Packaging Pilaf:

Hannah Kalajian and the Making of Near East Food

Part II

In Part I, Hannah Gartazoghian (later Hannah Kalajian), a ten-year-old Armenian girl, the founder of Near East Food, flees her village in Turkey. (Near East makes packaged rice pilaf, couscous, and other similar items.) She embarks on a harrowing journey that will take her to Constantinople, Beirut, and ultimately to the U.S. Part II picks up in the Bronx, where she has joined her sister.

After a five-year sojourn in the Bronx, Hanna turns 18 and finds love. She meets George Kalajian, the brother of her cousin’s husband. After a whirlwind courtship, in 1929, Hannah gets married in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where her partner lives.

Double wedding: George Kalajian marries Hannah (group on left) and his brother Mike marries Victoria (group on right)

George, who had also fled Turkey, comes from Evereg, the same small town where Hannah’s parents grew up. An edict posted in the community forced the departure of George’s family: “In three days your homes will be padlocked. You must leave this country and go to Syria.”

The young boy, about eight or nine, his mother, a sister, and three brothers, led by their father, a town merchant, take flight to escape a certain massacre. After reaching Damascus, which had been inundated with refugees, the clan decides to set out for Arabia—George’s father, sister, and his two younger brothers die during the desert trek.

A sheik takes the survivors, George and Mike, under his wing and puts them to work cleaning his stables and doing other menial jobs on the property. Considering him part of the family, the landowner offers George his daughter in marriage. The brothers finally escape his clutches, leaving in a caravan carrying goods to Damascus. After receiving money from a sister living in the U.S., they head for America and settle in with her in Cambridge.

Hannah moves to Cambridge to join George and assumes another burden, caring for his ailing sister. But her new home excites her: “Cambridge thrills me over and over. It offers quiet walks by the Charles River, the fragrant gardens, and ancient elms of Longfellow Park and the ivy-covered walls of Harvard buildings.” One day Hannah listens raptly to a lecture by Dr. Roger W. Babson, a Massachusetts entrepreneur and founder of Babson College, who extolled the opportunities offered in her adopted land: “America is a land where initiative is rewarded. Whoever can produce even a better shoelace can get rich in the United States.”

George and his brother Mike possessed the pluck Babson had praised. “Natural gamblers,” Hannah calls them. They purchase an ice cream spa in Waltham, a nearby town. But they made their gamble in 1929, when the collapse of the economy made it impossible to keep their business afloat. Two years later, the owner of the business returns from Italy and takes back the shop. Ever the optimist, George persuades his wife to return to New York City, where he starts work in a produce market making five dollars for a six-hour day. The grueling pace exhausts him.

Hannah Kalajian surrounded by family, Christmas 1945: George, son Jack and daughters Cohar and Carol

Seemingly out of options, the couple who now have two young children, Cohar and Hagop, decide again to pull up stakes. Hannah remains her tenacious self: “A familiar restlessness possesses me. There is something better out there than survival. If I could just recognize it, touch it, find the way.” George has a friend in Worcester, an industrial town west of Boston, who wants help managing his grocery store. Hannah marvels at this city of seven hills, many of whose dwellers live in triple-deckers, structures built for Worcester’s working class. The family settles into one of these houses. “In the back I can see three layers of back porches where laundry flaps on identical circular clothes reels,” Hannah reminisces.

George’s employer, however, goes bankrupt. The failure convinces Hannah that the couple must have their own business. They rent a former candy store, which they convert into a combination grocery, ice cream bar, and luncheonette. In 1941, they buy the building, whose upstairs becomes the family residence.

Worcester, which made corsets, dining cars, shredded wheat, and other products, had a long history of Armenian settlement. In 1905, the manufacturing city had the largest community in America of these immigrants. As historian Dr. Hagop Martin Deranian tells the story, when an Ellis Island official asked a newly arriving Armenian for his destination, he responded, “America.” Baffled, the agent told him he was already there. “No, no Worcester is America,” the Armenian said.

Protestant missionaries from New England, who took their message to Armenians in Turkey, sowed the seeds for their later migration to America. Kharpert Province, an area 900 miles east of Constantinople, was fertile ground for the ministers. Rev. George Dunmire, a campaigner whom historian Robert Mirak cites, was intoxicated by the opportunities provinces like Kharpert offered: “the richest country and the most inviting and promising missionary field I have seen in Turkey.” Many of Worcester’s Armenian settlers hailed from Kharpert, where in 1856, a Protestant Evangelical Church was established.

The first Armenian to make his way to Worcester was a young man, Caro, who came with Rev. George Knapp, a Congregational minister. Knapp employed him as a servant in his home. The pioneer was followed by an influx of young artisans and peasant farmers, mostly bachelors, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They took jobs in factories like the Harrison and Richardson Arms Company, the Winslow Skate Manufacturing Company, and the Crompton and Knowles Loom Works.

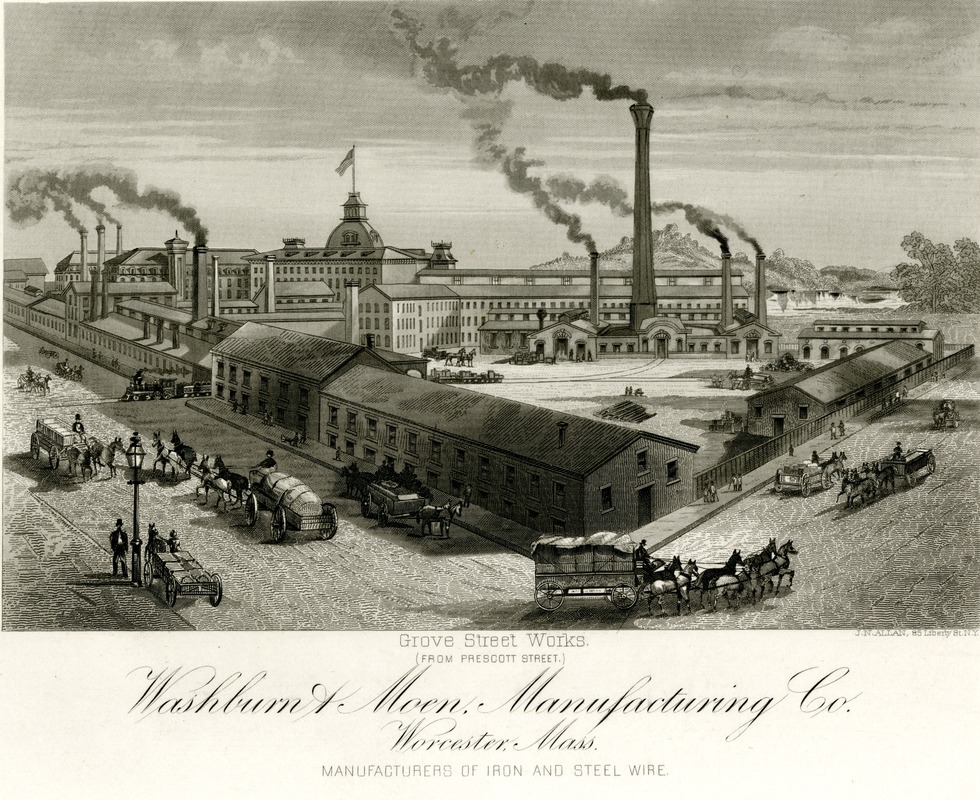

Washburn and Moen Manufacturing (The Wire Mill) in Worcester, Massachusetts

The Washburn and Moen Manufacturing Company, or the “wire mill” as it was commonly called, was a magnet for the immigrants. The mill, the town’s largest business, manufactured barbed wire for fences in the West, wire for pianos and electric lights, and other necessities. Owned by Philip Moen and Charles Washburn, who had strong ties to local missionary leaders, the company sought out cheap, hard-working hands. “Armenians will not work anywhere else,” the Worcester Telegram newspaper pointed out. By 1889, 300 Armenians were on the wire mill’s rolls.

Caro, the clergyman’s servant, was one of those tempted by the attractions of a factory job. As historian Deranian recounts it, an Irish laundress working for Rev. Knapp persuaded Caro that there was more money to be made in one of the city’s factories than as a servant. He left his domestic job and went to work in a mill, where he made $1.50 a day (versus his old pay of $0.75 a month). Caro wrote glowing letters to his countrymen encouraging them to follow his example.

The Armenian path in Worcester was not an easy one. The newcomers were frequently bullied, mugged, and, possibly worst of all, taunted as “Turks.” But the immigrants persisted and soldiered on. The respect in which they were held by many of their bosses also helped: “As a rule, [the Armenians] are temperate,” Charles S. Hall, a mill official, wrote a friend in 1889, according to historian Deranian. They “use no profane language—and do not use intoxicating liquors. As a rule Protestants … very peaceable and quiet, generally steady workers.”

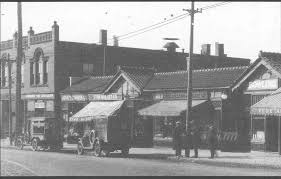

Original Star Market in Watertown, Massachusetts

The factory was a way station for many Armenians, who, impatient with the harsh regimen, desired a more independent life. They displayed a flair for entrepreneurship. Sarkis Mugar (originally Mugerdichian), who had been a tinsmith in Turkey, scholar Deranian notes, toiled as a young man in Worcester’s wire mills. In 1916, he acquired the Star Market, a grocery in Watertown, Massachusetts, for $900. The small store was the launching pad for the supermarket chain his family built.

In a large Armenian neighborhood in Worcester, the 1910 Census counted 73 wire workers, but also 15 business owners, 8 grocers, 8 tailors, 4 shoemakers, 2 doctors, and 2 dentists. The immigrants’ commercial drive, industrious habits, and other New England virtues won them praise. “It is no small thing to have a colony of these ‘Yankees of the East’ in our city,” Protestant minister Milan H. Hitchcock applauded in 1901. The Armenians generally, historian Mirak points out, surpassed many other ethnics in their achievements: “The Armenians adjusted to the American economy with a relatively high degree of success. Only the Eastern European Jewry adjusted more rapidly to America.”

Hannah and George Kalajian carry on the Armenian entrepreneurial tradition. Their shop gradually builds a clientele. Workers from the nearby lumberyard come by for coffee and doughnuts. Hannah expands her menu to include sandwiches and pies. The store sign now reads, “George’s Fruit Market and Luncheonette.”

Hannah begins turning out daily specials at the 12-stool lunch counter. “American-style” plates—”baked beans, chop suey, beef stew, macaroni and cheese”—cater to customer tastes. She decides to make roast chicken and Armenian pilaf to “lure” patrons away from “American carbohydrates.” Her customers become avid fans of the dish. Despite all the daily pressure, Hannah works hard at keeping her food heritage alive: “In the summer she’d gather young grape leaves for stuffing and in the spring she’d find wild greens for salads,” son Jack tells the Christian Science Monitor’s Phyllis Hanes. “She made phyllo dough from scratch for sweets with layers of flaky pastry spread with honey and butter and chopped nuts. She was always stuffing tomatoes and eggplant or rolling cabbage and grape leaves.”

A family emergency disrupts the shop’s steady momentum. George falls ill with pneumonia and is bedridden for almost two years. Hannah takes on all of the chores of the business, handling groceries, running the luncheonette, whipping up ice cream for school kids. She pays a price for the ordeal: “I didn’t know I was having a breakdown. I knew only that a captive demon gnawed at my insides but never quite escaped.”

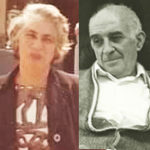

Hannah and George Kalajian

More obstacles confront the business. Lincoln Square, the hub of their trade, is slated to be demolished so that a tunnel can be built beneath it. The Sawyer Lumber Company, whose employees were Hannah’s most regular customers, moves away. Hannah fights exhaustion and, after a hospital stay, travels to California, where her son Jack and his family and other relatives live. She needs a respite from the daily toil: “I dream of a solution to this endless parade of hours behind the lunch counter, but I always wake up to a body still bone-tired and a mind too numb to plan.”

One day during her recuperation, Hannah has a revelation. At dinner at her cousin Missak’s (the owner of the Balkan Restaurant, an Armenian dining room in New York City), the guests are served the inevitable “steaming bowls of pilaf.” The oily noodles bother Hannah’s stomach. Missak suggests that toasting them in the oven might be preferable. That night, her imagination stimulated, Hannah begins musing: “I retire early, but can’t get to sleep. Something is boiling up inside my brain. It’s like a hot spring, bubbling closer and closer to the surface.” She leaps out of bed and tells Jack and his wife, Lorraine, of her dream. “I’m going to start a business! I’m going to put my pilaf on the market! My own pilaf mix!”

Husband George, who had experienced the severe demands of running a small business, was at first skeptical about the idea. “Dad said, I know the grocery business, and you can’t do that,” son Jack told Boston Globe correspondent Gail Perrin. But the commercial climate of the day emboldened Hannah. “In the markets, the big thing was packaged mixes,” she commented to a reporter. “If they can do it, so can I.”

Returning to Worcester, she has a head of steam. Leaving the lunchroom responsibilities to George, who has recovered, Hannah begins a tireless effort to create the right blend of flavor, spice, and texture for her product. The details, particularly what kind of noodles to use, pressed on her mind. After sampling a pilaf one evening at a buffet at the Church of Our Saviour, an Armenian church in Worcester, she decides to substitute orzo for vermicelli. “We find we can quick-fry the orzo, a wheat pasta shaped like small ovals, on top of the stove. The oil coats it, but it doesn’t sink in. And it stays crisp. . . . It’s still crisp on the shelf and nutty delicious.”

The problems of starting a small food business—shelf-life, standardizing the product, and finding wholesalers who can sell her everything from glue to spices—consume her. She immediately contacts the FDA. “They put me in touch with suppliers and told me what I could do and what I couldn’t do,” Hannah tells Worcester Telegram and Gazette correspondent Dolores Courtemanche. Hannah turns the family kitchen into a testing lab to resolve a host of questions: “How strong should our foil bags be? One pouch or two in each mix? What could go wrong with our dehydration techniques?”

A production line of family and friends, stretching from the living room to the kitchen, assembles pouches of ingredients, which were initially dried brown rice, Lipton chicken stock, and broken vermicelli noodles: “The bags march raggedly forward. Ingredients are carefully measured, knifed off clean from cup or spoon, and dropped in,” Hannah writes. “At the end of the line, the warm glue is spread and the sealed bags line up like soldiers, in a succession of trays.” Looking back, her daughter Carol recalls the makeshift system in an interview with Pandolfi: “It was a real Mickey Mouse operation. All these Armenian ladies working in that tiny room.”

Near East original rice pilaf box

Hannah calls her product, “Near East.” The package’s “exotically curved letters,” she observes, suggest “a hint of camels and desert sands.” A sheaf of wheat adorns the left side of the boxes. The business is formally established as Near East Food Products, Inc. in 1962 and begins selling both rice and wheat pilaf.

Getting grocery stores to buy the product was Hannah’s next big challenge. “Back then, pilaf was very foreign,” son Jack told journalist Mary Tuthill. “My mothers and sisters had to take bowls of pilaf to the stores to people could sample it and find out what it was.” Daughter Carol often carried an electric pot in the trunk of her car on sales trips. Interestingly enough, it was actually the family’s ethnic ties that helped the fledgling business break into the large Boston market. The Mugars, an Armenian family whose patriarch was the aforementioned Sarkis, agree to carry the pilaf in their supermarket chain, Star Markets. “We have a foothold,” Hannah enthuses.

The Star Market breakthrough opens new opportunities. Daughter Cohar capitalizes on the initial success. She “spent day after day spinning her wheels through the slush and ice of countless New England towns,” Hannah recalls. “It’s wonderful how doors open once you have ‘references’: ‘Yes, we’re doing very well in the Star Markets, you know….’” After that pitch, Cohar would set up a card table in the store and woo customers with the fragrant smell of pilaf wafting through the store.

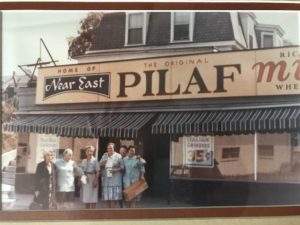

Hannah (left) with work crew in front of their grocery-luncheonette, where Near East Foods started

The “ragtag” production line bursts its confines and moves downstairs to the grocery. A new store sign announces the launching of the hybrid business: “Home of The Original Near East Pilaf Mix.” Before long, Near East signs up Gimbel’s, Gristedes supermarkets, S.S. Pierce, and even the Macy’s in New York City.

Near East begins turning a profit, grossing $200,000 in 1972. Son Jack, who is an engineer, designs a packaging machine that doubles the number of boxes the business could turn out. In 1977, the company establishes its own plant in Leominster, a town outside Worcester. Near East continuously adds new items to its line—tabbouleh, couscous, lentil pilaf, and Spanish rice. In the 1980s, sales soared and its products are now among the top ten best-selling supermarket items in the Boston area. The company also expands its reach, marketing to restaurant chains like Marriott, Howard Johnson’s and Red Lobster. Now a global business with sales in England, Canada, and Australia, Near East is purchased by the H.J. Heinz Company in 1986 and is now owned by Pepsico, which acquired it in 1993.

Hannah Kalajian, who died in 1990, was reinventing a Middle Eastern staple for the mass market. (George passed away in 1978.) Every village may have had “its own rice pilaf and each family in the village … its own rice pilaf using whatever was available,” as her son Jack explained to correspondent Dolores Perrin. But such fine distinctions did not deter this old world woman who quickly grasped the power of modern merchandising and packaging. She was determined to make a uniform product that had wide appeal.

It was strenuous enterprise in the American marketplace that produced success, Hannah believed. The gospel that “initiative is rewarded,” the mesmerizing words that she heard Dr. Roger W. Babson preach in Cambridge, was her creed.

Note: Hannah’s Story, Hannah Kalajian’s autobiography, was indispensable for this piece. Worcester is America, an excellent history of Armenians in the Massachusetts city, by Dr. Hagop Martin Deranian, was a vital source.