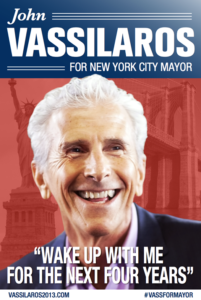

Campaign Poster for Vassilaros for Mayor

“The Right Man, The Right Coffee.” An unconventional campaign slogan in the New York City race for Mayor in 2013. John Vassilaros, the third-generation Greek American to lead the family business, was the standard bearer. Posters, a web site, videos, and social media heralded his run. “Wake up with us for the next four years,” one poster declared. Founded in 1918, Vassilaros & Sons Coffee Company’s product became a staple of many Greek-owned diners and coffee shops, but its name was largely unknown.

To broaden its audience, to reach consumers directly, Johnny, as he was affectionately known, hired an advertising agency to orchestrate the mock campaign. The goal of the publicity was to identify the product more closely with its home town. Other earlier brands, like Chock Full o’ Nuts and Savarin, had marketed themselves that way. The panel on company trucks would read “NYC Dept. of Coffee.” “Vassilaros & Sons needs to own ‘New York City Coffee … there isn’t a brand identified as the city’s own,’ advertising executive Richard Kirshenbaum commented to The New York Times.

Salesman JJ Papalas Stands Next to Vassilaros Coffee Truck

Mr. Vassilaros enlisted a friend, the comedian Lewis Black, to help in the promotion. The comic praised the brand as “the finest cup of coffee ever served in the city of New York.” Black, the joke went, did two video takes, one on caffeine, the other not. The campaign let its audience in on the truth behind its whimsical strategy: “Unfortunately, Johnny Vassilaros has decided not to run for New York City’s mayor,” the web site said. “He is too busy running New York City’s best coffee company.”

The founder of the company, John’s grandfather John Anthony Vassilaros, arrived in New York City as a young man, with his wife and young child, penniless, from Ikaria, the rocky Greek island in the Aegean Sea. Looking back, Alexandra Vassilaros, the wife of his grandson, remarked to an interviewer from EdibleLongIsland.com, “He left to mine possibilities in America. He was a true immigrant seeking a better life. He was very dynamic and entrepreneurial.” To put food on the table, he took two jobs as a waiter, a lunch shift on Wall Street and a dinner one in the Bronx. In his spare time, Vassilaros, who had no formal education, spent time at the New York Public Library struggling to learn English. He moved on to work as a salesman for a Greek-owned coffee company, but the restless young man bridled at laboring for someone else.

Map Showing Greek Island of Ikaria in Red

Convinced that he could produce a better product, John, his wife Sofia, and his sister Frosini got to work. They roasted beans in their kitchen and gradually improvised their own blend. Carrying 40-pound bags of coffee on the subway, he and Sofia set out to sign up customers. His personal touch when visiting restaurants was a key to John’s success. “He used to hand out cigars to all the dishwashers, thinking that one day all these guys are going to own all of their own businesses, and I’m going to supply them coffee,” Alexandra related in the interview. He soon opened his own storefront business and the enterprise took off.

The family patriarch cut a distinguished figure. He was a dapper man, granddaughter Ann Vassilaros told Estiator, a Greek food trade publication. The merchant was “larger than life; always well dressed with a carnation in his lapel.”

Tin Sign Promoting Vassilaros Coffee

Vassilaros spotted an opening in the market for his coffee. Greek immigrants would soon be operating an increasing share of New York’s lunchrooms and other small eateries. Winning them over, he calculated, would be crucial to the success of his product. He began loaning money and coffee equipment to help existing and aspiring owners get on their feet. The businesses he assisted would naturally carry his brand. Many of the restaurants remained reliable customers for decades. “He was probably the cornerstone of the diner business,” his great granddaughter Stefanie Kasselakis Kyles told Aaron Elstein, a reporter for Crain’s New York Business.

The restaurant patron forged personal ties with his client’s families. Known affectionately as the “godfather” of the Greek diner industry, he was literally one to their owners’ children. So many children received his baptismal blessing, the story goes, that a trip from New York to Florida took six months: Stops had to be scheduled to tend to his flock.

The Vassilaros home became a place to nurture “relationships,” an important word in the family’s vocabulary. John’s wife and relatives prepared Sunday dinners to entertain his followers. “If you have an open house on Sunday, they cannot owe you money on Monday,” was her great grandfather’s precept, Stefanie observed in an interview with the National Herald, a paper aimed at the Greek community.

The First Vassilaros Storefront in NYC

Ethnic ties bolstered the new enterprise. John sponsored newcomers from Greece, Erin Meister, the author of New York City Coffee: A Caffeinated History,

noted. Company employees took pride in their birthplace. “Our families

are from Ikaria,” former salesman John Joseph Papalas introduced himself

and his partner Gianni Pastis to the Queens Gazette. Mr.

Vassilaros was the founder of the Pan-Icarian Brotherhood, a society of

islanders from his homeland. The first Icarian clubhouse in New York

City was located in the 3rd Avenue building that the company owned.

Generous philanthropists, the family donated money to benefit their

Ikarian compatriots. Their donations built the island’s first hospital.

These connections were good for business. In an interview with the Queens Gazette,

writer Catherine Tsounis explained why her father, a Queens

luncheonette owner, was loyal to the Vassilaros brand: “I use Vassilaros

coffee from my patrioti John.” George Vlassios Tsounis hailed from Lemnos, an island close to Ikaria.

New York’s Greek-Owned Lexington Candy Shop Serves Vassilaros Coffee

John’s son, Adonis, expanded the family coffee business. Its headquarters moved to Queens, a large multi-ethnic borough with a sizable Greek community. Vassilaros started churning out coffee from a modern roasting plant, 25,000 square feet. Adonis carried on the firm with the same no-nonsense attitude as his father did. His attraction to the business was simple, Stefanie Kasselakis Kyles put it in the National Herald interview. “There are thousands of restaurants in New York,” she remembered him saying. “If you think of something to sell them for a few hundred dollars a week, you’re going to make a lot of money.”

John, the “mayoral candidate,” took the reins of the company from his father in 1972. The third generation president was a forceful, innovative leader and one with a winning personality. He almost effortlessly courted potential customers. “I’ve been a salesman all my life,” he remarked to Sara Costello from The New York Times. His technique—walk behind the counter and brew the coffee for his prospective client to sample. “The trick to selling is don’t talk too much. . . . Just let them taste it.” “Johnny” didn’t idolize coffee, as was increasingly the fashion. “Everyone’s so serious about the pour,” he told Costello. “Save your money and put down a payment on a house.” In the same spirit, his buddy, comedian Black, praised Vassilaros’ drink as “not a hipster’s cup of coffee.”

John was not afraid to visit competitors and strike up conversations. He did just that with Donald Schoenholt, president of Gillies Coffee Company, the country’s oldest roaster and wholesaler operating today. The businessman became an admirer. During his “campaign,” Schoenholt called John and promised his vote. The candidate thanked him and reminded Donald that he lived in Nassau County, Long Island, not New York City.

Mr. Schoenholt, the first president of the Specialty Coffee Association of America and a keen observer of New York’s coffee landscape, marveled at the visible signs of the Vassilaros success story. He envied its fleet of 15-16 trucks plying their sales routes. The Vassilaros roasting operation impressed him. Throughout the city, he said, lunch carts all seemed to be vending Vassilaros coffee, a tribute to the helping hand the veteran business had extended them. Johnny, Donald felt, lived and breathed his product. He had “ground coffee under his fingernails.”

Bags of Vassilaros Coffee

New waves of immigrants revitalized the Greek food business, bringing in potential new recruits. The lifting of government restrictions on immigration opened the door to 70,000 Greeks between 1945 and 1965. Some arrived in unconventional ways. Over 80,000 jumped ship in American ports between 1957 and 1974, sociologist Charles Moskos notes. When the newcomers took the helm of New York City’s diners and coffee shops (kind of mini-diners), Vassilaros’ early foothold in the industry gave the company an advantage in selling its product.

Risk takers, like Peter Zanikos, a fisherman’s son from the island of Kyos, typified the new breed of diner operators. He started as a seaman making $30 a month. “As soon as the boat comes to America, I jump off,” he said in One on Every Corner, a film directed by Doreen Moses and Andrea Hull. “I jump off like crazy.” In the early 1960s, he took a job washing dishes and ultimately saved enough money to buy his own coffee shop. From this building block, he assembled the Argo restaurant group, which at its peak consisted of 12 shops. For Zanikos, establishing a restaurant was a matter of pride: “So I told my wife. You’re going to help me. I want to be somebody. I’m tired to be poor.” Through the new immigration law, he sponsored his mother, sister, and two brothers “from the other side.” He installed his kin in the businesses and crowed about his achievement. “These people 90 percent is here because of me.”

From lunch carts and hot dog stands, the immigrants climbed the ladder to short order grills and luncheonettes. From “starter diners,” Harold Kullman, a New Jersey diner builder pointed out, they graduated to larger, more spacious establishments. In their heyday, diners were an irresistible bargain, Kullman observed. “When I started, diners were sold by the running foot, like boats,” he told journalist Peter Genovese. “For sixteen thousand dollars, you could buy a diner.”

The success of Greek immigrants in the diner trade was contagious. New arrivals were eager to follow their example. Owners provided jobs to friends and relations. Lowly dining jobs, as dishwashers and countermen, were stepping stones to better paying positions. “I can’t tell you the number of times the dishwasher ends up owning the place,” diner consultant Richard Gutman remarked.

The eateries catered to American tastes while downplaying the owners’ ethnic heritage. Moussaka, Greek salad, and rice pudding might be on the menu, but the mainstays were comfort foods like meat loaf, Salisbury steak, and liver and onions. “Where else do you go to get mashed potatoes and gravy?” asks George Vallianos, who ran the Elgin Diner in Camden, New Jersey. Over time, diners concocted more extensive, almost encyclopedic, multipage menus ranging from abundant breakfast items to pasta and seafood. No dish was too unusual for a diner to carry. “If you wanted to order an elephant,” coffee merchant Schoenholt quipped, “you could get it.” Always willing to oblige, operators were attuned to the changing favorites of their clientele. Blintzes might be included to appeal to Jewish regulars, or grits for Black customers homesick for Southern pleasures. Danny Pappas, a diner operator whose 14-page menu listed Irish sausages, Romanian tenderloin, Hawaiian chicken, and German potato salad among its 439 offerings, summed up the diner strategy: “We Greeks believe in volume. If somebody wants something, we don’t want to send them away,” he told The New York Times’ John Tierney.

Greek diners and coffee shops endeared themselves to the American public. A diner get together was a regular feature of the Seinfeld television show. The familiar clatter, rapid-fire order taking, and the wise cracking banter of these joints was parodied in popular culture. The Greek counterman’s patter—“Cheezborga, cheezborga, no Coke, Pepsi”—was featured on Saturday Night Live. The skit had updated an older lunch room chant, “Stamberry pie, peacha pie, happula pie, pinehappula pie,” in Chicago novelist Harry Petrakis’ rendition.

Celebration of 100 Years of Vassilaros & Sons Operation

A network of suppliers fed off the diner business. Wholesalers, many Greeks themselves, supplied the shops with baked goods, fish, paper products, and such vital accessories as the “show off” cases for displaying desserts. Like Vassilaros, these businesses were more than willing to lend the diners a hand. In the film by Doreen Moses and Andrea Hull, Marcos Kalogeros, owner of the Astro restaurant, reminisces about how wholesalers eased his way: “You go to the coffee man, he loan you 5,000 . . . the jukebox 5,000. You go put 1,000 down and you have your own restaurant.”

Vassilaros had hitched its fortunes to a booming market that is now eroding. The company’s major customers, diners and coffee shops, have been losing ground. Rents and operating costs are skyrocketing. Franchises like Dunkin’ Donuts are stealing customers. More and more, they were having trouble attracting a clientele with their something-for-everybody formula. “Halfway between fine dining and fast food,” reporter Aaron Elstein suggests, the diner didn’t fit neatly into an increasingly variegated industry. Customers were also searching for lighter, healthier repasts. Equally important, operators who were aging had no obvious successors. “The next generation has opportunities their parents and grandparents didn’t have,” Stefanie Kasselakis Kyles explained to Elstein.

Vassilaros & Sons, which had billed its brand as the everyday New Yorker’s cup of coffee, was now competing with purveyors of “specialty” products. Consumers were enticed by the tempting array of distinctive varieties available, coffee authority Meister points out. The new product was “not just coffee but something that was differentiated.” Its grade, unique aroma, national origin, and “free trade” commitment were now selling points. Vassilaros, an “ethnic-oriented” enterprise, as Schoenholt describes it, would have to break into unfamiliar terrain. His own company targeted “boutique hotels, specialty food stores, and white table cloth restaurants,” along with other select clients.

Vassilaros chief Stefanie Kasselakis Kyles closely followed these trends. A lawyer with a career in investment banking, Ms. Kyles took on a leadership role in the company after her Uncle John’s death in 2015. While acknowledging to the National Herald that “the Greek community was still a sentimental part of our business,” she was urging her firm to court more discerning customers. “Now there is a new appreciation for the bean,” the executive said in a web site interview. Savvy shoppers looked for “premium,” “quality,” “fine cup,” and “locally sourced brands.” John Moore, Vassilaros’s chief executive, echoed her views in an interview with EdibleLongIsland.com. “Millions of cups of coffee are consumed in the New York region, and yet barely anyone knows they’re drinking our coffee.” Besides “celebrating our past,” he emphasized the importance of “also looking to the future and changing how we look at the marketplace.”

A dilemma confronted the venerable coffee business. How can a company whose success was built on marketing a humble, anonymous product to diners refashion itself? Can Vassilaros acquire cachet and still retain its prized authenticity?