Greeks Celebrate in Melbourne’s Australia Day Parade

The cafés in Australia were not serving gyros or tzatziki. In their heyday, between the mid-1930s and the late 1960s, they resembled the diners, coffee shops, and quick lunch places Greek immigrants established in the U.S. The Greek-owned eateries courted customers with steak and eggs and milk shakes. In the city or countryside, these gathering places offered up hospitality and familiar food.

Outsiders, Greeks and other Southern European newcomers, descended on a predominantly English culture. Their presence was jarring to locals, who were predominantly British. Australians remained British subjects until 1949 and fervently sang “God Save the Queen.” Along with the U.S., Australia was a favorite refuge for the Greeks. (Melbourne today boasts the largest Greek-speaking population outside Greece.) The immigrants had a proclivity for self-employment, especially in the food business—85% of first-generation Greeks, demographer Charles Price notes, landed in the catering trade, either as owners or employees.

The first significant wave of Greeks arrived in Australia during the Gold Rush, often jumping ship, just as many immigrants to America from their homeland did. In addition to mining, they worked as cane cutters, tobacco farmers, factory hands, and in other low-paying employment. The “Golden Greeks” of the 1850s-1890s soon tired of the “diggings” and looked for more entrepreneurial vocations. They opened stores, taverns, and small hotels to serve the miners. Driving through the minefields in horse and wagon, some hawked provisions.

Map of Greece, with Island of Kythera at Bottom

By the 1870s, more voyagers from Greece were venturing to Australia. Many of them hailed from the island of Kythera, located between Crete and the southern tip of the Peloponnesus. For shepherds, farmers, and other young men struggling to eke out a living in this rugged land, Australia’s vibrant economy made it a magnet.

Athanasios Comino was one such wayfarer in search of a better chance. The son of a farmer, the Kytherian worked on a ship that in 1873 docked in Sydney. After injuring himself in a mining job, he began looking for another opportunity. After stopping to watch a Welsh shopkeeper dropping fish into boiling fat, the story goes, he imagined himself plying the same trade. Five years after arriving, he opened Sydney’s first Greek-owned fish business.

His success was contagious and other Greeks, many also from Kythera, took up the same trade. By 1911, 70 percent of the 400 Kytherians in New South Wales owned or worked in Sydney oyster shops, scholar Toni Risson reports. Their shops were modeled on the British oyster saloons or parlors, which served beer and shellfish to largely male punters. In the beginning, the unseasoned merchants stumbled while learning the ropes. For an order of fried oysters, it is said, Comino’s shop served them still in their shells. Although oysters, fresh, fried, or bottled, were their main fare, the Greeks added fruit and candy to lure customers. Restless salesmen, they were already eager to expand their commercial horizons.

Comino’s Cafe in Brisbane

For fledgling eateries with little capital, oysters—cheap and abundant in Australia—were a tempting product. In the 1890s, they sold for six pence a dozen. “In island towns, you could get fresh Sydney rock oysters,” historian Risson writes. “I believe it was the job of porters along the rail line to keep them wet.” Farming their own oysters, the Comino brothers expanded their mini empire. The immigrants had found a niche. “If there is a single word which summarized the lives of most Greeks in Australia early in the 20th Century, it is shop keeping,” historian Hugh Gilchrist points out.

The success of the “oyster kings,” as Athanasios and his brother Ioannis were dubbed, turned Comino into a brand name. Newcomers adopted it for their business, even if they were not kin. The brothers sponsored other islanders to join their employ. As they gained experience, the recruits often left to build their own enterprises.

The hired hands were mostly young and single. Their families in Kythera pushed them out of their nests to seek their livelihoods abroad. Their destination was typically a kinsman’s shop, where they might board in an upstairs room. In an interview with writers Effy Alexakis and Leonard Janiszewski, Anthony Flaskas recalled a typical migrant story: “The old people [my parents on Kythera] … they were very, very poor…. They pick Australia…. It was a new country and you had more chances. Came with six boys and an old man in [acting as chaperone on the way out]…. I’d never been outside Kythera…. Well, the old man [my father] he sent me here and I had to obey…. He mortgaged his home [to pay for my passage.]”

In order to get ahead, the prospects had to suffer through an arduous and cruel regime. One café worker, Panayiotis Aronis, who spoke no English, arrived In Sydney with three gold sovereigns in his pocket. His brother took the 15-year-old on in his fish shop. Panayiotis “worked from 7:00 a.m. to midnight, six days a week, and on Sundays, when the shop closed, he would scrub the floors and clean the furniture until 3:00 p.m., when he would take his lunch and fall into bed,” historian Gilchrist recounts. “In the evenings, all would be peaceful until 11 o’clock, when the hotels closed and the drunks came in; some louts would put salt in the sugar or refuse to pay for meals, and there would be angry arguments and sometimes damage to the shops.” Panayiotis spoke of his hardship: “We were slaves.” Looking back, he had mellowed. “I began to forget my troubled past and took Australia to my heart, determined to make it my own country and that of my descendants.”

Manual for newly arrived Greeks, entitled “Life in Australia”

A primer for greenhorns financed by John Comino, Life in Australia, advised immigrants on the hurdles they would face. The handbook, ten thousand copies of which were distributed free throughout Greece, warned of rosy hopes that dinner will “fall ready-cooked out of the sky.” It also cautioned, according to one summary, “even to think of migrating without understanding the need for hard work, willpower and persistence was ‘an act of suicide.’” Special care should also be taken not to offend their hosts: “Raising your voice, banging your hand on the table, making gestures, forming groups in the streets, impertinence, scruffy dress are, for the Australians, something strange and unattractive. Such habits are disliked and, anyway, belong to uncivilized peoples.”

From oyster saloons and fish shops, the immigrants moved on to the café business. Cafés serving basic meals spread out throughout the country. Open from early morning to late in the evening, they featured hearty, unadorned, and inexpensive food that catered to Australian tastes. The mixed grill, a stick-to-the-ribs meaty affair—steak, lamb chops, sausages, bacon, two fried eggs, and a grilled tomato—was a café fixture. The “old country tucker” included such items as roast chicken, Irish stew, meat pies, pork fillet, and toasted sandwiches.

Starting in the cities, the eateries spread out to country towns. Word-of-mouth advice from fellow countrymen about opportunities in new places enticed owners to pull up stakes. Gossip in the kaffenia, Greek coffee houses, was a fertile source of tips. Railroad lines pushed into the Australian interior and the entrepreneurs followed them.

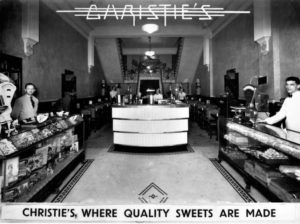

Christie’s Milk Bar, Brisbane

Country cafés were a haven for farm families visiting town for a shopping expedition or for a respite from the daily grind. In a hard-bitten society, they offered a convivial oasis. There were few other outlets in these communities for those in search of a convenient, filling meal. In a conversation with authors Alexakis and Janiszewski, historian Mervyn Campbell captures their vital role: “Many a time you would have gone hungry at night if it hadn’t been for a Greek café. You’d get into a country town after the hotel or dining room had closed and you’d have nowhere to go for a meal. But there was always a Greek ready to serve you a mixed grill…. They’d be open in country towns at seven o’clock in the morning and closing at midnight…. You could have a feed and meet your mates or take your girl for a date.”

The Greeks, a gregarious people, changed the dining culture of Australia. The eating places were imbued with the social atmosphere distinctive to their country’s tavernas. Their cafés “welcomed families from all social strata,” Alexakis and Janiszewski point out: “In Australia, nineteenth century public eating houses were ‘generally’ exclusive, divisions occurring along socio-economic class and/or gender lines—there were well-to-do restaurants usually providing French cuisine, frequented by middle- and upper-class patrons, or drinking and eating establishments with a male working-class clientele.”

For all the affection their patrons offered them, the owners still suffered ethnic taunts. They were tarred as “dagoes.” His family, who owned a café, were called “greasy spoon dagoes,” Peter Veneris recalls. On some non-Greek restaurants, historian Risson points out, signs said, “Shop here before the Day Goes.” To avoid being ostracized, owners sometimes put up posters proclaiming that they were “British subjects.” Although many chose Greek names for their businesses, others were more wary. Cafés were called Britannia, Royal, Empire, and Regal. Greeks also anglicized their names. One merchant, Ioannis Varipatis, became Jack Patty. Customers had nothing to fear from their cafés, owners proclaimed. They promised “cleanliness, civility, quick service.”

Antagonism might explode in violent attacks on foreigners. During the Depression, two days of riots on June 29 and June 30, 1934, targeted Greek-owned cafés, hotels, and homes. Officials gave their blessing to the popular suspicion of the immigrants. In 1928, the Prime Minister of West Australia tagged the Greeks as “that fish and chips crowd.” The immigrants were victims of what the government unapologetically called the “White Australia Policy.”

The Niagara Cafe in Gundagai

The hostility spurred the Greeks to embark on the commercial path to success. Shut out of other occupations, they turned to restaurant jobs. “Oh no, Greeks were certainly not allowed to work in factories—you had to work in cafés as cooks or waiters,” Angelo Raftos, who took a job in his uncle’s Sydney café, remarked.

The racial animosity encouraged the newcomers to huddle together, even more than they might have otherwise. The proprietor and his family lived a compartmentalized existence. There was the world of the shop, the long hours spent bowing to the needs and sometimes the whims of their customers. But at home, Greeks managed to create an alternative space of traditional pleasures and entertainment to revel in. Lex Marinos, whose family ran a café in Sydney, described their hidden life to Alexakis and Janiszewski. On Sunday nights, families would gather for jubilant evening at one of their cafés.

“The tables would be pushed back to create some space for dancing. A gramophone would materialize as would a collection of 78s…. Bouncy pop songs and mournful Rembetika [Greek blues]. Komboloi (worry beads) would spin back and forth around chunky fingers. Cards and backgammon….

“And then there was the food. Lamb baked with garlic and oregano. Cabbage rolls. Spinach and beans in olive oil and lemon juice. Fetta. Yoghurt. Rice. Pasta. Sticky sweets. Sugar-coated almonds.”

Because of their fears of rejection, café owners hesitated to share Greek dishes with their customers until the late 1960s and ’70s. “We sold steak and eggs and mixed grills, but never Greek food,” merchant Angelo Pippos remarked. “I tried introducing Greek food a couple of times but people didn’t like it.” Their cuisine, Alexakis and Janiszewski observed, was regarded as “foreign” and as “peasant” food. “Greeks have been eating their own behind closed doors since the 1850s.”

The Anglicized Greek café was refashioned with materials from American popular culture. A new hybrid, a marriage of mixed grills and milk shakes, was born. The Greek businesses, even the oyster saloons, installed soda fountains and ice cream bars. Shops with names like Niagara, Golden Gate, and New York prepared the ingenious menus.

Interior of a Greek milk bar in Adelaide

Greeks in Australia, many of whom had visited the U.S., had relatives there, or had worked in American food businesses, were fascinated with the drug store soda fountain and its creamy and syrupy refreshments. Mick Adams (born Joachin Tavlarides) pioneered the milk bar trend. The budding entrepreneur, who had traveled in the U.S., was taken with the stand-up soda fountains he had seen there. What a perfect complement to the table trade, he figured. He was thrilled by its potential for quick turnaround service.

In November 1932, Adams launched the Black and White Milk Bar, the first in what would be a chain of cafés. A savvy promoter, he invited Lord Mayors to his opening. Five thousand customers, Alexakis and Janiszewski estimated, thronged his establishment on its first day. The crowd was so big that the police were forced to close the road to traffic.

Adams shrewdly marketed his product as a “health food.” Originally prepared with milk, the shake only later added ice cream. Other novelties were also on offer at milk bars. Spiders (ice cream sodas) and fizzy drinks infused with pineapple, lime juice, sarsaparilla, and bananas, were favorites. The businesses enhanced their appeal by making their own syrups and using fresh fruit in the confections.

Hamilton Beach milk shake mixer

American know-how revolutionized the milk bar. Adams, a fan of American soda fountain technology, led the way in introducing compressors, pumps, and other machines. The electric Hamilton Beach milk shake maker was an early American import.

The milk bar craze exploded. By the end of 1937, Alexakis and Janiszewski point out, 4,000 milk bars had opened. Alluring sundaes with an American style highlighted the menus. The American Beauty featured a tall glass layered with fruit salad, ice cream, and wafers. Ice cream at the cafés imitated the American sweet’s hallmark smooth and creamy textures and sweet taste.

The allure of American refreshments attracted customers. “Soda water bubbled and hissed into tall glasses with flavoring and ice,” Maria Cominos, who ran a café with her husband, remarks. “Sometimes it was topped with ice cream…. [soda fountains] attracted people from miles around because they were new, they were American, they (soda drinks) were affordable, and only we had them.”

British boiled sweets and lollies were replaced with milk chocolate and hard sugar candies. The shops made many of their own items. (In Chicago, the capital of the Greek immigrant candy business, ice cream was frequently a staple of the candy stores. The Dove bar was conceived in a small Greek-owned candy shop in that city.) The Greek café in Australia stood out, with its window displays of chocolate bars, sugar candies, other sweets, and inviting fruit.

Art Deco counter at Australian milk bar

The café decor had a Hollywood sheen. Art deco designs, often with a California motif, lent glitz and glamour to the interiors. The owner of the Niagara Café, Jack Castrission, described its lavish display: “ … all coloured glass and shiny metal surfaces, large reflective mirrors, polished marble,… a domed ceiling design filled with stars and the night sky…. It was a pleasure palace, and the locals loved it.” The cafés conveyed a mythic image of a faraway land. “Selling a dream,” Alekakis and Janiszewski contend, the cafés were “to a degree, a ‘Trojan horse’ for Americanization.”

The milk bars were hangouts for Australian youth. By the early 1950s, jukeboxes began appearing. They pulsed with tunes from Bill Haley and the Comets and other early American rock bands. Dress and hairstyles often mimicked American fads. Teenagers could dance, gorge on ice cream sundaes, and soon bite down on another American import—the hamburger.

The cinema and the milk bar business were intertwined. Often located near the town cinema or selling refreshments from a counter inside, the cafés depended on the movie trade: “It was a meeting place for young people … a real money spinner,” Julie Canaris described her parents’ milk bar that sat next to a movie theater in the city of Darwin. “It had ice creams…. We also sold milk shakes, lemon and orange squash, scorched almonds, cherry ripes, boxed chocolates, cigarettes, and tobacco…. Our main aim was to serve as many customers as possible during the interval.”

Australia’s Greek cafés have in recent years lost favor as their clients’ tastes changed. The sit-down meal trade lost out to the take-out culture. Both owners and patrons were aging. Television viewing was also weakening the pull of both cafes and their movie theatre partners.

Milk bar in Melbourne

Besha Rodell, a New York Times writer, remembers the milk bars as a “third place,” “one part corner store, one part candy shop, and sometimes a deli or news agent or neighborhood social club.” Revisiting Melbourne, where she grew up, she was saddened by the disappearance of the business where she experienced her “first taste of consumer lust.” Convenience stores and supermarkets, once prohibited from selling on Sundays and even Saturdays, were supplanting the venues of her youth. She spotted the “ghosts of milk bars, which have been replaced by colorless shops, residences, and wine bars.”

There were other forces undermining the café. The children of the shops’ founders were often reluctant to follow in their parents’ footsteps. “There wasn’t the natural passing on of the café to the kids,” café historian Risson explains. “They became doctors, lawyers, pharmacists, and accountants.” Moreover, the shops, she says, were a stepping stone for the pioneers. “They were never meant to be forever. They were a way of forging a new life.” Similarly, many of the children of Greek diner owners in the U.S. have forsaken its backbreaking toil for white collar professions.

Cafés and milk bars may be fading, but their legacy is enduring. Many Australians still remember fondly the cries of “I’ll meet you at the Greeks.”

Greek Cafes & Milk Bars: book cover

Note: Greek Cafés & Milk Bars of Australia, a book by Effy Alexakis and Leonard Janiszewski, was a discovery for me. For a writer who had chronicled America’s Greek food business, it was a revelation. The volume, a gold mine of material, was invaluable. Unless otherwise identified, quotations are from this book.