From Middle East to Near East:

The Making of a Food Business

Part I

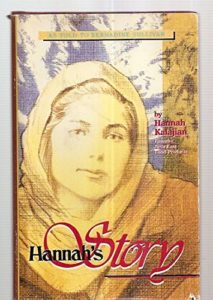

Cover, biography of Hernoush (Hannah)

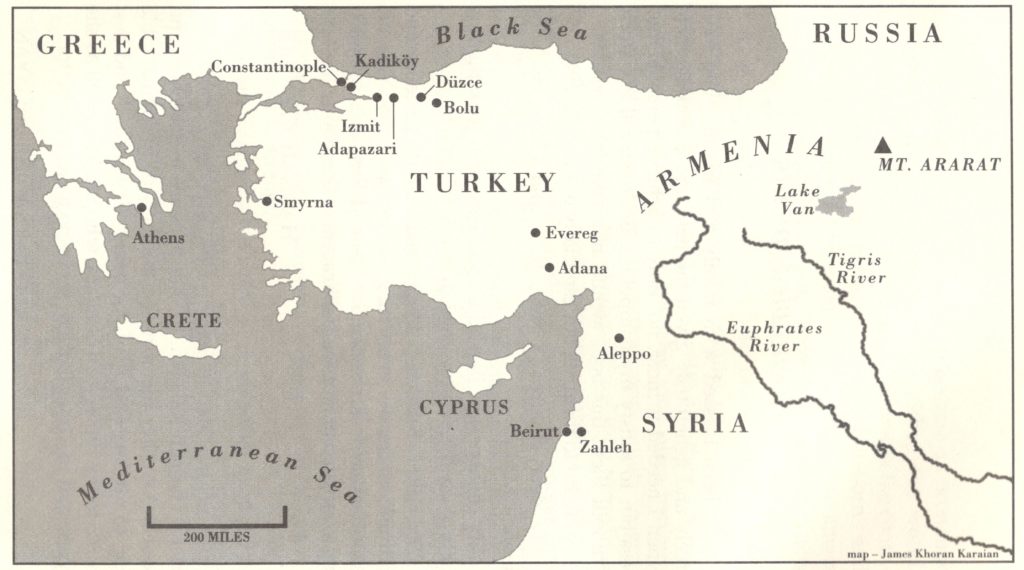

The ten-year-old Armenian girl has to flee from Duzce, a village close to Constantinople (now Istanbul), because of an imminent attack on her community by the country’s Turkish overlords. The “gendarmes,” her family is warned in 1920, have laid waste to a nearby village, “slashing, raping, robbing, and killing” Armenians. Heranoush Gartazoghian’s family and other fugitives must trek through the mountains to find a sanctuary. It is an ordeal of pain, hunger, and exhaustion. In Hannah’s memoir (the name she took in the U.S.), she recalls her mother’s struggle to keep her family’s spirits up. Once she pretends to cook a pot of pilaf over the fire: “ ‘Now the pilaf is cooking,’ she croons. ‘It will be ready soon! How good it will taste! Can you smell it?’ ” Hannah remembers sitting in “the cold ground, hugging our knees, hypnotized. I am sure I can smell the hot pilaf and see the glow of the flames.” (The autobiography is titled Hannah’s Story.)

Logo of Near East Food Products

The dream of making and eating pilaf will continue to animate her life. In 1962, Hannah founded Near East Food Products, which popularized packaged ingredients for rice pilaf, bulghur, couscous, tabbouleh, and many similar products in America. Very early, she displayed the qualities of courage, persistence, and ingenuity that would later serve her well. On her early, harsh journey, and on several others to follow, she was nothing if not indefatigable. Journalist Dolores Courtemanche, who interviewed Hannah in 1989, was impressed by how “dogged” the innovator was.

Born in 1910, Hannah is the fourth daughter of Mateos, a wealthy meat dealer, and Cohar, the daughter of a priest. The aromas of her childhood home permeate her memory: “I would dream of the good smells of home, the bulghur (cracked wheat kernels) cooking, the big iron pans of parag-hats (Armenian cracker bread) baking over the open fire, the apricots and raisins spread out to dry.” Along with the joys of growing up, she feels the animosity of the Turks, who call the Armenians giavors (heathens).

In 1915, after the breakout of war, Turkish soldiers come and grab her father and other Armenians. They are ordered to “serve” in the army. Mateos starves to death in an army labor camp. Her mother works in the tobacco fields to support the family. Hannah helps out cleaning, sewing, and preparing pilaf, which she carries out to her mother. The dish was made from scraps of wheat the workers gathered in the fields.

Five years after her father’s death, Hannah’s flight from her village is a hundred-mile slog through rugged terrain. After their grueling trip, the family finally reach Constantinople. Believing that their journey is over, Hannah exults: “Forgetting the journey, enraptured by the pointed spires, the minarets, the great Hagia Sophia and the Bosporous Bridge in the morning sun, I dart here and there like a wild rabbit.” But her joy is short-lived. Seeking sustenance for her daughter, Cohar places Hannah in an orphanage. During her confinement, Hannah extracts small pleasures, like learning how to make lace, but contracts pneumonia. Her mother takes her away to stay with her and Hannah gradually regains her health.

Map of Turkey a century ago

On the mend, Hannah one day explores the city’s bazaar. Looking back on the exhilarating experience, she thinks the spectacle awakened her commercial drive: “Ah, the shimmering jewels, the silken shawls, the bright carpets, the sweet shops, the baskets of figs and almonds! And oh, the smells . . . the shish kebab, dripping and sizzling over glowing coals! . . . I am so excited and happy that I have no idea whether or not the raisins and roasted chickpeas—the promised chamich lablabco—ever fill my pockets. . . . I want to own every shop I see. I hate to leave the excitement, the bartering, the jingling of coins, the cries of the vendors.”

There was little time to savor the pleasures of Constantinople. Reports of brutal attacks by the Turks on the religious minority in Smyrna, a town to the south, force the family to join the exodus of fellow ethnics from the city. The constant dangers finally convince the Gartazoghians to leave Turkey. They pack up again and, with a little bit of cash from a sister living in America, buy a ticket on a ship bound for Beirut. After a rocky voyage, they land in Lebanon and head to Zahleh, a dreary river town that would later blossom into a luxurious mountain resort.

Hannah adapts to Zahleh with her usual persistence and determination. She begins attending school and soon snags a job cleaning a new Protestant minister’s church. Hannah parlays the job into a position as a housekeeper for the cleric. Juggling all these tasks, she manages to continue her studies and even wins first prize in the school’s final examinations.

Ever the voyager, Hannah decides to embark on a new journey. Dikranouhi, her older sister in the U.S., begs and begs for Hannah to join her in New York City. To pay for her passage, she trades in her last piece of financial security, the gold necklace Dikranouhi had given her.

She sleeps on the deck of the boat that is bound for Piraeus, the port of Athens. After arriving, she wends her way to a train station and, clutching her burlap satchel, climbs aboard a train for Paris. From there, Hannah boards another train for the port of Calais to meet a ship that will take her on the long Atlantic passage to New York. The thirteen-year-old will never see her mother again. She is taken to third class quarters at the bottom of the vessel, where she begins a lonely, painful passage until she has a stroke of luck. A handsomely dressed Armenian woman befriends the seasick, famished young girl. She lets Hannah share her cabin for the rest of the trip. She is treated to hot water, showers, and a new white dress. The ship stops at Ellis Island, where passengers are subjected to stern inspections and puzzling questions (“Do you have glaucoma?”). Passing the test, Hannah returns to the ship, which sails up the Hudson River to its dock. Her sister greets her and the émigré embarks on a new leg of her journey.

Third Avenue El, New York City

They board the Third Avenue El to Dikranouhi’s apartment in the Bronx. Hannah takes on the family’s household chores, tending to the children, cooking meals, all the time attending classes in the “foreign” section of a nearby school. Her interest in cooking is stoked on visits to the Balkan Restaurant, a dining room in the “Little Armenia” section of Manhattan. Hannah’s cousin is married to the owner. She delights in the “fragrant smells, shining utensils, and constant motion.” Hannah “haunted” the restaurant, reporter Courtemanche writes, “always asking questions.”

Determined to cut the apron strings to her family, she finds a job as a “touch up” worker in a Harlem rug plant. The debilitating works leaves her back in pain and her hands sore. Abandoning the job, Hannah winds up in a training program, monogramming initials on napkins, tablecloths, and towels. Hannah moves on again for a slot on the assembly line at the National Biscuit Company plant on the New York waterfront.

Hannah soon wearies of this job, as well. A tempting Christmas position opens at Bloomingdale’s, the Manhattan department store. She signs her name “Hannah Reader” on the application (Gartazoghian means “one who reads”) and lands a job as a salesclerk. She thrives on the “chaos and intensity of the workplace.” Moving up the clerical ladder, she gets a job at Gimbel’s, where she is assigned to the “Men’s Underwear Department.”

Note: Hannah’s Story: Escape from Genocide in Turkey to Success in America, the book by Hannah Kalajian (as told to Bernadine Sullivan), 1990, was indispensable to my piece. JSD

[End of Part I]

Part II: Hannah gets married and builds a business.