the heart of the Greek community, was the scene of ethnic battles between “warring races,” as the Mirror indelicately put it. The Greeks considered the common as their turf. The Irish thought otherwise. “The Greeks who swarm so thickly in the boarding houses down Spruce street and elsewhere in the vicinity would like the common as their own backyard,” a Mirror reporter observed.

Clashes were inevitable. On July 11, 1905, a fracas on the Common exploded in violence. Although accounts differ, a common thread involves a Greek who was hit by an errant baseball thrown by a group playing catch. Tempers flared. Greeks were chased in a melee in which some of their assailants drew knives and threw brickbats.

The press painted the battle as a “race war.” The Mirror headline read, “Riot of Races Broke Out Last Night on Park Common.” Although the Greeks suffered most from the fighting, they made up the majority of those arrested. There was a definite ethnic tinge to the riot. Two of three men ultimately charged in the case, John Sullivan and William Sweeney, had distinctly Irish names.

The Manchester police, operating like an arm of the Amoskeag company, kept a sharp eye out for immigrant misbehavior, especially by the Greeks. Ireland-born Michael J. Healy, the city’s first police chief, appointed in 1895, kept detailed records of lawlessness, historian Scott Roper reveals. Although the English, Irish, and French committed offenses, the police log book highlighted the ethnicity of other miscreants. Greeks, Roper notes, were suspected of “stealing wood and coal.” Theft of bottles of milk, or, in one case, a saucer of milk, were blamed on the aliens.

Authorities, like Chief Healy, were especially fearful of Southern and Eastern European immigrants, in their eyes a particularly truculent group. Rattled by the 1905 “race riot,” he worried that these workers would be receptive to a radical labor message. The Wobblies, the Industrial Workers of the World, or I.W.W., had spearheaded a militant strike among the widely diverse immigrants in Lawrence, Massachusetts, a nearby mill town.

Undeterred by the hostile climate, entrepreneurially minded Greeks pushed ahead. Two friends from Northern Greece, Arthur C. Pappas and Louis K. Canotas, who had worked together at a remnant store in Elassona, arrived in Manchester in 1906. They took jobs in the city’s mighty industries—textiles and shoes. Pappas found work in an Amoskeag mill, while Canotas was hired at a factory owned by the McElwain Shoe Company. (The firm, in the second largest industry in Manchester after textiles, became famous for its Thom McAn line of shoes.) They were eager to strike out on their own. Canotas opened a shoeshine parlor, a frequent launching pad for Greek immigrants. Pappas left Manchester to operate a fruit and candy shop in Natick, Massachusetts. The friends soon launched a series of shops from which today’s Puritan Back Room is descended.

The Puritan Confectionary Company was their first venture in Manchester. It opened on April 5, 1917. Making homemade candy and ice cream, the founders joined a legion of countrymen whose shops dotted the corners of small towns and big cities in the early 20th Century America. The name Puritan appealed to them. Congressman Chris Pappas, Arthur’s great grandson, thinks he knows why they chose it. “I think they wanted a name that grounded them in New England and sounded very American,” he said in an interview on New Hampshire Public Radio. The early shop, established on the eve of America’s entry into World War I, faced hurdles but overcame them. Because of rationing, Chris’s father Arthur told writer Jack Kenny, “They had to buy sugar on the black market. How do you make money without sugar?” Their products were popular because the owners stuck to the basics, the chocolates and vanillas. The two businesses nicely meshed—peppermint and maple walnut were equally good for candy and ice cream.

Two years later, the compatriots went into the restaurant business. They landed a perfect location, across from City Hall. “It was a kind of favorite spot,” former Mayor Sylvio Dupuis tells journalist Kenny. “For people working or doing business in Manchester, it was at the top of the list of places for having lunch.” At this time, people thronged downtown, Arthur Pappas added. “Monday and Thursday nights were the busiest. That’s when all the stores stayed open at night.” Thursday, he pointed out, was the day mill workers were paid. “People did their shopping downtown, their banking, you went to the movies downtown, everything was downtown.”

A young newspaperman in post-World War II Manchester became a Puritan regular. Ben Bradlee, the late executive editor of The Washington Post, writes in his memoir, A Good Life, of a “Greek greasy spoon joint where the hamburgers were cheap and the waitresses were pretty. (Where are you now, Jo?)”

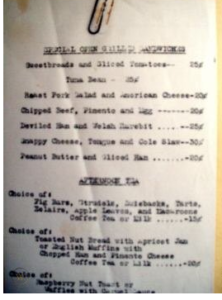

The Puritan also offered customers a more sedate setting. A 1937-38 menu listed an array of open grilled sandwiches, like Deviled Ham and Welsh Rarebit, Chipped Beef, Pimento, and Egg, and Peanut Butter and Sliced Ham, priced at 20 and 30 cents. The restaurant served an Afternoon Tea. Among the choices were Toasted Nut Bread with Apricot Jam and English Muffins with Chopped Ham and Pimento Cheese. The Puritan called itself a Restaurant and Tea Room, a name with a New England ring.

The Greek merchants would leave the once-bustling downtown behind. Shops were departing for the suburbs and new businesses were avoiding the city center. Seeing the writing on the wall, Pappas and Canotas decided to move. In the late sixties, the partners moved their operations to Daniel Webster Highway, where they already were operating an ice cream stand.

The Puritan concentrated on quick items for the carry out trade. Hot dogs, lobster rolls, and pizza pulled in customers. Ice cream, the eatery’s hallmark, continued to tantalize patrons. The sweet is “what got a lot of our customers coming in the first place,” Plato Canotas, son of founder Louis, told journalist John Clayton.

In 1974, the owners opened a full-service restaurant, which they called the Puritan Backroom, because the entrance was in the back. (The Front Room was the section devoted to takeout.) The vast, sprawling 240-seat restaurant housed several dining rooms and a bar. The Puritan also added a conference center to bring in more business.

The Puritan sold itself as a family dining room with ample helpings, reasonable prices, and familiar food. Like the diner and many other Greek food businesses, it offered a wealth of choices, from roast turkey to lasagna. Giving a nod to its own culinary traditions, the Puritan sells spanakopita, tzatziki, and fried feta, in addition to other items, like nachos, buffalo wings, potato skins, and shrimp cocktails, to snack on. Another specialty is mac n’ cheese with a Greek accent. The touch of cinnamon in the dish signals its debt to pastitsio, a classic Greek casserole. New England standbys like haddock, clam chowder, and lobster pie share the menu with lamb kebabs.

One dish with no specific Greek connection has become a crowd pleaser. Chicken tenders, grilled or fried, as a salad feature or pizza topping, are a menu centerpiece. (Chicken tender parmigiana or cacciatore are other alternatives.) Charlie Pappas created them in 1974, according to son Arthur. “We were selling boneless breasts of chicken, and our supplier was ending up with a lot of little pieces he didn’t know what to do with. So my dad … said I will come up with an idea, and we started selling Chicken Tenders,” he told New Hampshire Public Radio. Instead of discarding the strips left over from preparing a boneless chicken breast, the Puritan, after marinating, seasoning, and frying them, fashioned a singular plate. Arthur’s son Chris also admired Charlie’s inventiveness. “My grandfather considered himself a pioneer when it came to fried chicken…. It turns out that the byproduct of something else became the focus of the menu,” he said to journalist Nik DeCosta-Klipa.

The tenders can be perked up with one of several flavorings—coconut, buffalo, or spicy sauces. The Puritan conjured up its own “special sauce” for the dish that combines soy, olive oil, and unenumerated spices. Many patrons dub the condiment duck sauce. Chris Pappas calls it “sweet and sour” sauce.

The ingredients in the flavoring remain cloaked in mystery. The secrecy surrounding it is reminiscent of another confection, the “Coney Island” sauce draped on hot dogs in Greek eateries. Arthur Pappas guards it vigilantly. “It’s written down in the safe, so if something happens to me—if I go—if I go away on vacation, I try to make a little extra, just in case the plane crashes,” he told the NPR station. “They can still bury me, and I can have my special sauce at my funeral.”

Another Puritan calling card, frozen mud slides, highlight a meal. The drink that some have called called a “booze infused” cocktail is typically made with vodka, Kahlua, and Baileys Irish Cream. Slides come with different flavors—Almond Joy, Snickers, and even Churro. The appetite for the drinks was so insatiable that, in 2011, the Puritan was the country’s largest purchaser of Baileys.

Homemade ice cream tops off a dinner. The Puritan markets such New England treats as maple walnut and grape nut and wows customers with novel flavors like baklava, Cherry Seinfeld, and Moose Tracks.

The proprietors have assiduously built up a loyal clientele hosting birthdays, anniversaries, and family functions. The Puritan lavishes attention on customers. “We all need repeat customers. When you meet a customer for the first time, you treat them like your favorite relative,” Arthur Pappas commented to journalist Kenny.

Employees also required special attention. Younger workers often found their job at what writer John Clayton called “Puritan Prep.” The restaurant fostered loyalty among its workers by encouraging their education. Puritan employees chalked up their success to its tutelage, journalist Kenny discovered. “I had to maintain a B average to be able to work here,” Sheila Macdonald, a former worker, said. Another hire, Moises Montes, a Salvadoran, enrolled at Central High School, at owner Plato Canotas’s urging. Puritan paid for his English classes at University of New Hampshire, Manchester.

The combination of political electricity and hearty food has enhanced the Puritan’s fame. Ever since the advent of the New Hampshire primary, the Puritan has grown into a mandatory stop for candidates, Democrat and Republican. The opportunity to meet and great locals in a family restaurant that exudes hospitality has been hard for vote seekers to refuse. Mingling with “regular” people, reporter John DiStasio, a veteran New England journalist, observes, is a major draw. “It’s not like some white table cloth sort of place,” DiStasio told writer Nick DeCosta-Klipa. “They have really good food, and the place is really crowded.”

The Puritan was a unique restaurant. “Right from the beginning, politics was infused into the business,” co-owner and Congressman Pappas remarked to political reporter Chris Cilizza.

From an early age, politics pulsed through Chris Pappas’s life. He was an early fan of Mike Dukakis: “I remember being at school, and Dukakis and Tsongas [former Senator from Massachusetts] were there,” he reminisced to writer Panetta. “In my second grade class, people were lining up outside the windows, and I literally made several paper airplanes that said ‘Dukakis’ on them, and threw them out the window at the people down below, probably violating all election laws.”

He worked as a youngster at the Puritan, where he sharpened his political antennae: “You get a sense of people in an environment like this, you get a sense of who is genuine and who is a politician,” Chris explained to Panetta. “People in New Hampshire understand how to deconstruct candidates and get to the core of who they are.” His restaurant apprenticeship prepared him for campaigns for elected office. He won a contest for New Hampshire State Representative and secured a position on the state’s Executive Council. His state jobs were a springboard into national politics. Chris, who is openly gay and a liberal Democrat, was elected in 2018 to represent New Hampshire’s 1st Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Stories of suitors for national office, Democratic and Republican, are part of Puritan folklore. Customers recall candidate Joe Biden sampling the restaurant’s popular ice cream on February 8, 2020. Sargent Shriver typically ended a day of campaigning tucking into a plate of lamb kebabs. Hillary Clinton made frequent pilgrimages to the Manchester restaurant. Her husband arrived one late evening in 1992 and ended up bantering with the cooking staff and watching a basketball game on TV. President George H.W. Bush descended on the Puritan in 1992 with his Secret Service entourage.

Hillary Clinton did more than woo customers at the restaurant. She used its facilities for her political operation during the 2008 primary. The candidate transformed the restaurant conference center into a call center, journalist Cilizza notes. She organized a get-out-the-vote rally in the restaurant’s parking lot. “I like to think all the chicken tenders and coffee for her volunteers fueled her upset victory,” Chris Pappas told the reporter.

The Puritan story provides important lessons about American politics, Cilizza believes: “The Puritan and its political history and chicken tenders speaks to the centrality of retail politics in running a presidential campaign.”

Greeks have played an influential role in New Hampshire politics. Chris Spirou, a former New Hampshire minority leader in the state senate and former chairman of the state Democratic Party, credits Hillary Clinton’s New Hampshire primary victory to Greek voters. Spirou, who once washed dishes at the Puritan, argues that Greeks voted 9-1 for Hillary. Her campaign manager, he notes, was Greek, and Chris Pappas was her top delegate. Speaking to writer Apostolus Zoupaniotis, Spirou remarks that Clinton told him that “the community played an important if not a decisive role in this election.” Greeks looked to politics as a route to advancement in America. Just as it had been for the Irish, writer Clayton observes, politics was a “tool of assimilation.”

The owners of the Puritan achieved recognition not only as restaurateurs, but also as civic leaders. They have promoted local nonprofits, backed civic clubs, and supported baseball teams. The Puritan’s achievements paved the way for the wider acceptance of the Greek community. Other prominent Greeks in Manchester have raised its standing. Among the notables are the aforementioned politician Chris Spirou and his brother Stan, the former coach of the Southern New Hampshire University men’s basketball team, former Manchester mayor Ted Gatsas, and George Capodas, the state Commissioner of Employment Security. Greek sports heroes like Gus Zitrides, John Kilonis, Spike Papageorge, and Andy Prutsalis have won friends for the ethnics.

Manchester, like other factory towns, is in the throes of change. Older ethnic groups are moving out of the center city. Department stores and modern apartments supplanted the aging housing of Park Common. Greeks have dispersed, leaving their once-vibrant Manchester neighborhood behind.

An influx of new immigrants has introduced the Queen City to unfamiliar cultures. Ethnic eateries from Cuba, Mexico, and the Dominican Republic have set up shop. Adventurous diners can sample Nepali fare and buy Bulgarian and Bosnian foods at a downtown grocery. One of these businesses, although marginal now, may develop into a welcoming city institution, a future Puritan.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

John Clayton, executive director of the Manchester Historic Association, was an invaluable source of information and anecdotes about his hometown. His writing sparked my interest in the subject. Arthur Pappas took time away from his business to relate the story of the Puritan. Theresa Kinsey, Information and Technology Librarian at the Manchester City Library, generously aided this writer in his quest for often hard-to-find materials. Daniel Peters, Research and Facilities Manager at the Historic Association, gave me valuable background. Meletios Pouliopoulos, who directs the nonprofit Greek Cultural Resources, offered help and support.