“Is it not the case that young persons of both sexes hang about and loaf in the ice cream shops?” In a hearing before a Joint Parliamentary Committee on Sunday Trading in 1905, the Duke of Northumberland inquired about Glasgow’s growing number of Italian-owned businesses. By that year, more than 336 parlors were operating in Scotland’s largest city. A committee member worried that children were wasting their pennies on ice cream instead of putting them in “missionary boxes” in Sabbath school. Sunday selling of confections was causing consternation among upright Glaswegians. In a paper on “Ice Cream and Immorality,” presented in 1991 to the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, Francis McKee detailed abundant evidence of the chilly reception the city’s elders gave this immigrant trade. Why did this refreshment, which was gaining popularity in the booming industrial city, arouse such horror? McKee offers some intriguing answers.

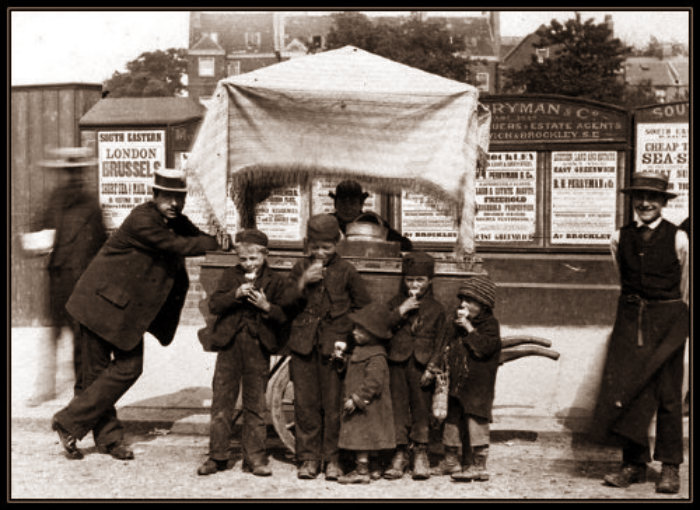

From the 1880s to 1920, Italian immigrants were leaving struggling peasant conditions behind to better their lot in Scotland’s expanding economy. The newcomers, like those in other parts of Great Britain, came from particular regions of Italy. The settlers in Scotland frequently hailed from the area around the town of Bardi in Tuscany. (Italians there today often speak with a Glasgow accent.) Some started as street musicians, while others vended plaster statuettes. The next step up on the opportunity ladder was hawking ice cream, a popular vocation for Italians throughout Great Britain. “Hokey Pokey” men wheeled their barrows through the streets. From these ventures, many moved up to more remunerative employment. Vendors opened small shops that sold ice cream in the summer and hot peas and vinegar in the winter. Over time, the Italians also began selling fish and chips.

Larger and more prosperous businesses were built. “They graduated from rudimentary shops in the slum quarters to more luxurious establishments … with lots of mirrors on the walls, wooden partitions and leather covered seats,” historian Bruno Sereni recounts. Stringing together several parlors and installing kinfolk, friends, and former employees in them, successful merchants enlarged their industry. Youngsters who the owners recruited from their home towns in Italy and who displayed a talent for business were rewarded with a shop to run. The new partner received all the necessary equipment, furnishings, and supplies—milk, sugar, cigarettes, and chocolates—from his benefactor.

The ice cream business in the Glasgow area mushroomed. From 89 shops in 1903, their number jumped to 336 in 1905. The Italian community also burgeoned, reaching 4,500-5,000. Immigrants who had once dreamed of returning home and buying land, put down roots.

The immigrants infused Glasgow, a mighty industrial city, with their commercial fervor. During the early twentieth century, the metropolis led the world in heavy engineering and shipbuilding. The arrival of ice cream shops, along with cinemas, dance halls, cafés, and other entertainment for the working and middle classes coincided with this burst of prosperity. For some straight laced Glaswegians, these indulgences were threatening. Upright citizens in this heavily Presbyterian city feared an incursion by Italian purveyors of pleasure. In the eyes of the city’s “conservative forces,” McKee points out, ice cream shops “epitomized the evil of luxury being smuggled into the souls of Glaswegians.” The product was frightening, she says, because it represented “something so obviously luxurious, unnecessary, and ephemeral.”

Hatter’s Castle, a novel by Scottish writer A.J. Cronin published in 1931 that McKee quotes, describes a young woman’s initiation into the forbidding world of ice cream. Denis takes his girlfriend Mary to an Italian café in Dumbarton, a community near Glasgow. “Before she realised it and could think even to resist, he had drawn her in inside the cream-coloured doors of Bertorelli’s café. She paled with apprehension, feeling that she had finally reached the limits of respectability, that the depth of her dissipation had been reached.”

Ice cream, authorities feared, was a menace because it led the young on the path to perdition. A police inspector at a hearing in 1906 warned that the shops were promoting women’s “downfall.” Twelve- and thirteen-year-olds had been lured into prostitution by boys who were “going out acting as their bullies at night.” “Boys have been known to begin a course of vice owing to connections formed in these shops,” one officer alleged. To the apostles of propriety, the Sunday hours of the parlors were also reprehensible. A letter to the editor of the Glasgow Herald a blogger uncovered, portrayed the shops as “perfect iniquities of hell itself and far worse than the evils of the Public House.” To stymie them, reformers pushed through daily 10 p.m. closing laws and total Sunday closure.

Their accusers impugned the character of the Italians. “A good sober minded Scotchman at the head of the shop would not allow any nonsense. The ice cream parlors are not conducted in a satisfactory manner—they are mostly run by Italians,” one Glasgow officer alleged. In a city known as the “workshop of the world,” aliens, Catholics no less, were instilling injurious values in their young customers. Teenagers in the shops, one witness warned at a Sunday closing hearing, were “kissing and smoking and cuddling away at each other.”

The ice cream merchants fought back against the hostility and gradually won acceptance. The clash between the immigrants and the respectable classes resembled “una battaglia,” a battle, the colorful image historian Nicoletta Tranchi uses. The parlors established themselves, some upscaling with lots of mirrors on the wall, leather seats, and other decorative features. Bold dealers built chains. For the Scots, “Going to the Italian” turned into a pleasurable pastime.

Many cafés expanded their offerings to include fish and chips, mushy peas, and other quick items. The shops also concocted new ice creams—spiced oreo, passion fruit cheesecake, toffee crisp, and other “artisanal” fare.

The Scots may have acclimated to the once frightening ice cream parlor. But the experience can sometimes bring a shudder to the customer. The Aldwych Café and Ice Cream Parlor in Glasgow sells Respiro del Diavolo (“Breath of the Devil”), an incendiary confection made from the Carolina Reaper pepper. Buyers must sign a waiver before trying a flavor that caused one buyer, according to Canada’s National Post, “to feel thunderclap headaches.” The waiver absolves the business from responsibility for any personal injury, illness and possible loss of life.

To read more about the Italian ice cream merchant in Great Britain, see my piece, “I Scream, You Scream: Italian Peddlers and Coal Miners.”