I pulled the bottle of yellowish soda from the cooler and joined the line of customers waiting to order at el Pollo Sabroso, a restaurant in Washington, D.C.’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood that specialized in grilled chicken Peruvian style. I was following the advice of a Peruvian friend and buying Inca Kola to go with this dish. With pollo a la brasa, this fervent fan of the national drink said, Peruvians must have Inca Kola. In his homeland, no polleria or chicken vendor would even carry Coca Cola. I was puzzled about why Peruvians, locals and émigrés alike, were so passionately loyal to this mass-produced soda. The affection seemed odd in a culture where the homemade and the traditional were so esteemed. I set out to investigate.

Credit a Yorkshireman with introducing Peruvians to this peculiar drink. In a country of immigrants—a land whose Presidents included Kuczynski, Toledo, and Fujimori—new arrival Joseph Lindley hardly stood out. Lindley and his wife Martha arrived in Lima in 1911. A product of Doncaster, a North England coal town, he opened a small shop purveying carbonated soft drinks. The Santa Rosa Draft Company manufactured Orange Squash, Lemon Squash, Champagne Cola, and other beverages.

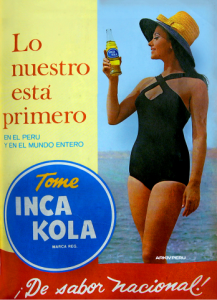

After tinkering with various products, Lindley threw himself into concocting the liquid creation that was to become Inca Kola. Keenly attuned to the Peruvian national spirit, the entrepreneur launched Inca in 1935, a festive year in which Lima’s 400th anniversary was being celebrated. In a display of marketing genius, Lindley identified his product with the nation’s heritage. An Inca Indian figure would grace the bottle. The drink’s distinctive yellow color evoked the sacred rays of the sun. Over the years, the company promoted the drink with such tag lines as “Es Nuestra” (“Its Ours”) and “Inca Kola, The Drink of National Flavor.” In an interview with the Huaraz Telegraph, an English-language Peruvian newspaper, Joseph’s son Johnny recalled the business’s winning strategy: “We knew how to communicate to the people that we felt like part of this country. In the days of terrorism we would say that Inca Kola was the flavour that united, it gave us strength, when in times of pain it became the flavour of joy, the flavour of the party.”

Peruvians testify to the emotional ties the drink inspires. Rafael Garcia explained his loyalty to Inca Kola to Calvin Sims of the New York Times: “I drink it because it makes me feel Peruvian. “I tell [my daughter] Gabby: This is our drink, not something invented overseas. It is named for our ancestors, the great Incan warriors.” Sims offers up a priceless anecdote to illustrate Peru’s Inca mania. A passenger on a flight from Buenos Aires to Lima was aggravated when the airline ran out of his favorite drink. “Drink something other than Inca Kola—that’s sacrilege you are suggesting. That’s like an Argentine eating beef from Bolivia, or a Brazilian wearing Bermuda shorts to the beach.” He finally gave up and ordered a Sprite. “You got any yellow food coloring to go with that?”

The soda, which Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges called “a simply implausible drink,” might seem like a tough sell. Some have likened its taste to bubble gum. Inca, one of whose ingredients is reported to be a popular herb, Hierba Luisa, used for making tea, partakes of the plant’s lemony flavor. Crucially, the drink appeals to the Peruvian sweet tooth. To succeed in the Andean nation, Coca Cola had to increase its beverage’s sugar content.

For all its commercial ingenuity, the company had to fight a tough battle with Coca Cola for supremacy. Coca Cola, which had originally fortified its product with extracts from Andean coca leaves, ruled the market. Other local brands like Kola Inglese and Triple Cola vied for customers. Susy Kola, a drink named for exotic dancer and legislator Suzy Diaz, was another favorite.

In Peru’s “Kola Wars” the interloper, Inca Kola, cast itself as the underdog against the Coca Cola leviathan. Inca peddled its brew to restaurants, snackbars, and small picanterias. In one victory, the soda broke into Bembos, a fast food chain, and overcame the resistance of McDonald’s, which had an exclusive relationship with Coke

Inca Kola shrewdly associated its product with Peru’s diverse dishes and eating. The drink was portrayed as the perfect accompaniment to Lomo Saltado, a stir-fry of beef strips, onions, tomatoes, and potatoes suffused with soy, garlic, and cilantro; Aji Amarillo, chicken prepared in a nutty chili-laced sauce; and other national specialties. Converting the country’s many chifas (Chinese eateries) to Inca was a major victory. (Surprisingly, Peru has a large Chinese population, which originated in the mid-nineteenth century when Spain imported laborers as replacements for the recently freed slaves to work in the plantations, guano mines, and other jobs.) In many of these outlets, the new soda was the only bottled drink served. “Chifa without Inca Kola just isn’t Chifa to most people,” the Huaraz Telegraph put it.

Coca Cola finally capitulated to Inca, one of the few victories in which a national drink was able to best the global giant. After attempting to buy out its rival, Coke agreed in 1999 to buy a 50% share of its rival for $300 million. It also took control of Inca’s overseas marketing and production. Inca continues to beat Coke in the Peruvian market.

A victory celebration soon followed. Coca Cola CE0 M. Douglas Ivester traveled to Lima to announce the agreement. In a symbolic gesture, the executive, no fan of the soda, drank a glass of Inca at a press conference. “Coca Cola’s President Toasts with Inca Kola,” one newspaper headline exulted. The reluctant businessman was rumored to have muttered “looks like pee, tastes like bubblegum.”

In the hands of business analysts, Inca’s success story has become an attractive case study. “The success of Inca Kola also reflects the uniqueness of Peruvian consumers who tend to have very strong ties to products that they associate with personal and national identity,” an essay from the Wharton School of Business Management at the University of Pennsylvania contended. Inca’s triumph, business school professor Gerard Costa observed, demonstrated how a company can beat back the forces of globalization. “Globalization, during times of economic weakness—such as Peru during the 1980s and 1990s—led consumers to identify with their local products.”

The secret behind the brand’s success isn’t really that complicated. Inca strikes a sentimental chord in its buyers. “Inca Kola runs through the veins of Peruvian babies—and that is not an exaggeration,” Peruvian chef Hajime Kasuga told the Financial Times.

A Brief Note: The words in Peru for soy sauce (siyau) and ginger (kion) are not the normal Spanish terms, but are taken from Chinese.

June 2015