Mini hot dogs draped in “zippy sauce” entice customers to the Famous Lunch in downtown Troy, a once mighty upstate New York industrial town on the west bank of the Hudson River. The small eatery was founded as the Quick Lunch in 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression. Their signature hot dog comes with all the “works”: onions, mustard, and a pungent dressing. It’s is a “chewy meat sauce,” Scott Vasil, the latest member of this Greek clan to run the place, told me. One can only guess the secret behind the condiment’s flavor. Some may think it redolent of the old world, of Greece and the Ottoman Empire.

In addition to its Greek immigrant lineage, the shop has other ethnic connections. The three-inch franks were originally made for the business by the Troy Pork Store, a German butcher shop near the lunch counter. The hot dogs are nestled in miniature rolls custom-baked by Bella Napoli, a local Italian enterprise. The Famous sits in what food writer Robert Sietsema dubbed “Tiny Frankfurt Territory.” The area, in New York state’s Capital District near Albany, is home to several eateries showcasing this regional favorite. Traveling around the region, a shop window caught Sietsema’s eye. He was captivated by the sight of a “griddle with tiny hot dogs lined up like soldiers.” He had spotted the Famous Lunch Room.

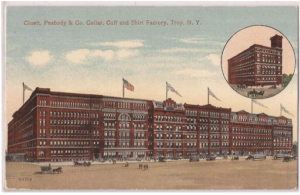

Once the country’s fourth largest city, Troy was fertile ground for the mini hot dog business. A prosperous manufacturing community in the 19th century, it competed with Pittsburgh and Buffalo in the production of iron and steel. The “collar city,” where the technique of making detachable collars and sleeves originated in 1840, was America’s leading maker of these products. Cluett, Peabody and Co., which would become Troy’s largest industrial company, manufactured the Arrow shirt there. By 1901, the city boasted 26 mills turning out collars, cuffs, and shirts.

Hugging the banks of the Hudson River, factories thrived because of the large supply of sand, charcoal, iron ore, limestone and other raw materials. Troy’s plentiful resources facilitated the manufacturing of a host of metal goods. Nails, spokes, horseshoes, railroad iron, stoves, and bells were assembled in the early factories. During the Civil War, Troy concerns furnished horseshoes for the Union cavalry, plates for the ironclad ship, the Monitor, and clothing for the Union army. The Rensselaer Iron Works was the first American plant to use the efficient Bessemer process to make steel. Metal goods were not the only products manufactured in the factory city. At their height, Famous owner Scott Vasil notes, 19 breweries operated in Troy.

At the juncture of the Hudson and Mohawk Rivers, Troy had a strong advantage. Water powered early industries. The construction of the Erie Canal, with Troy at its terminus, provided the city with a cheaper and faster passageway for raw materials and manufactured goods. The town’s location was a major source of its allure for new businesses and job seekers. “Its rivers go all the way to Canada and New York City,” Scott said.

Burgeoning industry attracted an immigrant working class. The Dutch, English, and Scots led the way. A large Irish influx in the early 19th century supplied willing hands for both the collar and cuff factories. Irish women predominated in the apparel business. Kate Molloney, an Irish woman, organized the country’s first female union, the Collarworkers Union, in 1864. Helen of Troy, a 1923 Broadway musical written by George S. Kaufman and Marc Connelly, celebrated the women of the city’s collar shops.

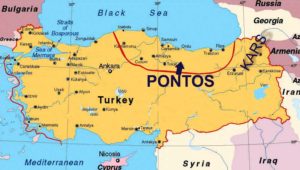

In the early 20th century, an influx of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe (Poles, Italians, Jews, Greeks) created a polyglot community. Fleeing harsh economic conditions and driven to improve their lot, the Greeks settled in Troy. A sizeable group of arrivals were refugees escaping brutal oppression by the Ottoman Turks in Asia Minor, the peninsula between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. Starting in 1914 and culminating in 1922, the Turkish occupiers waged a campaign of persecution and violence against the large colony of Greeks in the region. Their objective, Scott Vasil’s uncle Edward Nicholas points out, was a simple one—to “kill Christians.” Those not slain were to be expelled. Nicholas grew up in Pontos, a Greek name for the area on the southern coast of the Black Sea. Edward, who still gathers with his compatriots in an ethnic society, found refuge in Troy. (Greeks from different regions clustered in different parts of New York State. Those from Peloponnesus, Edward said, were likely to put down roots in Schenectady.)

“Distrustful of government,” Edward’s daughter Despina Nicholas says, the outsiders turned inward, relying on each other to build a new home. In the early days, the Greeks huddled in boarding houses in this city of brick tenements. A kaffenion, the traditional coffee house, offered companionship and entertainment for the uprooted. Over time, immigrants married, formed families, and constructed a tight-knit community. At its height, Despina estimates, there were 200 Greek families in Troy. (In recent decades, many have moved to outlying areas.)

The Greeks needed an anchor for their settlement. The Pontic emigres provided the “momentum,” Christina says, for founding a church. St. Basil Greek Orthodox Church was established in 1931. The church united the immigrants into a cohesive group, a kinotis. It still “glues the families together,” Scott Vasil says.

The immigrants had a difficult time assimilating. The Greeks, for example, were a “little more exotic” than the Italians, Despina observes. Since they also possessed their own distinct liturgy, the Greeks required their own place of worship. The Italians joined mainstream Catholic churches and hence became “more integrated into American society,” she notes.

Armed with their faith, the Greeks pushed ahead in search of a livelihood. For some, the flourishing factories of the “collar city” beckoned. An aunt of Scott’s found a job at Cluett, Peabody, the shirt collar firm. Troy’s real lure for Greeks, whatever jobs they had to take, was the opportunity the bustling urban economy provided for self-employment.

The new immigrants were particularly adept at creating small businesses. Perhaps the earliest to arrive, Despina Nicholas found from her research, was Tom Valis. Valis, who settled in Troy in 1905, found a room at an Irish boarding house. In 1911, he was joined by his brother and wife. Although many of the details of his career need to be filled in, Valis, Despina discovered, ran a shoeshine shop, an entryway for entrepreneurially minded Greeks all over the country. (A 1909 survey done of New York City bootblack parlors, cited by scholar Charles Moskos, found 151 Greek-owned shops in Manhattan.)

Newcomers established themselves in a wide range of fields. The sponsors of the celebration of Greek Independence at the St. Basil Church on April 19, 1942 included Greeks from the lunchroom, cafeteria, paint store, family restaurant, flower shop, milk delivery, candy store, and gas station businesses.

After stints operating a grocery store and a butcher shop, one enterprising Greek immigrant opened the Quick Lunch in Troy in 1932. Fearful of looming dangers, Chris Seamon, the great uncle of Scott Vasil, the present proprietor, left Pontos in the early 1900s and thus escaped the later massacres. Chris helped newcomers get on their feet, frequently offering them a place to bed down in his house.

The lunchroom, which was passed on through the extended Greek family to Chris’s nephews Steve and Nick Vasil in 1955, “still is very much working class,” Don Rittner, a historian of troy, told me. At its peak, Scott Vasil points out, the shop fed off the city’s commercial energy. “Congress Street was very busy,” Scott commented to writer Amy Halloran. “There was enough business for everybody to go around. Everybody was thriving. The city was real lively . . . you had work—factories, companies, everything was running three shifts, the steel mills, the breweries. You could support local businesseswe were open 24 hours a day.” (Scott took over the shop in 1995.)

Even now, the Famous seems “frozen in time,” author Amy Halloran observes. Its counter stools, formica tables, and booths are a throwback to a simpler, more down-to-earth era. The “walls are still lined in shiny enameled steel,” Halloran observed in an admiring piece. An “eye opener” for Amy, who started going to the Famous in the early ’80s, the lunchroom was the “lair” of construction workers and other ordinary folks. They were bound together by the homey atmosphere and its “super cheap, super fast food.”

The Famous “defied the logic of target demographics,” Scott’s cousin Despina says. It “appealed to every generation, every socio-economic group.” The owners created a setting congenial to “lively political and intellectual debate,” she adds. One of the shop’s regulars, Fire Department Captain Robert Paul echoed her remarks: “I’ve been coming here for 35 years and me and Steve solve the world’s problems, do the Jumble in the newspaper, then talk about the headlines of the day,” he told Bob Gardiner of the Albany Times Union.

The Famous’s stock in trade is filling, American comfort food, and the owners have not tinkered with the fare. The only echo of Greece is the shop’s rice pudding. “Whatever I got at 19 was still on the menu,” Halloran remarks. Besides hot dogs, customers line up for breakfast items like omelettes, pancakes, and French toast.

Writer Rittner cherishes memories of eating there. “As a boy living across the street, I would run over to the Famous and wolf down 8 dogs, French fries, and a Canada Dry,” he writes. Just lingering in the shop heightened his enthusiasm: “I loved sitting in the booths. The wooden backs seemed to go up to the enameled steel ceiling. Each booth had a small ‘Juke Box’ connected to the main player that was sitting by the phone booth at the far end of the eatery. A quarter got you three plays, mostly Elvis. I would sit there for long periods of time, between bites, listening to the debates about everything under the sun.”

The Quick Lunch became the Famous Lunch because of a marine stationed in Moscow who craved hot dogs from his hometown eatery. In 1958, Corporal Gordon Gundrum, based at the U.S. Embassy, planned “Operation Hot Dogs,” a mission to bring his favorite mini franks to Russia. The embassy arranged with Royal Dutch Airlines to fly in a few dozen hot dogs for the Ambassador’s 54th birthday. The story was picked up in the media, leading to cachet for the shop and its new name. The business was shocked one day when the Jay Leno show called ordering 250 mini dogs. (After initially thinking the phone call was a hoax, the Famous ended up filling the order.)

Why did mini dogs sprout in Troy? The story is murky. Asked about it by Chuck D’Imperio, the author of A Taste of Upstate New York, Scott Vasil replied: “I really don’t know,” he laughed. “I mean, they sure didn’t eat them in Greece. But for some reason many generations ago, several different Greek families showed up in this area and started the tradition.” All the shops had their own mixture of sauce, Scott’s uncle Edward Nicholas said: They vied with each other, but it was friendly competition, a “my sauce is better than yours” attitude, he added.

D’Imperio is an upstate New York writer, whose book includes a lively guide to these hot dog outposts. His interest in the Greek hot dog business was sparked by Johnny’s Hot Dogs, an Albany joint he “used to haunt” during his college days. The owner was a “big garrulous man with thick Coke-bottle glasses and a hard-to-pronounce Greek last name,” D’Imperio recalls. He was a “friendly-giant sort of guy, despite the small handgun peeking out of his waistband or hidden under the counter.” The shop sold mini dogs accented with a mysterious Greek sauce that filled a large vat. A former employee recounted the attractions of the “colorful place.” “Many of the older customers remembered Legs Diamond, the famous gangster who was shot around the corner at 67 Dove Street back in the 1930s. A couple of bookies frequented the restaurant, too, but as far as I could tell, never ate there.”

The first stop on D’Imperio’s tour of mini hot dogs in the Collar City area is “Hot Dog Charlie’s.” Opened in 1922, the business paved the way for similar businesses. Founded by Strates Fentekes, a Greek immigrant, the shop was first called the New Way Lunch. Strates had earlier worked as a bootblack, the U.S. Census reports. He took the name Charlie, D’Imperio points out, because customers had difficulty pronouncing his name. A showman, Fentekes was famous for the “hairy arm serve,” D’Imperio relates. “He would line the mini dogs up in a row on his hairy Greek forearm and then slather them with all the fixings, one after another.” His technique, which other Greek merchants would duplicate, was ultimately banned by the Health Department. Charlie’s spawned more shops run by younger members of his family. Unlike the Famous, the chain adopted a more modern, streamlined look well suited for shopping center venues.

Gus’s Hot Dogs, another purveyor of the mini frank, is more akin to a roadside stand than its fellow businesses. It was established in Watervliet, a town across the river from Troy, by another Greek entrepreneur, Gus Haita. The shop sells the “original” frank, garnished with its trademark meat sauce, from its window. Its menu now includes Greek burgers topped with that special sauce.

Writer Sietsema provides a colorful depiction of Gus’s, which he visited in 2013: “I’ll never forget the first time I went there in the dead of winter—the fry cooks were wearing bubble parkas and huddling together near the stove. The stove itself was just a giant rectangular griddle with a ridge around it, which filled up with grease as the day progressed, proving the perfect medium to cook hot dogs and hamburgers.”

The story of Troy’s lunchrooms is bound up with the larger saga of Greek immigrant life in America. Between 1900 and 1920, there was a surge of newcomers. During that time, 400,000 Greeks arrived in the U.S. Although waves of Greeks streamed into factory towns to labor in steel mills, shoe factories, textile mills, and on railroad gangs, for many, these jobs were simply way stations. Greeks grew restless with the workplace regimen and bridled at working for a boss. Self-employment was the answer. Peddling fruits, working for a kinsman in a shoeshine business, or selling flowers were common launching pads for budding entrepreneurs. The aspiring merchants also spotted an opening in the food business. The burgeoning workforce that thronged the cities hungered for quick, cheap food.

Greeks latched on to the hot dog trade to capture these potential customers. The hot dog, the product’s foremost historian, Bruce Kraig, argues, was a “uniquely American food,” on which successive groups of immigrants have put their stamp. German butchers and vendors marketed sausages in city neighborhoods as early as the mid-19th century. Other innovative ethnics like the Polish Jewish immigrant, Nathan Handwerker, also contributed. In 1916, he opened Nathan’s Famous in New York City’s Coney Island, a restaurant that popularized all beef hot dogs with a garlicky zing.

Savvy Greek vendors took to the streets to hawk their product. In early 20th century Chicago, the largest center of Greek immigrants, they sold “red hots” from carts and lunch wagons outside factory gates. The “pennies business,” might produce a healthy nest egg for future ventures or for investing back home. The Greeks had discovered a toehold from which to climb the economic ladder. The hot dog business, historian Bruce Kraig remarks in a posting from cbsnews.com, was a godsend for new Americans: “I mean, the immigrant experience, people came with no money at all. And you could buy, let’s say we’re talking about 1900, you could buy a sausage for a penny and the other accouterments for a penny and you sell it for a nickel. And that’s the way you move up in the world, and this was an American idea.”

From the hot dog stand, graduating to a lunchroom or even a restaurant was a sensible decision. A 1919 article in the Greek Star, a Chicago newspaper cited by scholar Charles Moskos, describes this route: “At that time the dinner pail was the emblem of the American workingman, and it seemed likely to continue to be so, because no one had thought of the idea of creating a restaurant to serve this man. Then the Greek came. He drove his lunch wagon at the noon hour to the factory district, and was popular from the start. Later he opened restaurants close to the factories, serving food at prices which appealed to the laborers, and eventually he won a reputation for himself.”

Soon, Greek-owned lunchrooms serving up hot dogs, pie, coffee, and other basic fare began springing up in industrial towns across the country. “Lunchrooms,” as they were commonly called, was an apt name. These no-frills places were forerunners of the Greek diners of the 1950s and 1960s that also catered to a blue collar crowd.

Fall River, a Massachusetts textile town, was an early lunchroom stronghold. Nick Pappas started Nick’s Coney Island Hot Wieners in 1920 to sell hot dogs with a spicy sauce. The Spindle City was tailor-made for shops commonly located outside factories. “In Fall River, the popularity of hot dogs began with the mills,” one Coney Island merchant told Parris Kellerman of the Standard Times. “People couldn’t afford a lot or to sit down for meals.”

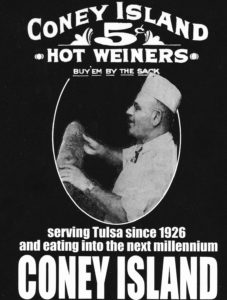

The Coney Island Lunch, which opened in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, a steel town outside Pittsburgh, in 1919, was another such business. Christ Economou, an adventurous Greek, founded the shop, the first in a string of similar eateries he built. The family patriarch “followed the railroad tracks down the East Coast and opened 26 Coney Island shops—selling them to Greek immigrants so that they could also bring their families to America,” granddaughter-in-law Vicki Economou recounts in the business website. After a sojourn in Texas, Economou landed in Tulsa, Oklahoma and founded the Coney Island Hot Weiners in 1926. (The name was spelled this way because the owners used the unique spelling of wieners to retain their copyright.) His son, Jim, points to the basic principle for his father’s success with the 5¢ hot dog: “My father said that hot dogs were an easy food people could take in their hands and eat on the go,” he remarks to the Tulsa World.

The lunchrooms had a common drawing card, their hot dog sauce. Although the mixture may have been different in details, the fragrant topping was typically made with a blend of Greek spices. The seasoning was reminiscent of the flavoring used for the dishes pastitsio and moussaka. “They wanted to put an added value on their hot dog,” historian Kraig pointed out to Cody McDevittt of the Pittsburgh Gazette. “There weren’t a lot of toppings on hot dogs in those days. So the sauce, when you look at it, it is tomato based with spices like nutmeg and cinnamon.”

The sauce, which so many have tried to decipher, gave the product a mystique. Sam Contacos, whose grandfather founded the Coney Island Lunch in 1916 in Johnstown, another Pennsylvania industrial town, described the allure of its flavoring in an interview with the Daily American:

Sam Contacos laughs when he hears people claim to have the recipe for Coney Island’s famous chili. Truth is that no one knows it but him. His grandfather showed it to his father, who in turn taught it to Sam. The recipe is in a safe deposit box. Those three men are the only ones who ever knew what went into it.

“We’ve made it the same way for 100 years. . . . They let it cook for hours. Chili used to cook all day before it was finished. It’s not a product that you can make in a half-hour or two hours or three hours. You start it at 8 o’clock in the morning and finish it up at 7 o’clock the next morning. Then you clean the pots and start all over. All these fantastic recipes they have on the internet . . . sorry, not even close.”

Other tantalizing riddles surround the Greek hot dog trade. Why the name, coney, for example? A common explanation is that many future Greek merchants arriving in the U.S. went through Ellis Island and, during their stay in New York City, savored the hot dogs they ate on Coney Island. Perhaps for newcomers fearful of being branded as “foreigners,” the name carried a reassuring American feel. The guessing game will undoubtedly continue.

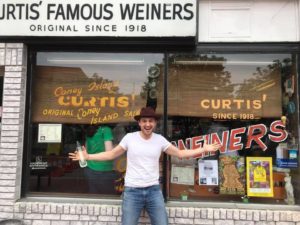

Whatever its origin, the name stuck. It was so infectious that Greeks who fanned out to the heartland often called their shops “Coney Islands.” George Margeas, who in 1918 launched Sioux Falls, Iowa’s first hot dog shop, named it the Coney Island Wiener House. He was thrilled to be selling America’s first “fast food,” according to one newspaper account.

Detroit, the mecca of the industry, is steeped in Coney Island folklore. Greeks (and also Macedonians) founded the hot dog trade in the motor city. In 1916, immigrant Constantine “Gust” Keros, who had been a shepherd in a small Greek town, landed a job sweeping floors at Detroit’s Kelsey Auto Plant. To make ends meet, he moved on, setting up a tiny street corner business. He sold popcorn, shined shoes, and cleaned hats, and, ultimately, hawked hot dogs from the same location. Keros opened a lunchroom, American Coney Island, in 1917. Seven years later, Gust and his brother William began operating another eatery, Lafayette Coney Island, side by side with the American. Their mainstay was the coney, a nickel hot dog slathered with a meaty sauce, fragrant with cinnamon and allspice. The factory town was ripe for the lunchroom business. “Coney Island lunch counters were supercharged in downtown Detroit in the 1920s,” Katherine Yung and Joe Grimm, authors of Coney Detroit, point out. “At that time, there were so many workers packed into the city that some had to rent rooms for just 8 hours a day—other workers rented the other hours. They had to grab lunch in a crowded hurry. Coney Islands, with your food and change in front of you in just a minute or so, were the answer.”

Coney Islands mushroomed in Detroit, as relatives and workers in the early shops left to open their own eateries. Neon signs announced these enterprises, which spread throughout the city. Aspiring merchants expanded the trade to Flint, Jackson, and other nearby communities. Their struggles paid off. “Coney Islands became their ticket to the American dream after years of hard work,” Yung and Grimm observe. Today, more recent immigrants—Albanians and Yemenis—have broken into the business.

The history of coney islands is replete with tall tales or perhaps just embellishments of early stories. Two Greek immigrants who learned the candy trade from a countryman in Johnstown, Pennsylvania moved to Cumberland, Maryland in 1905, the story goes, to open a candy and ice cream business. A Greek peddler from Texas, carrying a “little burner on his back,” sold them on a tempting idea. “He had a special sauce they could make money with,” Louis Giatras, the owner of the business, told me. After the partners sampled the sauce, they were persuaded and started making coney island hot dogs with it. The Coney Island Lunch, a combination short order food and candy, ice cream parlor, blossomed into the Coney Island Famous Wiener Company.

Ingenious Greek merchants continued to craft new variations on the coney. The hot Texas wiener, it is said, was dreamed up in the silk mill town of Paterson, New Jersey, in the 1920s. Its originator, an anonymous elderly Greek who operated a lunch counter in the city’s downtown, wanted to spice up his hot dog. Dabbling with different mixes, as folklorist Timothy Lloyd tells it, he seized on one, which resembled a “Greek spaghetti sauce.” The blend played chili and cumin off against cinnamon and allspice. Grills, as Paterson’s lunchrooms were called, imitated his formula. Their wieners were fried, put on a steamed bun, and then topped with successive layers of mustard, onions, chopped onions, and the fiery sauce. The shops, many located along the Passaic River near the mills, gradually added hamburgers, roast beef sandwiches, and BLTs to their fare. After that, “Texas wieners” headlined the menus of other Greek-owned restaurants across the country.

In Providence, Rhode Island, another marketing gimmick took hold. Countermen perform an “acrobatic show” known as “upd’ahm,” the Greek Chef blog writes. In the New York System, “they hold one arm out, line as many as a dozen buns from finger tips to shoulder, squeeze in the wiener (don’t call it a hot dog!), hit with the yellow mustard, spoon on the meat sauce (don’t call it chili!), place on chopped onions, and dust with celery salt.”

A young Greek immigrant in New York City, Constantine “Gus” Poulos, started a craze by pairing hot dogs and papaya juice. Poulos, who was introduced to papaya and other tropical juices on a vacation to Miami, hatched a plan. He began offering a papaya drink at his shop on 86th Street and 3rd Avenue in Manhattan. The early juice bar evolved into a business called Papaya King. Since his shop was in Yorkville, a large German enclave, Poulos added hot dogs to his menu. Other merchants followed suit and soon there were a plethora of imitators with names like Original Papaya and Prince of Papaya.

In Rochester, New York, Greek immigrant Alex Tahou conjured up another hot dog dish whose fame would spread. In 1918, he opened a lunchroom in what was once the train station for the Buffalo, Rochester, and Pittsburgh Company. He called the shop West Main Texas Hots. During the Depression, Tahou started selling a workingman’s plate of “red” hots (standard franks) or “white” hots (a pale sausage like the German weisswurst sausage) topped with chili sauce over a bed of home fries. Spurred on by college students infatuated with the dish, new generations of the Greek family converted the “hots and po-tots” into the “garbage plate.” Customers could order a choice of meats and a myriad of sides, like baked beans and macaroni salad, with the dish. Inevitably, other area restaurants jazzed up their offerings with “dumpster plates,” “sloppy plates,” “trash plates,” and similar renditions.

The hot dog trade is just one example of the Greek affinity for the restaurant industry. Greek immigrants old and new have gravitated to a host of different food businesses, from lunchrooms, diners, and pizza shops to family dining venues, steakhouses, and seafood places. This proclivity was evident very early in the American Greek community. By 1913, sociologist Charles Moskos estimates, Greeks owned 600 eating establishments in Chicago, an immigrant hub. Their dominance scared suspicious Chicagoans, restaurant historian Jan Whitaker points out. They feared that the newcomers were “invading” the lunchroom trade. The adage, “When Greek meets Greek, they start a restaurant,” a popular saying by the end of World War I, was proving to be more than a cliché.

What accounts for the Greeks’ almost umbilical connection to the restaurant business? Over the years, as I’ve explored this question, I have encountered a variety of explanations. An early, playful comment came from Mario Christodoulides, the Greek Cypriot manager of a Queens, New York restaurant supply business. “When you first jump off the ship, the first thing you need is food. In order to eat, you have to work in a restaurant. You’re not going to start a plumbing business.” Perhaps it’s the Greek passion for food, their tradition of hospitality, that offers a clue, some surmise. Others speculate that the affection for the restaurant is rooted in memories of the old country’s kaffenion and taverna.

Their close-knit family, others suggest, is the bedrock of this ethnic business. Enlisting family members to work in the restaurant makes for trustworthy and industrious employees. Kinship connections stimulate a regular flow of workers to fill positions. Turning away needy relatives is “frowned upon,” Peter Scouras, owner of Buffalo’s Towne Restaurant, told Samantha Maziarz Christmann of the Buffalo News. “If your cousin comes over and you don’t give him a job, there’s something wrong with you.” Some of the recruits will learn the ropes and move on to start their own restaurants. Owners expect this. “When it’s time to go, it’s OK,” Pano Georgiadis, another Greek merchant commented to Christmann. “Nobody stays a cook forever.” Pano himself had left the Towne to found Pano’s restaurant. The seeds of future Greek eateries are sown in the old. As the cycle continues, restaurants multiply.

As I dug into the story of Troy’s Famous Lunchroom, I gained new insights into this Greek family niche. Her fellow ethnics are pervasive in the food world, Despina Nicholas, Scott’s cousin, told me. “Every Greek seems to have tried their hand in the restaurant business.” Her father Edward concurred, drawing on his own experience in and observations of the field. For Greeks new to America, “it’s one of the easiest businesses to get into.” The work is hard, but “if you can’t speak English, what job can you get?”

Steve Vasil, Scott’s father, saw his restaurant as the way to fulfill his immigrant dream. By working hard, he could not only send his kids to college, but also become an American. Steve was the “happiest man in the world” when he got his citizenship, Edward said. His lunch counter’s food reflected the same desire to belong. “I think he wanted to make something all American: Fast, delicious, and a good value,” Scott tells Saveur magazine’s Jamie Feldman.

Like many Greek merchants, Steve Vasil had a knack for identifying his customer’s tastes and catering to them. In the food world, Greek Americans stood out as purveyors of ample, familiar, and reasonably priced food. From lunchroom hot dogs to diner liver and onions, operators, especially in the early years, concentrated on the reassuring, rather than the exotic. As much as he loved his own cuisine, Steve was wary of offending his clientele by serving it. He “dared not open a place that sells Greek food,” Edward remarks.

The drive for economic independence, to be their own boss, impelled Steve, Scott, and so many other ambitious Greek ethnics. The restaurant business was their vehicle to do this. Even Scott, who received a degree in Industrial Engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, decided to succeed his father in the lunchroom rather than cash in on his credential. He did not want to suffer the restrictions of “corporate America,” cousin Despina observes. Scott was the “sort of person who prefers to have control.” The continued strength of the Greek restaurant business will depend on how many of the new generation follow his path.

Thanks to:

Despina Nicholas was very helpful in providing material about the Famous and in giving me the benefit of her growing knowledge about the history of Troy’s Greek community. Despina generously gave me a copy of the listings of Greek business sponsors from the 1942 St. Basil’s Church celebration program.

Scott Vasil took time out to talk to me about the Famous business, its story, and about Troy.

Edward Nicholas shared his insights into the role of Greeks in the restaurant business and provided me an absorbing account of the Greek immigrant experience.

Don Rittner, a historian of Troy, introduced me to tales of the city and recounted intriguing anecdotes about the lunchroom he loved.

Amy Halloran, the author of the book, The New Bread Basket, and a food activist, offered rich memories of the Famous Lunch through her writing and our conversation.