“Why Are All the Pete’s Restaurants Named Pete’s?”

“Why are all the Pete’s restaurants named Pete’s?” the headline of a story in the January 9, 2000 Greenville News asked. The reporter, Mike Foley, observed that these eateries in the South Carolina textile town and the surrounding upcountry area were more likely to be run by owners with Greek names like Spiros and Georges. But “that doesn’t stop customers asking for Pete when they walk in the door, sit at a Formica-top table and get a whiff of hamburgers grilling and onion rings frying,” Foley writes. “Everybody says, ‘Where’s Pete? Where’s Pete?’ said George Mastorakis, owner of Pete’s Drive No. 7 in Greek,” the article continues. “But there’s no Pete.”

The common names can cause confusion among customers, Foley notes. People forget where they had dinner or ordered takeout. “I’ll have people call here and complain,” one operator told him. “I’ll have people call here and complain. They’ll say they just came in here and got an order of jumbo shrimp here. They just pick the wrong number out of the book.”

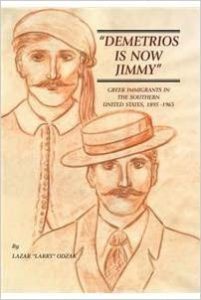

Eager to fit in, Greek businessmen were afraid to call attention to themselves. Foreign names, even serving ethnic food, were roadblocks to Americanization. In Southern towns, the newcomers were easy targets for the xenophobic. In the early 20th Century, the Atlanta Constitution, scholar Marni Davis reports, frequently tarred Greek merchants as “dagoes.” A name change was a characteristic response. “Demetrios Is Now Jimmy,” historian Lazar “Larry” Odzalc titles his book on Greeks in the South.

Fleeing the rugged, unforgiving land of the Peloponnese peninsula at the turn of the twentieth century, Greeks journeyed to South Carolina. Although we associate Greek immigrants with big cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago, the South was also a popular destination. Mostly bachelors, the pioneers sought out Southern cities whose economies were expanding. The “New South” was advancing, growing into a commercial and industrial region bursting with employees needed to run the factories, insurance companies, and sales offices. Entrepreneurially minded Greeks spotted an opening for their talents. The workers were consumers and the immigrants saw themselves as providers for their wants. They built food businesses to cater to the working and middle classes. The innovators were breaking new ground in the South, creating a niche where none existed.

The early ventures in South Carolina suited the Greek temperament. Averse to toiling as hired hands in mills and factories, the newcomers yearned to be their own bosses. Selling produce from pushcarts was a common starting point. Candy shops, a favorite business of Greek immigrants throughout America, were another stepping stone. These businesses often sold ice cream, sandwiches, and other quick fare. Three such stores, historian Judy Bainbridge points out, had opened by 1907 in downtown Greenville. From sweet shops, Greeks often embarked on the restaurant or, more specifically, the quick lunch business. By the middle of the 1920s, Bainbridge says, the budding ethnic merchant class dominated Greenville’s food business. By that time, 14 Greek lunchrooms were serving hot dogs, sandwiches, and similar items that did not offend Southern tastes.

Storefronts with comforting names like Tom’s Nickel-Up, Post Office Café, and Quick Lunch betrayed little of their owners’ origins. Their locations were shrewdly chosen. In Greenville and other South Carolina towns, the Greeks set up shop on the main commercial downtown streets.

News of the alluring opportunities in South Carolina spread. Eager to replicate their success, kinfolk of the owners headed for South Carolina. “An immigration chain led family members and others from the same village to settle here,” historian Bainbridge writes. The new arrivals capitalized on these connections. Finding a job in a kinsman’s restaurant and learning the ropes was excellent preparation for opening one’s own business. Journalist Foley describes a Greenville eatery, owned by Spero Contis, where new immigrants apprenticed. “Pete’s Original served as a makeshift training school for restaurant owners. Most all the Greeks who work in the business have worked here,” Contis said. A constant stream of immigrants thus replenished the Greek food trade.

The entrepreneurs gradually put down roots. The early colony of bachelors blossomed into a settlement of families. More and more Greeks left the city for homes in the suburbs. Craving acceptance, Bainbridge notes, owners joined the Masons, Odd Fellows, and other societies. The immigrants were assimilating but still clung tenaciously to their traditions. During the Thirties, families joined together to build the St. George’s Greek Orthodox Church. During World War II, congregants demonstrated a patriotic spirit. They bought war bonds and raised money to purchase a plane. The women of the church, Bainbridge recounts, put on a “spaghetti dinner Greek style” to raise money. St. George’s would organize regular festivals featuring Greek food, music, and dancing, which won friends among the locals. Nick Theodore, an insurance executive active in the church, personified the Greek ascent into the mainstream. “Uncle Nick,” whose parents emigrated from Sparta, was the first American of Greek ancestry elected to the South Carolina state legislature. Theodore went on to serve as the state’s lieutenant governor from 1987 to 1995.

The new generation of Greek restaurant owners is bolder than the lunchroom pioneers. More Greek food is on offer in the Greenville area, even if it is sometimes altered for the Southern palate. Tzatziki, souvlaki, spanakopita, pasticcio, and other Greek standards attract a curious and adventurous clientele. No longer reticent, the merchants broadcast their ethnicity with restaurant names like Ji-Roz, Kaires Mediterranean, and Greektown Grill. Old school owners would have been proud of their successors.