“From Pushcart to Posh” — An Appreciation by Joel Denker

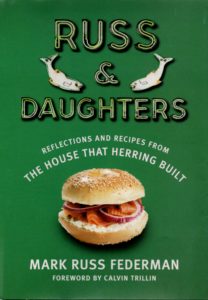

Russ & Daughters: Reflections and Recipes

from the House that Herring Built

By Mark Russ Federman

“I need a whitefish … It should be a nice one … My son, the doctor, is coming over for dinner… We want to introduce him to a nice girl … Her family is very well situated, thank you … Her father’s a big shot … Maybe this will work out, please God, and I’ll soon be a grandmother … No, don’t give me that one from the top. What do I look like? A greenhorn? I want from underneath. No, not that one. The one next to it. No, that one’s too dried out. You probably had that one left over from before the Flood … Why don’t you go to the back and get me a fresh one?”

Mark Russ Federman, whose grandfather Joel Russ founded Russ & Daughters, the temple to Jewish delicacies and other treats on the Lower East Side, tells this story, a composite of customers he encountered at his shop, as recounted in his book, Russ & Daughters: Reflections and Recipes from the House that Herring Built. The business lures customers with a wide array of products, from herrings, lox, sturgeon, sable, whitefish, and scrumptious salads, to dried fruits, nuts, and traditional sweets like babka, rugelach, and halvah. It has, over the years, introduced candied ginger, apricots, and orange peels as well as Turkish figs, Syrian dates, and Persian pistachios to its display.

Federman ran the store for 30 years (the third generation owner has passed the baton to his daughter Niki and nephew Josh). Federman, who has a gift for humor and gab, is a superb storyteller. His book, which has not received the recognition it deserved, is at once a full-scale portrait of a lively family and a chronicle of the evolution of an ethnic business. As a writer myself, one who has spent several decades trying to unearth similar tales, I was captivated by it. Russ & Daughters is a singular contribution to the history of ethnic food in America. The spicy details Federman offers up along the way make it even more delectable.

The saga of Joel Russ, the store’s patriarch, which Mark tells with vivid and enticing anecdotes, is a unique, but also a profoundly American one. He tells the story of his grandfather’s journey from the Jewish shtetl in Strzyov, part of an area called Galicia (in today’s southeastern Poland). His village was desperately poor, and growing up there was something Joel rarely spoke of. The 21-year-old arrived at Ellis Island on January 19, 1907, where the officials listed his occupation as apprentice baker. Joel had come to help out his oldest sister, Channah, who operated a herring stand with her husband on Hester Street in the Lower East Side. Taken from wooden barrels and wrapped in newspapers—typically The Forverts (Forward) or Der Tog (the Day)—the briny fish was sold to shoppers.

Herring was the mainstay of an important meal: “A poor immigrant would take home and unwrap the herring, put it in a cast-iron skillet with some sliced potatoes and onions, and then cook the dish in a coal-fired stove. With thick slices of black bread or rye or leftover Sabbath challah, this was a meal for an entire family.”

Street Peddler on the Lower East Side, New York

Joel moved up and acquired a pushcart—he later drove a horse and wagon. In the meantime, he had seen a matchmaker, who introduced him to his future wife, Bella Spier, also from his Galician homeland. Joel’s next steppingstone was a candy store, a cheap investment for many enterprising newcomers. A few years later, he established Russ’s Cut Rate Appetizing on Orchard Street. This shop was the parent of today’s more modern and sophisticated Russ & Daughters on Houston Street (he enlisted his daughters in running the business). The store is located today at 179 East Houston Street.

Near his old shop were a host of vibrant ethnic enterprises. A dairy store sold farmer’s cheese, ladled out milk, and vended tub butter. A deli made pastrami, corned beef, and tongue sandwiches, as well as hot dogs. Seltzer, which could be infused with different flavored syrups, was on offer at a local candy store. A mushroom store, next to the candy shop, sold a very popular item that was largely used for soups.

This book is full of tantalizing vignettes and anecdotes, but what stands out are some broad, universal themes in the immigrant experience. One is the toil it took Joel and his clan to build this business. For Joel, who worked uncomplainingly through the drudgery, this venture was only a pathway to what he hoped would be his final destination. His burning ambition was to get out of the teeming, dirty Lower East Side for less cramped spaces to stretch his elbows. Russ never idealized his neighborhood. During the 1930s, the Galician joined with other Lower East Side businessmen in a campaign to drive pushcarts out of the neighborhood. Ironically, although Joel was ultimately able to move his home outside of the Lower East Side, he was forced to keep his business there.

The appetizing store, Federman keenly observes, was an American invention that drew on Jewish tradition. These early shops, which inspired many a Sunday brunch, had no counterparts in Eastern Europe. There, pike and carp were bought for the Sabbath and salt herring sustained the weekdays. Russ and others carried new fish, unavailable in the Old World, like whitefish, sable, and salmon. These and other fish could supplement the old standby, herring.

Another motif that runs through immigrant history is what Federman called the transformation “from pushcart to posh.” Federman’s tale of how Russ & Daughters adapted to a changing neighborhood, where Lansky’s Lounge replaced Ratner’s Dairy Restaurant, where condominiums sprouted and “media consultants, graphic and fashion designers, computer experts, and bankers” settled, is brilliant. The owner had predicted this change: “Sooner or later, uptown will move downtown.” Federman, who had once been an attorney, was determined to maintain the older sensibility without stubbornly rejecting all change.

Customers’ tastes were changing: “I would look up from slicing lox and see a well-heeled, well-educated crowd of younger shoppers. Expensive baby strollers replaced old wire shopping carts. These customers didn’t buy many hard candies, but they did purchase fancy hand-dipped chocolates. And along with cream cheese, they also wanted sheep-and-goat-milk cheeses to accompany their smoked salmon.”

Product changes are recurrent ones in the ethnic food business. Charlie Sahadi, who runs Sahadi’s, the large Middle Eastern food emporium on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, once explained to me the necessity of marrying ethnic wares with “specialty foods.” He teased his shoppers with both olives and low-fat McCann’s Irish oatmeal.

The “etzel-petzel” (seat of the pants) operation was also modernized and streamlined. When Mark’s daughter Niki joined the business, she took responsibility for “special projects” in a store that was acquiring not only national recognition but global reach.

Federman views his role as not only purveying fish but also merchandising “nostalgia.” He means nostalgia in the best sense of the word, as a longing for the richness of the past. The late Israel Shenker, who wrote for The New York Times, had a similar take on the allure of Jewish food. He called it “the heartburn of nostalgia.”

When I think back about the book, it’s the tiny, telling details that I recall. There’s the old-fashioned apple corer-peeler displayed in front of the store, which is still used to prepare apples for chopped herring salad. Federman is also at his best evoking the sensory experience of Russ & Daughters: “Push open the door at Russ & Daughters and the first thing to hit you is the store’s unique aroma. It’s a combination of smokiness from whitefish, salmon, sturgeon, and sable; the brininess of herrings and pickles; the yeastiness of freshly baked bagels and bialys; and the sweetness of rugelach, babka, chocolates, and halvah. How I wish I could bottle that singular scent—smoky, briny, yeasty, and sweet.”

For more about the history of Jewish food in America, see Chapter 5 of my book, The World on a Plate: A Tour through the History of America’s Ethnic Cuisine.