Mauritius on My Mind: A Culinary Voyage

Flavorful dipping sauces at Aux Iles Bleues in Montreal

Coconut, mint, and lime; birds-eye chili pepper; tomato, shallots, and cilantro; peanuts and tomato. Toussaint Attiave carried a plate with four bowls of these tantalizing dipping sauces to our table on the terrace of his recently opened Montreal restaurant, Aux Îles Bleues (“The Blue Islands”).

They were chutneys (chatinis in Creole), he said, traditional starters that whet the appetite for the main meal in Mauritius, his Indian Ocean island birthplace. The chutneys came with a basket of pieces of toasted pita bread. The bread in his homeland, Toussaint added, would have been roti (a generic word in Indian languages for bread, adopted in Creole, the Mauritian tongue).

Toussaint had come to Montreal in 1976 to study engineering. He decided to stay after meeting a “beautiful Quebecoise” woman, Dominique, whom he married. Some of her paintings hang in the dining room, which is painted in shades of blue with red accents.

The colorful dining room at Aux Iles Bleues in Montreal

Passionate about cooking, he opened a restaurant, Café Classico, in the town of Sherbrooke. His new venture in Montreal’s Plateau neighborhood highlights the cuisines of the Indian Ocean islands of Seychelles and Réunion and features the food of Mauritius.

The restaurant offers patrons a choice of cooking sauces, which include Creole, Tandoori Masala, and Coco Seychellois, to accompany either seafood, pork, chicken, or other mains. I decided on Mauritian cari, to invigorate squid, shrimp, and scallops. His curry, Toussaint remarked, had a healthy dose of cumin and coriander seed. “Everybody eats curry” in Mauritius, the restaurateur noted.

I was delighted to find a Mauritian restaurant. The volcanic island, 1200 miles off the eastern coast of Africa, had long fascinated me. I fantasized about its rich diversity. Imagine an island over two-thirds of whose population is of Indian background. Indians live with a much smaller group, the Creoles, which traces its origins to Africa, as well as with a community of Chinese. What kind of food, I wondered, would spring from this heterogeneity?

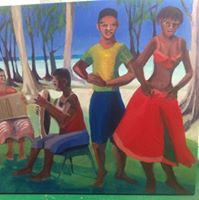

A painting by Toussaint’s wife Dominique at Aux Iles Bleues

In my Mauritian quest, I bought guidebooks, cookbooks, and historical studies of the island. I searched for Mauritian eateries not only in Canada but also in Marseilles and London. The Indian Ocean island, I discovered, had enchanted many writers. Mark Twain, impressed by its “luxuriance of tropic vegetation,” spoke of its many ethnicities: “French, English, Chinese, Arabs, African, East Indians, half-whites, quadroons.” He talked to an islander who told him that “Heaven was copied after Mauritius.” The French poet Baudelaire, who had been banished to India by his father “to be cured of love,” left the boat in Mauritius. He extolled “a perfumed country that the sun caresses.” He rhapsodized about “purple trees,” palms, that “weep idleness,” and “dark enchantresses.” Another visitor, Charles Darwin, observed that “the various races of men walking on the streets offer the most interesting spectacle.”

It was during the year I spent teaching in a refugee school in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, that the seeds of my enthusiasm for Mauritius were first sown. The East Africa city was part of the same Indian Ocean neighborhood as Mauritius. Dar was a port city along the country’s Swahili coast where African, Indians, Arabs, and Persians had all left their imprint. This was not the stereotypical one-dimensional “dark continent” I had expected.

Dar had a large Indian quarter where the Asians lived and sold their wares. One evening, I was treated to a hot curry at the home of an Indian Muslim family, whose son was a friend. The family shop, as was often common, sat below their apartment. Indian food was not foreign to the city’s taste. I was surprised to find a local eatery, the Cozy Café, selling samosas.

The Indians had dispersed throughout the country. Traveling outside the city, I noticed the inevitable dukas, their general stores, which sold everything from brooms to dried fish.

I grew restless with the African food served at the school. Lunch was invariably ugali, a dish of mashed up maize with gravy, a kind of Tanzanian fufu but without the spicy sauce. I hungered for more exciting fare. I discovered Haleeds, a small eatery run by an Arabic proprietor. For a few coins, I enjoyed mishkaki, spiced cubes of barbecued beef that were cooked on a small grill outside the shop. It came with chapati, an Indian flat bread. I washed down the meal with a glass of fresh passion fruit juice.

I pursued other adventures. When a fellow teacher married a Punjabi woman, I went to their wedding and was introduced to one of Dar’s most vital communities, whose roots went back to the early Sikhs recruited to build a railroad in East Africa.

Surrounded by the Indian Ocean, I was excited to live in a gateway to mysterious lands. Lured by the romance of the port, one evening a friend and I roamed the vast expanse of the docks. Ships regularly left East Africa for India. On a visit to Mombasa, the Kenyan port city, I stared with amazement at a boat in the harbor, whose top deck was packed with Asian families. They would sleep and eat their meals on the deck over the long voyage.

Nearby islands also beckoned. I visited the island of Zanzibar, once a center of the slave trade and the world’s top exporter of cloves. As I walked through the harbor, I could smell the aroma of the pungent spice. I explored the narrow streets and gazed at the intricately carved doorways of Zanzibar Town, the capital of an island once ruled by the Sultan of Oman.

I rode out in a taxi to the outskirts of the city. We passed coconut trees whose shells dotted the ground. As we walked outside, I detected the unmistakable fragrance of lemongrass. The driver peeled off the bark of a cinnamon tree to show me.

My appetite for future island trips was whetted. Cruise shops frequently stopped at Dar to pick up passengers who wanted to visit the Indian Ocean islands of Mauritius, Réunion, and the Seychelles. Unfortunately, I missed this opportunity and ever since I have regretted it. I was especially curious about Mauritius and could only imagine its blend of flavors and cultures. Short of a trip there, I would have to make do with a vicarious excursion. Perhaps an outing to a Mauritian restaurant would satisfy my desire.

The dining room at Toronto’s Blue Bay Cafe

Finding such an exotic eatery was not simple. It would be at least fifteen years before I uncovered one. It was, ironically, in Canada, home to many Mauritian emigrés, not in the U.S., that I reached my culinary destination. Planning an early trip to Toronto, I called the Mauritian embassy in Washington on an impulse to see if the city had any eateries serving the island’s food. An official suggested I try Toronto’s Blue Bay Café.

One early evening after our arrival in the city, my wife and I embarked on an expedition to find the dining room. We took a trolley car to the end of the Dundas Street line. Looking out the window, I saw signs in Portuguese advertising restaurants, cafés, and other businesses clustered along several blocks. We got off at the last stop and walked from the switching yard through several gritty blocks to the Blue Bay.

We climbed a narrow staircase to a small room, modestly decorated with travel posters. The unusual menu, which transported us to the Indian Ocean world, made up for the lack of atmosphere. It listed samosas among the starters, an early clue to the provenance of the food. I dug into an achard, a pickled salad of cabbage, carrots, and other vegetables. I had encountered variations of the piquant mix in Malaysian, Indonesian, and Thai restaurants—all with similar names. The Creole word, achard, descended from the term for pickled foods in several Indian languages. Achar, the Indian name, likely has a Persian lineage.

The pickled appetizer has wide appeal in Mauritius. It has even entered the island’s folklore. An official letter, according to cookbook authors Paul Jones and Barry Andrews, was sent from the island to the Queen. It was returned because of a yellow stain on the envelope. The color probably came from either turmeric or the mustard seeds in the relish.

Another item on the Blue Bay menu, Fish Vindaye, also had an odd backstory. Vindaye, a Creole word, stemmed from an Indian delicacy, vindaloo, created in the Portuguese colony of Goa. The Iberians introduced one of their specialties, vina d’alho, meat steeped in wine vinegar and garlic, to their subjects and the Goans reinvented it. They spiced the dish with saffron, mustard seeds, chili, and other flavorings. Indians took it to Mauritius. “On Maurice the name got ‘Frenchified’ into ‘vin d’ail’ and ended up as ‘vindaye’ in Creole,” the Dutch website Coquinaria points out.

Other Blue Bay offerings suggested other histories. The restaurant sometimes prepared daubes, braised chicken or other meats that had a definite French note. The menu’s mines frite, a noodle stir fry with shrimp, reflected Chinese technique. The owners, I learned, were of Chinese background, a fact whose significance I did not yet fully grasp.

Stir-fried noodles at Les Delices de L’Ile Maurice

The Blue Bay, now closed, was an initiation into Mauritian cooking. I still had much to learn. Some years later, on a trip to Montreal, Peggy and I had another Mauritian adventure that was as much performance as culinary experience. After a long trek from the Verdun Metro station in eastern Montreal, through a down-at-the-heels area with many “à louer” [“for rent”] signs, we reached Les Délices de l’île Maurice. We were greeted by a portly gentleman of Chinese background, Sylvestre Ng-Kan, who wore a Hawaiian shirt and Bermuda shorts. The effusive chef, who had trained in Montreal restaurants, showed us a large map of Mauritius and regaled us about his country. The restaurant had little formal menu. Sylvestre asked what kind of sauce we would like—Creole, curry, etc.—and what type of fish or meat. My memory gets hazy then, but I do recall that one of the sauces was redolent of cloves.

Before we could order, we were given a complimentary bowl of tangy yellow split pea soup. It reminded me of dal sorba, the lentil soup that is a fixture of many Indian restaurant menus. But the connection between the soup and the larger mosaic of Mauritian food was still blurry.

Several years later, my wife uncovered a Mauritian restaurant that had recently opened on Montreal’s Boulevard St. Laurent, the “Main,” as locals called it. The city’s main north-south street had once been considered a divide between the French- and English-speaking communities. La Ravanne (named for a Mauritian musical instrument) was located in an area where many ethnic restaurants had sprouted.

One dish at the eatery especially captured my attention. The gâteau piment (chili cake) sounded French, but the taste and the ingredients of the popular Mauritian snack spoke of its tropical parentage. These doughnut-shaped fritters, made from yellow split pea flour, had an Indian feel to them. The crunchy and spicy starters were accompanied by a yogurt salad of cucumbers and carrots. At the time, I thought little of the appetizer. Looking back now, I suspect that it was kin to raita, a similar Indian dish. One other characteristic stood out. The owners of La Ravanne, like those of the Blue Bay and Les Délices, have Chinese roots. (The restaurant, unfortunately, is no longer open.)

Painting by Toussaint’s wife Dominique

Intrigued with its food, I gradually learned that its story was inextricably connected to the island’s history. Mauritius had been shaped by a succession of invaders and peopled by diverse ethnic groups. It was uninhabited. It had no “aboriginals,” Toussaint observes. Its cuisine was the result of the intermingling of cultures. Without a fixed identity, the islands would have to forge their own.

The Portuguese, early voyagers seeking a route to the spice treasures of India, stumbled on Mauritius in 1507. Ship captain Diogo Fernandes Pereira called it the Ilha do Cerne, the Island of Swans. (The island actually had none of these birds.) Except for using it as a refueling stop, Mauritius had little interest for the Portuguese.

The Dutch, also traders, established a more permanent presence. Seizing control in the early sixteenth century, they named the colony Mauritius after Prince Maurice von Nassau, their ruler. The Dutch transplanted sugar from their Indonesian possessions. Although the crop would ultimately flourish and become the foundation of the island’s wealth, it provided little in the way of short-term returns; the Dutch grew impatient and moved on.

The ill-fated dodo bird

They stayed long enough to hunt one of the island’s few indigenous species into extinction: the ungainly, flightless bird they called the doudou, their word for “stupid” (the creature’s name was later changed to dodo). The dodo may have been scorned, but its flesh was nonetheless cooked to fill the bellies of the Dutchmen.

The most influential of the island’s occupiers, the French, arrived in 1715. The colonizers turned Mauritius into a bastion of sugar. Rainforests were slashed and replaced by plantations. Cane thrived in the red volcanic soil. Now the governing elite and landowning class renamed the island Ile de France. They imbued the society with their language and culture. Most islanders today speak French, but Creole, a vernacular offshoot of the mother tongue, is the lingua franca.

To cut the cane, till the fields, and process the sugar, the French imported African slaves, mostly from Mozambique and Madagascar. Their descendants and those of mixed race are known as creoles.

Another European power, the British, set its sights on the sugar isle. In 1815, during the Napoleonic Wars, the French lost control of the island to the interlopers. Despite their defeat, the French continued to dominate the sugar industry and to maintain their Gallic culture and Catholic religion.

The English decision to abolish slavery and the slave trade in the early nineteenth century led to a radical change in the island’s population. Slaves began to abandon the plantations, creating a severe labor shortage. Sugar, the economic engine of the islands, required new hands. The English turned to their Indian colony for laborers. Just as would happen in Caribbean colonies like Trinidad, indentured workers were shipped in to replace the old workforce. The complexion of Mauritius changed as more than 300,000 Indians poured into the island between 1834 and 1910.

The Indians themselves were a polyglot group. Those from the South carried different traditions than those from the North. The new arrivals also spoke a mélange of languages—Tamil, Telegu, Hindi, Marathi. In addition, a significant number of the Asians, some 15%, were Muslims.

Over the years, many of the once disdained “coolies” lifted themselves up or elevated their children into higher status professional and commercial occupations. The Indian community acquired political clout. When the island gained independence in 1968, Mauritius’s first Prime Minister was Seewoosagur Ramgoolam.

Although a small portion of the population, another group of outsiders left their mark on the island. Attracted by economic opportunities, 7,000 Chinese immigrants arrived in Mauritius in just five years, between 1895 and 1900. Some became skilled workers, but the most important group were small businessmen. It was the Chinese who opened retail shops that catered to the Creoles in the small islands and villages. Speaking before the Colonial Assembly in 1885, Governor Sir John Pope-Hennessy argued that the entrepreneurs were indispensable: “We all know that at almost all the crossroads of the island are to be seen the well-built stone residences and shops of the Chinese that have sprung up within the last few years; and those Chinamen undoubtedly manage to sell the poorer classes of this community cheap and simple goods which the poor people wish to buy.”

Mostly bachelors in the beginning, the community, organized around clans, expanded with the arrival of family members. The ethnics have built pagodas, launched two daily newspapers, and popularized their culture among the islanders. As Chan Low, a local historian, told writer James Wan: “Chinese cultural events now see the participation of all kinds of Mauritians. If you go to Chinese shops, you find people of all communities buying Chinese food and goods, and even traditional practices, like the dragon dance, are performed by non-Chinese Mauritians alongside Sino-Mauritians.”

Melding such a mixture of cultures, ethnicities, and nationalities into one unified society has often been difficult. Relationships, for example, between Creoles and Indians have sometimes been tense. A common language, however, has helped create a common bond. Indians, whose forbears once spoke Bhojpuri may cling to their ancestral tongue but also communicate with the Chinese in Creole.

The varied strands of Mauritian culture have been woven together to form a national identify and a common cuisine. “We take it together and make it our own,” Toussaint points out. Different culinary traditions have been “creolized” in the island crucible. The boundaries between different kinds of food have broken down. Indian flavors seep into Creole food and vice versa.

Shrimp Rougaille at Aux Iles Bleues

First and foremost, there is the overarching sway of French cuisine, which has lent island cooking a sophistication and flair. The colonists brought metropolitan foods like cheese, wine, and pain maison. French cooking styles have also been remolded. The tomato-based sauce of Provence, for example, has been transformed. To the pomme d’amour, as the Mauritian tomato is known, has been added the bite of chili and the kick of ginger, garlic, and other spices. The classic Mauritian dishes served at Aux Îles Bleues, rougailles, are products of this marriage between French and Creole cooking. The word rougaille came into Creole via the French cooking term roux d’ail (a flour and fat roux infused with garlic).

As spices became more integral to Mauritian cooking, the taste buds of French islanders adapted. One nineteenth century writer, whom authors Jones and Andrews quote, remarks on the change: “They chew nutmeg and chilies as if they were sweets, and their pale features will hardly pink in the inferno of these condiments.”

Samosas at Les Delices de L’Ile Maurice

Indian words, slightly adapted, crept into the vocabulary of Mauritian food. Briani, Farata, samoosas, and the aforementioned vindaye are just a few examples of the borrowing. In addition to dishes of Indian origin like cari and khorma, basics of its kitchen like rice and dal (peas and lentils), have been assimilated into the culinary culture. Indian condiments turn up on the tables of other Mauritian ethnics. “Indian pickles are eaten with French dishes and, similarly, Chinese dishes are eaten with Tamil pickles and chutneys,” Madeleine and Clancy Philippe note in their cookbook, The Best of Mauritian Cuisine.

Indian cooking itself has undergone a metamorphosis. Caris [curries] may be less fiery and more delicate than their Indian counterparts. Mauritians “tried to make Indian food French,” Toussaint suggests. The ethnics have also acquired new tastes. Achard, the pickle-y relish, may sometimes be remade with palmistes or palm hearts. Octopus has joined the repertoire of Indian curries.

Chinese immigrants made their own contributions to island food. A new starch, noodles, caught on with locals; at Aux Îles Bleues, customers can choose between rice and noodles to accompany their main dishes. Mines Frite, stir-fried noodles, lost their ethnic associations and joined the national menu.

The Chinese played a key role as purveyors of Mauritian dishes. They were the first group to open restaurants, Toussaint points out. Chinese eateries, he says, serve up both Chinese and Mauritian offerings.

The Vegetable Soup with pineapple at Aux Iles Bleues

In all its variety, Mauritian cooking was coming into sharper focus. I continued to pick up revealing details about the food of this “cosmopolitan mix,” to use Toussaint’s image. For example, the vegetable soup with tart pineapple we were served at Aux Îles Bleues had puzzled us. Peggy and I wondered how it fit into Mauritian cuisine. In a later conversation, Toussaint explained. It was actually a sweet and sour soup inspired by Chinese tradition. There was still much more to explore on the menu. Maybe next time I’ll order the octopus cari.

NOTE: Two useful Mauritian cookbooks are:

• A Taste of Mauritius, by Paul Jones and Barry Andrews.

• The Best of Mauritian Cuisine, by Madeleine Philippe with Clancy Philippe.