“Yes, We Have No Bananas”: It’s All Greek to Me

Roaming the web recently, I made a discovery, one that sheds light on the marriage between immigrants and fruit peddling. I had always assumed that the popular song, “Yes, We Have No Bananas,” was written about an Italian hawking fruit. I was wrong.

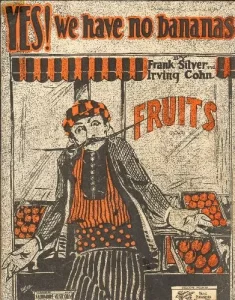

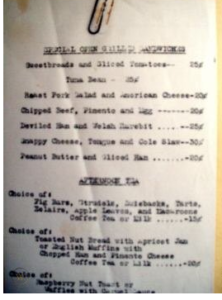

Sheet Music for “Yes, We Have No Bananas”

Thanks to Harry Karapalides and the Philly Greek-Style Blog for the revelation that the line came from a hit song released on March 23, 1933. The song, titled with that inimitable line, was composed by Frank Silver and Irving Cohn and later recorded by Benny Goodman, Jimmy Durante, Louis Prima, and

Spike Jones and his City Slickers. The peddler celebrated in the song was actually Greek.

Silver got the idea for the song from an encounter with a Greek fruit vendor. Silver, whose orchestra was playing at the Long Island Hotel, passed his stand every night. When the musician asked if he had bananas, his response was invariably, “Yessss, we have no bananas.” (Bananas were scarce because the Central American fruit then was riddled with disease.)

The line was so catchy that Silver felt impelled to write a song. “The jingle of his idiom haunted me,” the song writer recalled. The song’s first verse went like this:

There’s a fruit store on our street,

It’s run by a Greek,

And he keeps good things to eat,

But you should hear him speak!

When you ask him anything, he never answers “no.”

He just “yes”es you to death, and as he takes your dough,

He tells you,

Yes, we have no bananas.

Its chorus is memorable:

Yes, we have no bananas. We have-a no bananas today.

We’ve string beans, and onions, cabbageses and scallions,

And all sorts of fruit and say

We have an old fashioned to-mah-to. A Long Island po-tah-to,

But yes, we have no bananas. We have no bananas today.

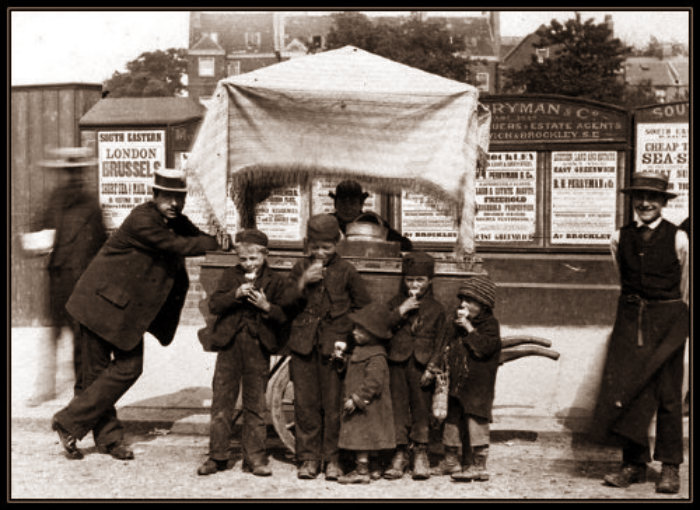

Street vending, especially peddling fruit, was a handy occupation for the immigrant greenhorn. According to some estimates, 2,000 Greeks in Chicago were peddling produce in 1911. Looking for help, a fruit merchant would take on a kinsman for a job that required little English and required short encounters with customers.

Greek Diner Owner

Peddling was also a stepping stone, a way to climb the job ladder. With savings, experience, and a sponsor, the vendor might improve his lot. He might move up, starting a small business—perhaps a hot dog stand, a lunchroom, or a shoeshine parlor. Many Greek newcomers chose this route.

Peter Bonduris, a New York City fruit peddler, funneled his kinsmen into jobs in Birmingham, Alabama, which had a large Greek enclave, after they had learned the ropes of his business.

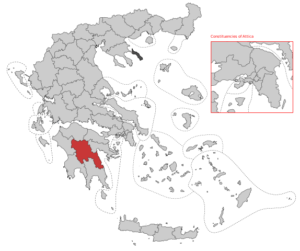

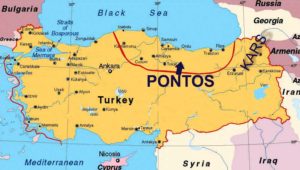

The Arcadian Region of Greece, Where the Village of Pelata Is Located

Over time, the new hand would pick up many of the habits, idiosyncrasies, and cultural nuances that could be learned in no other way. One of Peter Bonduris’s hires was John N. Bonduris, who came from Pelata, the same village in the Peloponnesus. John, who knew few words of English, had the same response to every customer’s question: “I don’t know and 10 cents a bunch.”

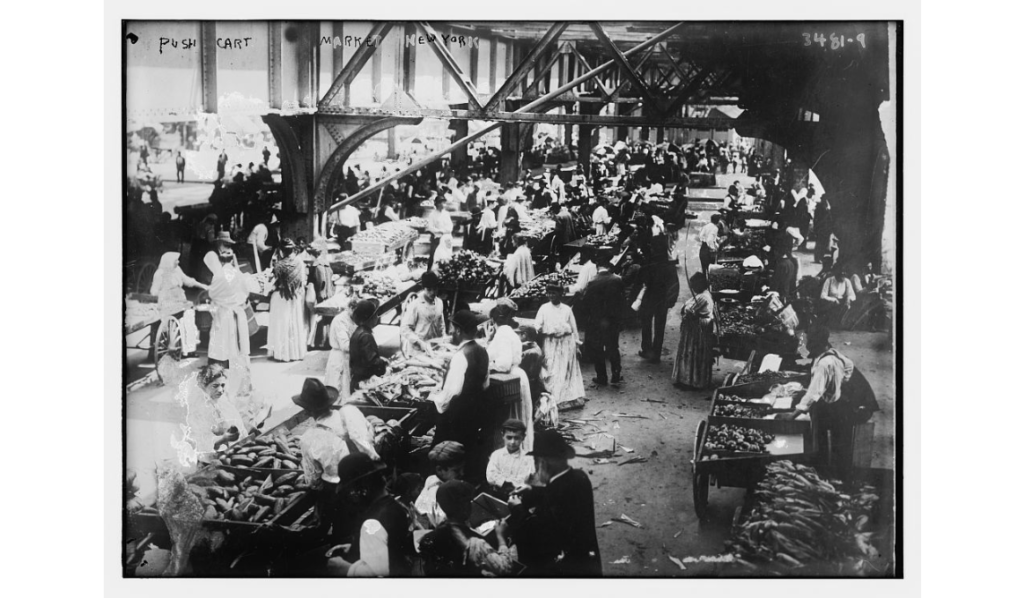

The Greek vendor was the purveyor of a fruit that was still novel and even forbidding. Some Americans worried that the fruit might be hard to digest and might upset their stomach. People also worried about a fruit sold on the street. The Literary Digest assured its readers that the fruit’s wrapper kept them “uncontaminated by dirt and germs, even if purchased from the pushcart in our congested streets.”

Push Cart Market, New York, Circa 1910-1915. Bain News Service

The immigrant peddler secured a place in American folklore. The mirth of “Yes, We Have No Bananas,” however, obscured the harshness of the vocation.

The peddler was often the victim of hostile prejudice. The Chicago Tribune heaped scorn on them: “Nearly every banana peddler in this city is a Greek. They herd together by the dozen, and have a head man who does all the buying, and usually drives a close bargain for a few banana bunches. The Greeks are of a very jealous disposition and believe all women are faithless. So they never marry in this country. They are filthy, shrewd, and of a low order intellectually. The profits of the day’s peddling are always divided equally among the company, and in this way they may be said to operate a small sized banana trust. They are born traders and carry on a profitable business, considering their daily expenses do not average more than 10 cents a day.”

Business groups pressed the city to stop the threat. In 1904, the Chicago Grocers Association urged the City Council to prohibit hawkers from peddling in alleys and streets.

Bananas

The Greeks also had to fend off rivals bent on stealing their business. In Chicago, Greeks and Italians battled for control: “… the Greeks have almost run the Italians out of the fruit business not only in a small retail way, but as wholesalers as well,” the Chicago Tribune declared in 1895. “As a result, there is a bitter feud between these two races, as deeply seated as the enmity that engendered the Graeco-Roman Wars.”

Despite the animosity, the immigrants were admired for their ambition and entrepreneurial drive: “… the Greek will not work at hard manual labor like digging sewers, carrying the hod, or building railways,” the same newspaper observed two years later. “He is either an artist or a merchant, generally the latter.”

Frustrated with their lowly status, the Greeks yearned for economic independence. These were not idle dreams. Many Greek street merchants pulled themselves up. In Chicago and other cities, they carved out a niche in the restaurant business. By 1913, according to sociologist Charles Moskos, there were at least 600 Greek-owned eateries in Chicago. Instead of peddling bananas, they were taking orders for coffee, hot dogs, and pie.

Lemon Tree, Very Pretty: Sicilian Immigrants and the Citrus Trade

It is thrilling to uncover nuggets buried in America’s ethnic history. Even before I started seriously writing about ethnic food, I was drawn to New Orleans. Its mix of cultures was fodder for my imagination. The port city I fixated on was an ensemble of African, Latin, French, and Creole flavors. In the beginning, these features, however exciting, were blurry. Their contours and details need filling in.

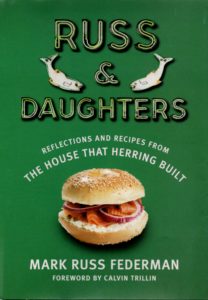

Muffuletta Sandwiches Being Prepared, with Their Signature Olive Relish

Calvin Trillin’s ode to New Orleans in the New Yorker, an account of his gastronomic expedition to the city, enticed me. My wife and I spent our honeymoon there, following Trillin’s lead and that of other writers. We snacked on red beans and rice at Buster Holmes’, a hole-in- the-wall in the French Quarter, celebrated by Trillin. We must have looked out of place when we asked for a menu and were given a barely legible list of items scrawled on butcher paper. On another day, I put on a required jacket and stood in line to dine at Galatoire’s, an institution of understated elegance, which paid homage to the city’s French and Creole culinary traditions. One late evening, we sat in the courtyard of the Napoleon House, a historic French Quarter establishment, savoring a muffuletta, one of New Orleans’s heralded sandwiches. We brought home a container of giardiniera, a mixture of olives, pickled carrots, celery, and tomatoes, from the Central Grocery Store. This relish frequently dressed the muffuletta.

For all this early immersion, I had just grazed the surface of the many layered city. When I began my investigation of America’s immigrant food, I chanced on a brief reference, a passing glance, in a New Orleans guidebook, to Progresso, a food business born in New Orleans. I knew Progresso mostly for its line of soups. I dug further and discovered that the company had been an early marketer of chickpeas, artichokes, roasted red peppers, and other Italian specialties that would later be displayed in the ethnic sections of supermarkets.

My curiosity whetted, I looked for more details. Progresso grew out of a peddling venture of Giuseppe Uddo, a young, adventurous Sicilian immigrant, who arrived in New Orleans in 1907 with his wife, Elenora. As a young boy, Giuseppe worked as a venditor, hawking olives and cheeses in his home town of Salemi and other nearby villages. After several false starts in New Orleans, he began vending cans of tomato paste, olives, and cheeses imported from his homeland. He carried them by horse and wagon to Italian truck farmers living on the outskirts of the city. Since Giuseppe refused to learn English, he depended on his horse, Sal, to guide him there. This was the beginning of Progresso, his son, Frank, told me. “The horse started the business.”

Uddo would team up with the Taorminos, another Sicilian clan who had opened an import business in New York City. The business marketed pomidori pelati (Italian peeled tomatoes), olives, and caponata, a favorite Sicilian appetizer, largely to small ethnic groceries. During World War II, Progresso shifted from imports to domestic production. The group bought a small factory in Vineland, in South Jersey, a heartland of Italian immigrant farmers. They canned and bottled roasted red peppers, hot cherry peppers, crushed tomatoes, and similar items. After the war, Progresso began searching for a year-round producer. They started making the country’s early ready-to-serve soups like minestrone and pasta e fagioli (pasta fazool), a mixture of broken-up pasta and beans in a tomato and salt pork sauce. Chain supermarkets now bought a larger share of the company’s products.

Map of Italy, with Sicily Shown in Red

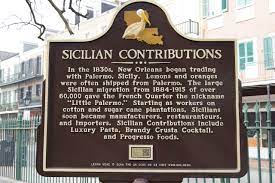

Uddo’s voyage to New Orleans was part of a larger migration that would reshape the Crescent City. By 1850, the town boasted the largest Italian community in America. The Italian population, with its predominantly Sicilian element, surged. Between 1880 and 1910, 50,000 of these immigrants streamed into New Orleans. Its semi-tropical climate, Mediterranean tempo, and Catholic traditions made them comfortable. They “recreated their world,” historian Joseph Logsdon observed, in this American Nice. The newcomers enhanced Creole cuisine with dishes like stuffed eggplant and artichokes and infused dishes with garlic and tomato sauce.

My image of New Orleans was also changing. This was not the town I had first encountered. I had largely missed the Sicilian influence in my early research. Why, I wondered, did this Sicilian bastion develop?

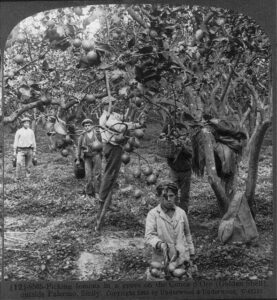

Sicilians Picking Lemons in a Grove Outside of Palermo, Sicily, at the End of the 19th Century

The boom in Sicilian immigration, I learned, was a result of the citrus trade, the transatlantic commerce in lemons and oranges. As early as the 1830s, the fruits were unloaded on the New Orleans levee across from the Mississippi River. Citrus, a much coveted commodity, was arriving in ships from the Sicilian ports of Palermo and Messina. Lemons bought and consumed in America before 1900, historian Justin A. Nystrom points out, were likely not grown in California but to have “come from Sicily and that a prosperous Sicilian immigrant had had something to do with it.”

I was familiar with the outlines of the trade from my earlier research. Nystrom’s book, Creole Italian, filled in its absorbing details. Nystrom tells the hidden story of the Sicilian passage to New Orleans. It was the pursuit of simple citrus fruit—not a quest for something grander, like riches, spices, or glory—that bound the Crescent City and Sicily together. The lemon not only propelled the trade but also the waves of Sicilian immigrants who settled in the port city.

The lemon was the “ideal trading perishable commodity,” historian Nystrom points out. The fruit could be picked while green and gradually ripen without spoiling on the long ocean voyage. Demand for the lemon in America was also strong. Countless recipes required lemon juice. Citrate, or citric acid, manufactured from the fruit, was indispensable to the canning process until a synthetic substitute was devised.

Anglo-American auction houses, Nystrom points out, controlled the early citrus business in New Orleans. It was not long, however, before savvy Sicilian merchants, capitalizing on their ties to the source of the fruit, began unseating the established traders.

After the Civil War, large cargoes of citrus were arriving in New Orleans, Nystrom notes. A load of fruit—6,855 boxes of lemons and 13,727 boxes of oranges—filled the ship Bessarabia, which docked in 1882. The Sicilian connection to the goods was obvious in the names of the commission merchants—Le Secco, Trapani, Randazzo—who ordered them. One Sicilian magnate, Angelo Cusimano, took the lion’s share of the fruit. Cusimano, who was also in the pasta business, purchased 5,849 boxes of lemons, 94 boxes of oranges, and 102 boxes of macaroni.

Other merchants concentrated on the retail side of the business. An 1860 ad for a grocery run by R. Tramontana, uncovered by Nystrom, advertised his stock. He was selling “creole oranges,” bananas, pineapples, along with other nuts and fruits.

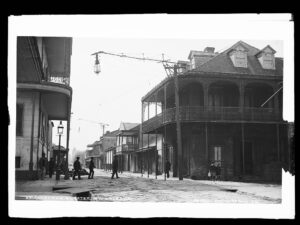

The New Orleans French Quarter at the End of the 19th Century

By 1890, the Sicilians had finally pushed aside the older merchant families in the trade. The ethnics now held sway over the importing, wholesaling, and retailing of the business. Profitable opportunities abounded. Peddlers selling fruit often moved to higher rungs on the ladder.

An Italian colony sprang up in New Orleans. Ships carried fruit, and sometimes passengers eager to make their way into the citrus business. Like the Uddo family, Sicilians clustered in an area near today’s French Market. In “little Palermo,” Italian purveyors were increasingly selling their wares at its stalls. “A riot of smells,” writer Richard Gambino observed, the market was fragrant with “musty vegetables, pungent fruits, sweet flowers.” The citrus trade put New Orleans on the map for Sicilians eager to strike out on their own. Ships loaded with fruit often carried passengers who wanted to try their luck in the burgeoning industry. Many of the Sicilians getting off the S.S. Utopia, scholar Jean Ann Scarpaci points out, toted small containers of lemons.

The ambition of the Sicilians stirred resentment among fearful locals. Joseph Shakespeare, the New Orleans mayor, castigated the immigrants in June of 1891: “They monopolize the fruit, oyster and fish trades and are nearly all peddlers, tinkers or cobblers…. They are filthy in their persons and homes and our epidemics nearly always break out in their quarter. They are without courage, honor, truth, pride, religion or any quality that goes to make a good citizen.”

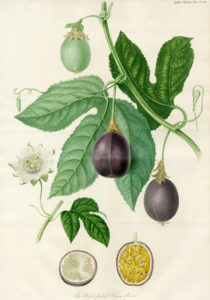

Lemons Growing on a Tree in Sicily

America’s partner in the citrus trade, Sicily, had been building a thriving lemon industry. Not native to Sicily, the lemon had actually begun its journey in the foothills of the Himalayas, where the trees grew, as one authority put it, “under the sheltering umbrellas of bigger trees.” The lemon was probably first cultivated in India. In the 9th century A.D., the Arabs on their imperial march colonized Sicily. They transplanted lemons and other crops like eggplant, spinach, and sugarcane to their possessions. The terrain in Sicily was hostile to a fruit that flourished in hot, steamy, and rainy conditions. Undaunted, ingenious Arab farmers set out to turn the arid land into a veritable oasis.

An intricate system of irrigation, based on aqueducts, ditches, and canals, channeled an abundant supply of water year-round for the soil. Author Helena Attlee describes the remarkable transformation of the land around the city of Palermo, the capital of the Arabs’ Italian colony, through the eyes of a Muslim traveler, John Hawqal, a Baghdad merchant. Spellbound, “he was moved by … the streams descending from the mountains to east and west, the water wheels lining their banks, and the land to either side of them planted with fruit trees, sugar cane, papyrus, and pumpkins.”

The lemon’s commercial breakthrough was hastened by the discovery of an English naval officer, James Lind. In a Treatise on the Scurvy, published in 1753, he argued that lemons were a cure for the illness, “the most effectual remedy for this distemper.” Fifty years later, the British navy required sailors to take an ounce of lemon juice sweetened with an ounce of sugar every day after two weeks at sea. Lord Nelson championed Sicily as a citrus source. “Some people remark,” Attlee notes, “that Nelson had transformed Sicily into a vast lemon juice factory.”

A contract to provide lemons to the British navy followed. Growers soon cast their eyes on America as a market for their produce. By 1857, over 19 million kilos of fruit, Attlee says, were shipped from Sicilian shores. In 1860, the wealth created by citrus farming in Sicily made it the most profitable agricultural business in Europe.

Marker Celebrating the Sicilian Contribution to New Orleans

Tempted by the riches to be gained, farmers with more modest wealth started investing in a crop that had once been largely the domain of aristocrats. Speculators spotted easy opportunities to take advantage of unwary citrus growers. Mafiosi organized a protection racket to rob growers worried by the costs of their risky endeavor. Gangsters offered to help, supplying water and erecting water pumps. For those who feared for the safety of their valuable crops, the crime lords provided guards. Of course, there was always a price to be paid.

Failure to pay pizzo, the protection money, was risky and sometimes fatal. Offenders were met with violence. It was “exercised openly, calmly, regularly and as part of the normal course of events,” according to an 1876 report cited by Attlee. The curtain of citrus barely concealed places where savagery prevailed. A visitor “will see the place where a garden owner who wanted to follow his own plans for renting out his lemon groves felt a bullet passing just above his head by way of friendly warning.” The report said “the perfume of orange and lemon blossom begins to smell like corpses.”

Shipping fruit across the Atlantic was expensive. Steam-powered shipping in the late 19th and early 20th centuries came to the industry’s rescue. Speedier, more fuel-efficient “lemon boats” now carried heftier cargoes. “The most valuable fruit,” Attlee points out, “was carefully arranged in wooden “American-style boxes and wrapped in colored tissue paper.” The citrus cargo between Sicily and the U.S. soared to new heights. Between 1892 and 1894, Nystrom notes, 400,000 boxes of citrus fruit were unloaded in New Orleans.

Many of the ships were now carrying fruit as well as large numbers of Italian immigrants bound for labor in the sugar cane fields outside New Orleans. Pliant hands, the peasants were replacing a recalcitrant black work force. Their work was back-breaking toil, cutting cane with their machetes during the day and, at night, grinding, boiling, and refining their product. Unlike earlier immigrants, many of whom were prominenti, notables and men of means, these recruits were typically downtrodden commoners. According to a press account, one shipload arriving in 1896 was “laden with 34,000 boxes of lemons and 600 tons of sulphur with a supplemental immigrant cargo of 121 souls.” The labor bosses, the padrones, who corralled the workers, were often one time fruit traders with close ties to the island.

Shipping companies synchronized their schedules with the sugar cane season in Louisiana. Boats left Sicilian ports just in time for them to unload passengers in early October for the zuccarata, the sugar harvest, which ran from October to January, the “immigrant season.” The citrus trade, Nystrom concludes, paved the way for the massive immigration of Sicilians: “The Sicily lemon, not only brought the original Sicilians to New Orleans but established the trade routes that nearly all of their subsequent countrymen followed.”

New Orleans’ Central Grocery Store, Known for Its Muffuletta Sandwich

The citrus bonanza would not last forever. Initially, there was no contest between the Sicilian lemon and the lemon grown in California. Vendors in a San Diego market in 1888, Nystrom notes, were almost uniformly dismissive of the American product. “The Sicily lemon is good, the California lemon is good—for nothing,” they told one observer. American growers did not surrender. They battled their Mediterranean rivals for supremacy in the market. A tough levy on imported lemons, the industry calculated, would knock the greedy Sicilians off their pedestal. The journal of the American Tariff League, Nystrom points out, sneered at the “competition.” “Among all the importers none are more persistent and vicious in their assaults on American industry than the firms, nearly all with Italian names, which are engaged in importing Sicily lemons.” By 1937, a crippling tariff on imported lemons achieved its objective. The California lemon had toppled the Sicilian.

The loss of the citrus business did not hinder the Sicilians. Businessmen, many of whom had prospered in the fruit trade, threw themselves into a new field, marketing tropical fruit from Central America. Two families, the Vaccaros and the D’Antonis led the way. They banded together, first opening a small general store in Baton Rouge and then, after a flood in 1897 destroyed it, embarking on a new venture. They transported oranges, picked down river, in luggers, small boats, to New Orleans, for sale at the French Market. The clans again suffered another misfortune. A ferocious winter storm devastated the orange trees on which the business depended.

They decided to change course. “If we are to achieve our ambitions in life, there is not much left for us here,” Joseph Vaccaro said to his son-in-law, Salvador D’Antoni. “I understand that there are coconuts and bananas in Honduras.”

Poster for the Standard Fruit Company

After some early forays to Honduras, they brought back coconuts, small loads of oranges, but only a few parcels of bananas. They soon got luckier, using steamboats to transport the more lucrative product, often carrying more than 200,000 banana stems a trip. The company rapidly captured the Honduras market. The enterprise expanded, acquiring and building its own railroad line, from the port to the fruit groves. The import trade took off. The small firm grew into a shipping colossus that became the Standard Fruit and Steamship Company in 1923.

The New Orleans elite, perhaps reluctantly, praised Standard’s success. The company helped make New Orleans the world’s largest importer of fruit in the early twentieth century. Over 600 notables gathered at the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans on October 5, 1925, to salute Standard’s contributions to the economy. St. Clair Adams, the president of the Louisiana Bar Association, lauded the owners for lifting New Orleans “out of the mud,” and transforming it into a “beehive of useful activity.” Once considered disreputable, Sicilians were at last given their due.

Notes

Justin A. Nystrom’s book, Creole Italian, was a treasure house of illuminating details about the New Orleans-Sicily connection. Helena Attlee recounts an absorbing history of the lemon, which is especially informative about the development of the fruit crop in Sicily. Jean Ann Scarpaci’s dissertation, Italian Immigrants in Louisiana’s Sugar Parishes, is a pioneering study of the ethnic labor force. My own book, The World on a Plate, tells the story of Progresso and examines the development of the Italian colony in New Orleans.

The Truth about Finocchio: The Wonders of Fennel

A field of fennel

A small plane, something like a crop duster, landed in a southern New Jersey field on a culinary mission. In 1975, New York Times food critic, Craig Claiborne, had decided to observe firsthand a plant that he had grown increasingly curious about. The writer had come to a farm owned by the Formisano family, whose four generations have been growing fennel since 1908. Gazing at the bountiful fields of this unique vegetable, prized by Italians and now gradually being discovered by inquisitive non-ethnics, Claiborne was captivated. The crop, he wrote in an article for the Times, was “caressed by a late autumn wind.” It “resembled a vast and undulating sea of green feathers.”

Claiborne watched intently as the workmen harvested the plant. “Ten workmen … are equipped with constantly sharpened carbon steel knives called cabbage knives. The fennel is lifted from the soil and, with one quick swoop of the knife to the underside of the plant, … the fennel is ready to be crated and labeled.” The family treated the visitor to a dish of sea bass baked in fennel. Claiborne relished the plate. He dubbed Ralph Formisano, the senior member of the family, the “fennel king.” The Times writer recounted his visit in the newspaper and his 1976 book, Claiborne’s Favorites. The Claiborne story paid dividends. “That put us on the map,” Ralph Formisano, the senior member of the family, told journalist Eileen Stilwell. (More on the Formisanos later.)

Claiborne had wanted to write about fennel after noticing how few Americans were acquainted with it. Writing in 1961, he spotted a customer mystified by an unusual item in a grocery’s vegetable counter:

It had a solid root end and its leaves were somewhat feathery. Timorously she asked a near-by clerk what it was and he answered “Fennel.” “How do you eat it?” she asked. “Raw.” It is regrettable that so few of the city’s inhabitants know of the vegetable and even fewer know its virtues.

A fennel bulb with stalks and fronds untrimmed.

The variety of the fennel plant the Formisanos grow was first cultivated in Florence, Italy in the 17th Century. Florence fennel, the type most shoppers are familiar with, is distinguished by feathery fronds that spill out from its celery-like stalks and by the buxom bulb at its base. This feature makes it look like “pregnant celery,” as writer Maggie Stuckey describes it.

A versatile ingredient, fennel lends itself to a variety of tasty dishes. It goes particularly well with fish, as Claiborne discovered. It can be braised, steamed, or grilled. Paired with olives and oranges, and dressed with olive oil, fennel makes a piquant salad. Laced with fennel seeds, sausages and salamis are invigorated.

Fennel flowering.

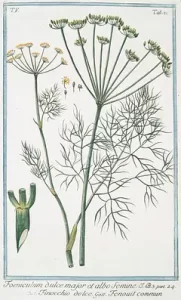

Native to the Mediterranean, fennel, like carrot’s ancestor Queen Anne’s Lace, grows wild in meadows and country roads. A cluster of brilliant yellow flowers, which yield aromatic seeds, form a parasol, or umbel, over the plant. Fennel shares this umbrella with other members of the umbelliferae family, like coriander, dill, and anise. Fennel, like some of its relatives, is infused with anethiole, an oil that produces a licorice-like fragrance.

Of ancient lineage, the plant was dear to the Greeks and Romans. Its name derives from the Latin foeniculum, or fresh hay, probably because of fennel’s lively scent. The Romans delighted in young shoots marinated in brine and vinegar. Fennel seeds were sprinkled in cakes and bread. Its licorice flavor, the Roman naturalist Pliny points out, was excellent for “seasoning a great many dishes.”

In the ancient world, the fragrant plant was more than a valued spice. Fennel, it was felt, made you lean and fit. The Greek name for the plant, marathon, has its roots in the word, maraino, to “grow thin.” Marathon, the location of the celebrated battle between the Greeks and Persians, food scholar Raymond Sokolov explains, got its name from the plant, which covered its fields.

Fennel plants.

Fennel was reputed to help soothe the stomach. Eating a stalk of fennel, Socrates recommended, could alleviate the upset. In India, fennel seeds were prized for similar reasons. After eating, many Indians today chew the seeds to settle their insides.

Fennel, it was claimed, was also especially helpful for the eyes. It sharpened eyesight and cured blindness, Pliny wrote. Snakes, he observed, rubbed up against the plant after shedding their skin. They were trying, he surmised, to regain their sight by getting the plant’s juice in their eyes.

In later years, medical commentators echoed Greek and Roman lore. “Both the seeds, roots, and leaves of our Garden fennel are much useful in drinks and broth for those who have grown fat,” the 17th Century English naturalist, William Cole, wrote.

In a similar vein, 17th Century English gastronomer John Evelyn urged his readers to eat the vegetable peeled like celery. The benefits: it “expels wind, sharpens the sight, and recreates the brain.”

The modern pairing of fennel with fish has earlier antecedents. Europeans, herbal scholar Maude Grieve observed, enjoyed it as a “condiment to accompany salt fish during Lent.” Botanist John Parkinson praised fennel’s gifts to both “meal and medicine.” It “helpeth to digest the crude quality of fish and other viscous meats.”

Fennel seeds.

Chewing fennel seeds also alleviated hunger, according to other authorities. A godsend to the poor, English garden historian Alicia Amherst pointed out, the destitute considered fennel as “a relish to unpalatable food.” In North America, Puritans turned to “meeting seeds,” dill and fennel, to endure long sermons and aching stomachs at church.

In Italy, the name for the plant, finocchio, recalled the ancients’ trust in its vision improving qualities. Food historian Raymond Sokolov offers a translation of the word. It is a “contraction” for “dainty eye.” The word, he says, gradually became Italian slang for “homosexual.” Trading on the slang term, a late night club in San Francisco’s North Beach, famous for its female impersonators, called itself Finocchios.

Finocchio was linked to flattery and dissembling. The expression, “dare finocchio,” means to “give fennel” or flatter.

In Shakespeare’s England, fennel took on a similar allusion. In playwright Ben Johnson’s play, The Case Altered, Christopher and the Count have this exchange:

Christopher: No, my good lord.

Count: Your good lord! Oh! How this smells of fennel!

The Italians grew increasingly passionate about this fragrant vegetable. Giacomo Castelvetro, the 17th Century culinary writer, spoke of the verve it brought to social gatherings:

We preserve quantities of fresh fennel in good white wine vinegar and eat in summer and in winter when offering drinks to friends between meals. We also serve this pickle with fruit in special occasions, when fresh fennel is not to be had.

Fennel’s fame spread throughout the English-speaking world. In the U.S., the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote rapturously about it:

Above the lowly plants it towers,

The fennel, with its yellow flowers,

And in an earlier age than ours

Was gifted with the wondrous powers

Lost vision to restore.

It gave new strength, and fearless mood.

18th Century illustration of sweet fennel.

In America, Jefferson was an early admirer of the plant. Thomas Appleton, an American consul in Naples, Italy, sent the Virginia planter some fennel seeds in 1834. Thomas Jefferson wrote a lyrical letter in response:

[The] fennel is, beyond every other vegetable, delicious. It greatly resembles in appearance the largest size celery, perfectly white, and there is no vegetable that equals it in flavor. It is eaten at dessert, crude (raw), and with or without, dry salt. Indeed, I preferred it to every other vegetable or to any fruit.

Still, for many years, fennel was unknown to most Americans. If recognized at all, it was regarded as an ethnic vegetable, the province of Italians. Before it graced sophisticated dining tables, it was grown by Italian immigrant farmers. In the early 1900s, Giovanni Formisano, one such pioneer, left his village near Naples, where his family grew the plant. Arriving in New York City, he landed a job on the railroad. He labored long hours for a dollar a day, his grandson John Formisano, Sr. recalls. Tiring of the toil, he searched for more fulfilling work. Pursuing his love for tilling the soil, he was a hired hand for several New Jersey farmers. By 1908, he had saved enough from his meager earnings to buy his own piece of land in Carlstadt, a North Jersey town.

Label for Formisano Farms.

Drawing on childhood memories of his homeland, Giovanni started cultivating Swiss chard, romaine lettuce, celery, and, of course, fennel, to name a few of his crops. He brought his goods to sell at the 14th Street market in Manhattan. As John tells it, Giovanni drove his horse and wagon to Hoboken, New Jersey, where he took the ferry to the city. The wagon was loaded with barrels of cabbage and flats of fennel stacked three feet high, crammed in with other vegetables. His prime customers were small, ethnic vendors who arrived at the market with their pushcarts. Each group had its own preferences—Germans for cabbage, Italians for escarole, dandelions, endives, and fennel. Some shoppers came home with bushelfuls of plum tomatoes. After an exhausting day, John says, Giovanni would take the ferry back and quickly fall asleep in his wagon, trusting his horse to get him home. Over time, Giovanni sold his wares at markets in Newark, Paterson, and other cities.

As his business prospered, the budding farmer could afford new vehicles. A tractor replaced the horse and wagon. In the late ’twenties, he bought a Mack truck and a Model T. His repertoire expanded. During the ’twenties, John points out, he started selling basil for a quarter a bunch. The plant, loved by Italians, came in one pound coffee cans.

A trimmed bulb of fennel.

Formisano’s, which moved first to Moonachie in North Jersey and then to its present location in Buena, a South Jersey town, is in the heartland of Italian farmers. Early settlers from southern Italy got their start as strawberry or raspberry pickers or as railroad workers in the late 19th Century. Many immigrants also took jobs as farm laborers. Whatever route they took, their goal was to save enough to own their own land. They were not stymied by the sandy soil of the Pinelands region of South Jersey. As older farmers retired, Italians replaced them. Two substantial colonies of the immigrants sprang up, one in Vineland, the other in Hammonton, two towns not far from the Formisano farm.

Emily Meade, a sociologist and mother of anthropologist Margaret Mead, visited Hammonton in 1907 and marveled at the novel produce the farmers were harvesting: “Italians have popularized the sweet pepper and introduced … a peculiarly shaped squash, okra, Italian greens and various kinds of mint.” Hammonton often claims to be the “most Italian” community in the U.S. (Emily Meade’s name is often spelled this way in publications, but in other instances it is spelled Mead.)

Most of the farmers in the area are still of Italian heritage. The people in Vineland keep their culture alive with an annual Spring festival featuring a Dandelion dinner where an array of foods and drinks made from the plant are enjoyed. The menu might include a salad with dandelion greens, dandelion ravioli, and ice cream with dandelion brandy. The town, where dandelion wine is a not uncommon refreshment, calls itself the “Dandelion Capital of the World.”

John Formisano with fennel ready to go to market.

Formisano Farms, one of the oldest in the area, has burgeoned into a full-scale enterprise purveying a wide variety of produce. Food brokers and wholesalers, supermarket chains, and gourmet shops snap up their wares. “We don’t have to knock on doors anymore. We’ve got enough business,” John Formisano, Sr. who grew up chopping celery in the fields, told reporter Stilwell.

Formisano’s, Richard Vanvranken, the Rutgers University agricultural extension director for Atlantic County, observes, is a groundbreaking enterprise, “introducing specialty herbs and fresh market herbs to the Vineland region of South Jersey.” “When the Formisanos arrived, production in the region was mostly of summer/fall staples like peppers, tomatoes, sweet corn and sweet potatoes. Spring and fall greens opened new markets and extended the production season for the region’s small farmers.”

Formisano’s accommodates both older generation ethnics and customers with more contemporary tastes. To please stalwart Italians, the farm offers them escarole, dandelions, and endives. Some of these buyers ask for finocchio, not fennel.

Always alert to culinary trends, “they like to try anything new and different to open new markets,” Vanvranken points out. Parsley, he adds, was a “multi-million dollar crop when I arrived forty years ago … but by the late ‘80s, cilantro, that no one had a clue about, was being grown just as much.” Cilantro joined basil and arugula as a Formisano staple.

Their renowned fennel crop has its peak season during the fall. The greatest demand is from September through Thanksgiving and sometimes, if it isn’t too cold, till Christmas. During this period, the tempo at the farm is especially brisk. That is “when it moves,” John Formisano, Sr. says.

Assorted Formisano produce.

Never complacent, the partners are keenly attuned to the changing tastes new immigrants are bringing to the marketplace. Indian shopkeepers who first came looking for eggplant began seeking more unusual plants. Fenugreek, or methi, was at the top of the list for the “Indian people,” John notes. The herb, used in a variety of ways in the country’s regional cuisines, is especially treasured for its leaf. When harvested, John points out, fenugreek should only be picked when it “sports a nice green leaf.”

The Formisanos rode the wave of fennel’s rising popularity. Once considered exotic or simply as an Italian delicacy, it now has cachet. Upmarket hotels and restaurants are enlivening their menus with fennel dishes. The Atlantic City Borgata Hotel, 30 miles away, began ordering fennel and other unique items like candy-striped beets and Sicilian oregano from them. The Borgata’s dining room created a fennel tempura, sprinkled with lime juice and sea salt.

However, there is still more marketing to be done. The uninitiated sometimes confuse fennel with anise, which has a somewhat similar taste. To prevent confusion, the Formisanos label some cartons of fennel as “anise.”

Fennel is savored in the Formisano household. John, Sr.’s wife Mary often makes a carrot and fennel soup. More than anything, John enjoys the simple pleasure of a snack Italians call pentimento. He nibbles slices of fennel cut from the bulb, dipped in olive oil. It’s something to relish, he says, “while watching a ballgame.”

Acknowledgments

Anita Formisano, who runs the Formisano office, was very helpful. I am grateful to John Formisano, Sr. for taking time away from his labors to talk with me. Thanks to Richard Vanvranken, the Rutgers Agricultural Extension Director for Atlantic County for facilitating my introduction to Mr. Formisano and for sharing with me his insights and observations about farming in the Garden State.

Feeding a Boom Town: Greek Immigrants in Birmingham, Alabama

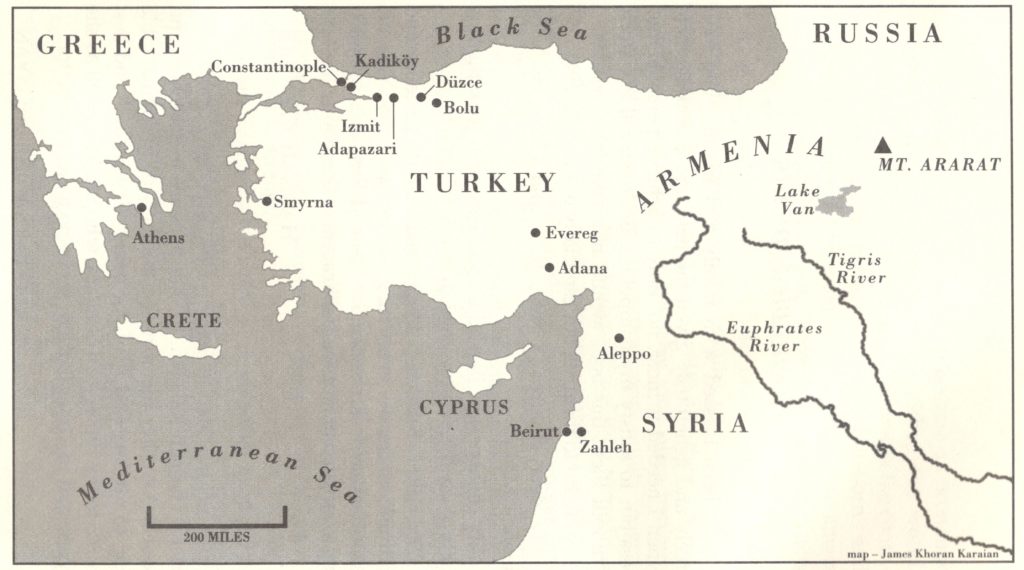

The Peloponnesian peninsula, in red, at the south of Greece

A young man from a small village in Greece’s rugged Peloponnesian peninsula set out on a journey in 1902. The 14-year-old Tom Bonduris was on a trek to improve his fortunes. Opportunities were few in Peleta, a mountainous community that sat on a plateau 2300 feet above sea level. “A farming village of traditional stone houses,” writer Niki Sepsas pictures it, it was “dotted with stately fir and cedar trees…. The pastoral setting was peaceful and idyllic.” For all its beauty, Peleta was a place where farmers labored to eke out a living from the soil. Farmers milled grain with the help of their horses and donkeys. Many owned goats and sheep. Wild greens were dried and saved to be consumed during the winter.

When Sam Bonduris, Tom’s nephew, visited Peleta many years later, he was struck by the harshness of the place. This village, once part of the Ottoman Empire, was “impoverished.” In 1971, Sam said, Peleta was still without electricity.

The village of Peleta, Greece

Peleta was blessed with a tight-knit family network. It was almost “tribal,” Sam observed. Tom Bonduris relied on these kinship ties during his journey. In New York City, Tom’s destination, the helping hand of a family member eased his arrival.

Tom got off the boat at Ellis Island and soon joined an uncle, Peter T. Bonduris, who ran a fruit stand in Manhattan. Peter had left Peleta in 1895 and took up a business that was a foothold for many early Greek immigrants. Peter put Tom to work. Part of the job’s appeal was that it required little English. John N. Bonduris, Tom’s first cousin, whom Peter took under his wing a few years later, discovered that hawking fruit demanded just a few words. He was taught to give the same answer to every customer’s question. His stock response, Sam says, was “I don’t know and 10 cents a bunch.”

After two years of learning the ropes at the fruit stand, Tom went home to Greece after catching pneumonia. Returning to America in 1906, he disembarked in Savannah, Georgia. He left there for Birmingham, Alabama for reasons that are somewhat murky. But, as Sam Bonduris guesses, his uncle had probably heard through the family grapevine that Birmingham was “booming” and that some Greeks, possibly relatives, had already settled there. That was enough enticement.

Tom’s journey took an intriguing twist. He began baking pies at a Greek-owned restaurant in Birmingham. A year later, Tom would found the Bright Star Café, now a 100-year-old establishment and the longest continuous restaurant in Alabama. The Bright Star is a monument, a testament to the achievement of Greek immigrants in building a flourishing food industry in the Birmingham area. (More about Tom later.)

Birmingham might seem an unlikely place for Greek immigrants to settle. Bonduris had actually arrived in a city where a Greek colony was already springing up. The deep South town was a community, no longer slumbering, but one energized by a budding industrialism that was attracting newcomers. In 1900, historian of Birmingham’s Greek immigrants Niki Sepsas notes, there were already 100 Hellenic pioneers. In ten years, the number would rise to 500.

In his book, Hellenic Heartbeat in the Deep South, Sepsas points to George Cassimus, a Greek seaman, as the first arrival. Cassimus had been working for the British navy running guns for the Confederacy out of the Alabama port of Mobile. After the war, George began looking for new pursuits. He moved to Birmingham in 1884, where he “found a brash young boomtown barely thirteen years old that was developing around what had just been a mud-spattered railroad crossing,” Sepsas writes.

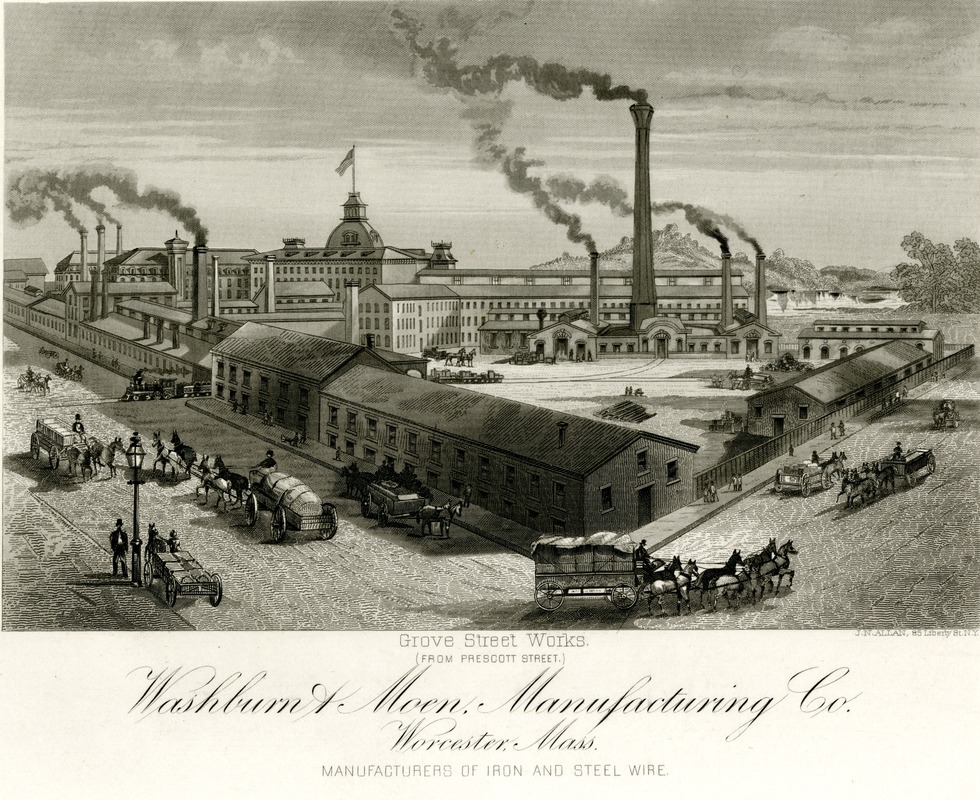

Birmingham, Alabama in 1885

Birmingham, named for England’s industrial powerhouse, was in the midst of a radical transformation, Sepsas says. “By the early 1870s … glowing blast furnaces had begun lighting the night sky, and coal and iron mines were offering employment to hundreds of former plantation workers and immigrants from other states and many foreign countries.”

Cassimus took a job with the city’s fire department. He put aside enough money to start a short-order eatery. Details about the business are thin, although the enterprise was known as a “fish eating place.”

Greek immigration to Birmingham was part of a larger stream of voyagers uprooted by economic hard times and propelled by the limited opportunities of their villages. Many were single men from farming families, often from the Peloponnesus. Initially, they envisioned their journey as a short-term sojourn, only long enough to accumulate a nest egg to bring home.

Some were motivated to earn money to fulfill family obligations. One such immigrant was Triantaffillos Balabanos, who left his village of Tsitalia in the early 1900s. He booked passage on the steamship Athinai, which was bound for New York from the Greek port of Piraeus. After a 13-day trip, he disembarked on September 29, 1909. He was not greeted with a welcome mat. According to writer Philip Ratliff, officials required him to swear that he could read, did not practice polygamy, and was not an anarchist. He listed his destination as the Reliance Hotel in Birmingham, one of whose owners was a kinsman, T. N. Balabanos.

Triantaffillos was on a mission. He wanted to work long enough to pay for a dowry for each of his five daughters. He returned home five times with the funds to meet his goal. He made money in restaurant jobs and at his relative’s hotel.

Triantaffillos, who went home in 1939 and never returned, left a legacy. George Sarris, a Birmingham food titan who founded the Fish Market food business, was his great grandson. Generations of Greeks in the restaurant industry carried the Sarris name.

“You weren’t here to change

the culture of America. You

were here to make a living.”

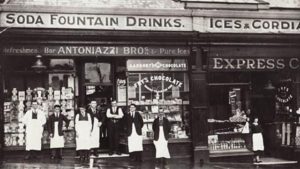

Every immigrant group in Birmingham followed a different path. The Italians captured the grocery business while the Jews, writer Sepsas observes, gravitated to “mercantile” occupations, like dry goods. In the early days, the Greeks ran a host of enterprises, lunchrooms, soda fountains, candy shops, meat markets.

Greeks shared a disdain for the factory jobs that abounded in the “Pittsburgh of the South.” Although some signed on as hired hands in factories, they were reluctant recruits. “You’re not going to work in steel mills or mines” over the long term, Sepsas, who himself had worked in several Greek hot dog businesses, observes. The Greeks dreamed of economic independence, of self-employment.

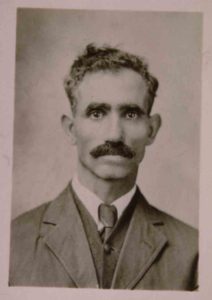

Greek immigrant and factory worker Constantinos Sfakianos

Industrial labor was not only grueling but dangerous. Constantinos Nicholas Sfakianos suffered through a perilous job. In 1907, the immigrant joined ten other countrymen at a steel plant in Ensley, a community in greater Birmingham. In an interview with a Birmingham research group, he recounted his ordeal:

“I stayed on that job fifty-three years, painting smoke stacks. There were no lights to work by so we burned wood for light for ten or fifteen years.

“I lost my hand in that plant in 1941. A crane in the blast furnace crossed my hand. Cut part of it right off. After six months, I went back to work. The company, the big boss liked me. He knew me because I worked there all my life.” (Source hereafter referred to as Patrida.)

Fruit vending was an early launching pad for the settlers. It was a good fit. Little English was required. Moreover, Sepsas points out, the immigrants had worked on farms back home and possessed a “pretty good knowledge of fruits and vegetables.” Sofia Petrou, a scholar who studied Birmingham’s Greek colony, suggests another inducement:

“The majority of the early Greek immigrants in Birmingham found a lucrative business in sidewalk fruit stands …. This type of small business allowed the Greek immigrant to assert the economic independence that had eluded him in Greece. All he needed was a small capital investment, usually acquired from his former homeland, and knowledge of the product he was selling.”

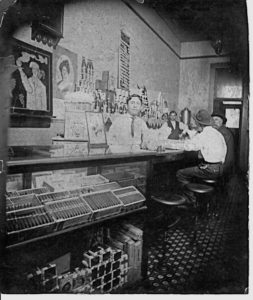

The immigrants’ commercial instincts served them well. In 1902, the Birmingham newspaper, The Herald, reported that the Greeks had acquired a monopoly of the fruit business. Christine Grammas describes one such operation run by her father, Sam Derzis:

Sam Derzis and his family

“My daddy’s stand didn’t have a front door. It had counters with fruit stacked up just as pretty as you could see and then in the back he had an ice box where he would slice the watermelons and sell them by the slice. On one side he had candy counters where he sold Hershey bars, peanut brittle, and coconut crisp—and there was a cigar counter.” (Patrida)

Vending fruit might lead to more profitable ventures. Alex Kontos, who arrived in Birmingham in 1889, started out selling fruit from his horse and wagon. Later, he teamed up with a Mobile, Alabama wholesaler to market bananas, which were being shipped to the port. He introduced the then-strange, exotic fruit to Birmingham. Transporting bananas in box cars to the city, the “Banana King” soon controlled the sales of the fruit. Kontos later parlayed his enterprise into a full produce wholesale business.

The fruit dealers’ success bred resentment in the city’s business establishment. The vendors posed a public health threat, some claimed. One vehement opponent of the ethnic trade compared the Greeks to “Chinamen.” “They do not build up a town but send their earnings to the old country.” His tirade continued: “Which should we encourage, our home merchants … or these foreigners? It is a case of choosing between John Smith and Harry Williams or Demosthenes, Thucydides and Aristotle.” (Patrida) The Greek merchants won the fight. In a vote of 13-4, the city council permitted the vendors to continue their sidewalk trade.

The restaurant business, as it did in small towns and cities across America, exerted a strong attraction for Birmingham’s Greeks. It was their niche of choice. The savvy entrepreneurs spotted a gap in the market and decided to move quickly to fill it. The growing urban population hungered for inexpensive, quick, and filling fare. “Those industrial workers, many of whom arrived without spouses or children, clamored to wolf down lunch break sandwiches from portable canteens, to dine in cafés, to drink and carouse in taverns,” Southern food historian John T. Edge explains. The bold immigrants ventured into a field where old-line merchants were hesitant to tread.

In the process, the Greeks built a moderately priced food industry, one which had not previously existed. The culinary transformation of Birmingham was stunning. In 1912, a traveling salesman, Sepsas notes, heaped praise on the immigrants’ contribution: “The Greek-owned restaurant relieved a well-nigh intolerable gastronomical situation.”

Over the years, the Greeks in Birmingham plunged into a wide variety of pursuits. The hot dog business was an early favorite. In 1919, Tom Kandilas opened what was reputed to be the first or one of the earliest hot dog stands. Tom, who had previously worked in the fruit and vegetable trade, promoted the “Birmingham dog.” Tom’s Coneys, his shop, sold a “hot beef” frank, similar to the one that Greek vendors hawked in many locales across the country. It was spicy and was topped with mustard, onions, and sauerkraut. The piece de resistance of the dog was the “special sauce,” whose secret ingredients Greek merchants guarded zealously. It was probably flavored with cinnamon, allspice, and other tangy Greek spices.

The stories of colorful ethnic vendors became part of Birmingham lore. Emily Brown, a local food writer, relates one such tale about Kandilas. As his granddaughter, Tasia, tells it, Tom kept a half pint of liquor next to his cash register. For special customers, he might pour a bit into their coke bottles.

The roster of hot dog peddlers in Birmingham included such names as Pasisis, Koutroulakis, Graphos, and Gerontakis. “Forty years ago, hot dog merchant Lee Pantazis told writer Bob Carlton, “you couldn’t throw a stone without hitting a Greek hot dog stand, whether it was a little restaurant like this or a cart on the side of the road.”

The business was well suited for early Greek immigrants. “You have to remember,” Birmingham restaurateur George C. Sarris told an interviewer, “when [the Greek immigrants] first came here, they had no language, no nothing. Hot dogs were easy. There was little cooking. A hot dog and a sauce, that’s pretty much it.”

Other innovators branched into a great variety of enterprises. During the decades, Greeks launched barbecue, “meat and three” (more about that later), and even white tablecloth dining rooms. Blanketing the city with their eateries, Greeks came to dominate Birmingham’s food business. “We laugh and say, if it hadn’t been for the Greeks in the ’60s and ’70s, the people of Birmingham would have starved,” Tim Hontzas, owner of Johnny’s restaurant, told correspondent Bryan Roof.

The restaurant owners had a keen feel for the tastes of their customers. In the beginning, they played down their heritage and instead offered familiar, inoffensive dishes. “You didn’t see Greek people serving spanakopita and tiropita and keftedes and this and that,” Hontzas explained to journalist Georgia Clarke. “They served barbecue and they served hot dogs and they served meat and three—Southern cuisine.”

On the road to success, the Greek restaurant journey could sometimes be a rocky one. Birmingham natives might cast a suspicious look or toss an epithet at the “aliens.” Some might sneer at the “dagoes,” an offensive term usually applied to Italians. “Greeks were sometimes asked to sit in the black sections of restaurant establishments and were discouraged from housing in certain parts of Birmingham,” historian Petrou points out.

Greeks often modified or changed their names to appear less conspicuous. Writer Sepsas tells the story of a Greek immigrant, Chris Mitchell, who felt impelled to do this: “My father, Nicholas Mitchinikos, came to America in 1898 and settled in Birmingham. He was twelve years old at the time. A man took him to find work. ‘No speak English,’ my father said. The employer asked him his name and he answered ‘Mitchinikos.’ ‘Too hard,’ the man replied. ‘Let’s make it Mitchell.’ That became the family name.”

The xenophobic climate strengthened the already powerful determination of these immigrants to earn acceptance and recognition. For restaurant owners, the food business became a pathway to belonging and moving up in a foreign land.

For Greeks with an entrepreneurial drive, there was also plenty of fertile soil to plough near Birmingham. After a year in Birmingham, the pioneering Greek immigrant Tom Bonduris was restless. Eager to work for himself, he struck out for Bessemer, a town 15 miles west of Birmingham. The boom town was the brainchild of Henry Fairchild DeBardeleben, a go-getter born on a cotton farm, who had tried his hand as a teamster boss, a lumberyard foreman, and in other occupations. With two partners, he began laying plans to create a city that would take advantage of the region’s rich veins of coal, iron ore, and limestone.

The visionary imagined a city built around eight blast furnaces and fed by eight railway lines. He laid out his boundless dream, Sepsis notes, to the Birmingham Age journal in 1886: “We are going to build a city solid from the bottom and establish it on a rock financial basis. No stockholder will be allowed in who can’t make smoke. It will take $100,000 to come in and the man who can make the most smoke can have the most stock.”

A year later DeBardeleben’s dreams were realized. Originally called Brooklyn, the city’s name was aptly changed to Bessemer, after the British inventor of the process of transforming molten iron into steel. The Bessemer technique, a boon to the city’s industry, made steel production more efficient and less costly. Before long, Bessemer would burgeon, rising to become the state’s fourth largest city by 1890. The city now throbbed with blast furnaces, iron works, and steel mills.

For a young man with his eye on the main chance like Tom Bonduris, Bessemer offered alluring possibilities. The teeming city was drawing miners, mill workers, and office employees, all potential customers for a lunchroom. Several trains roared through the city each day, bursting with miners, sometimes hanging on the side.

The Bright Star’s neon sign

Tom opened the Bright Star Café in 1907. A neon sign, star-shaped, with the business’s name proclaimed the young man’s aspirations. Tom must have been thrilled about this venture. “He came to this country as a young thing. He worked as a waiter,” future Bright Star owner Jimmy Koikos told Amy Evans from the Southern Foodways Alliance (hereafter as SFA). “And he heard about Bessemer being the young, mining, progressive town, so he came here and … opened up the Bright Star.”

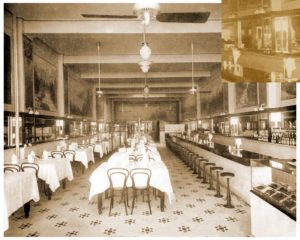

The Bright Star was conceived as a working people’s café. The setting was simple, functional. A horseshoe-shaped bar sat probably 35 patrons on its stools. There were no tables or booths. The counter contained a glass case full of cigar boxes.

During its infancy, the Bright Star fed its customers basic unadorned fare. “Blue collar workers,” historian Sepsas says, were its bread and butter. To serve workers as they came off their shifts, the eatery ran 24 hours a day. The atmosphere of the Bright Star mirrored that of the city. “The town of Bessemer was booming,” Jimmy Koikos said in an oral history. “It was just people coming from mining towns—coffee, donuts, chili.” “Maybe about … four-thirty or five [in the morning] they would clean up and getget ready. And then there’d come breakfast and people going.” (SFA)

As the business caught on, the menu evolved. Honoring Southern tradition, the Bright Star began offering a “meat and three” or a “plate lunch,” as it was originally called. For hard-to-beat prices, patrons could choose among chicken-fried steak, catfish, or other main dishes and select three from an array of fresh vegetables like okra, pole beans, and fried green tomatoes. Long before “farm to table” became a fashionable culinary trend, Greek merchants, many of whom came from rural families themselves, were purveyors of the country food that Southerners cherished.

Counter in the Bright Star Cafe

Tommy Bonduris, another member of the restaurant clan, who worked as a bus boy at the Bright Star, described its fare: “A plate lunch at the restaurant in those days went for twenty-five cents. You got meat, three vegetables, a dessert and a drink. Coffee and doughnuts were a nickel.”

The “meat and three,” the eminent Southern food writer John T. Edge told journalist Adam Rhew, was “the foundational Southern meal.” This plate, the “bedrock of Southern culture,” had deeper roots than either fried chicken or barbecue. Country migrants to the city, Edge observes, brought their culinary affections with them. “As the Southern worker transitioned from farm to city, you see this meal arise…. It was food for people who plowed the back forty (side of the farm) …. Reinterpreted for people who work at desks and in factories, catching lunch breaks in the city instead of returning home for lunch.”

Serving this plate paid dividends. “Southern food was a way to assimilate,” Beba Touloupis, an owner of Ted’s Restaurant in Birmingham, told a trade publication. Pete Hontzas, who helped run Niki’s, another eatery in the city, offered a blunter explanation for this practice. “They did serve some Greek dishes, but you had to serve what people would buy,” he explained to writer Jennifer Kornegay. “You weren’t here to change the culture of America. You were here to make a living.”

The Bright Star went through several incarnations, moving from location to location as the restaurant grew. Its fourth and final address in 1915 was in the heart of Bessemer’s thriving central business district. The choice of the site was deliberate. Hoping that the Bright Star would be imbued with the city’s vibrant energy, Tom Bonduris placed it in the center of commerce.

Inside the Bright Star Cafe

The Bright Star’s decor enhanced its appeal. Ceiling fans, hand-tiled floors, mirrored and marble walls, and marble countertops were highlights of the establishment. It had the feel, some observers felt, of a French café in New Orleans.

Hand-painted murals done by an itinerant German artist stood out. The story behind these paintings is part of Bright Star lore. As later owner of the restaurant Jimmy Koikos tells it, this footloose artist was “kind of just really like a wino, but he had talent.” Owner Tom Bonduris liked his work. “So he painted a European thing. And then he painted these murals one by one. Put them up. Then they fed him and wined him and he just wandered on through. He never dreamed they’d be up ninety years later.”

The interviewer probed further. “So did he just do it for trade?” “For trade and maybe we talk—talked to Mr. Bonduris a little bit—maybe a little money,” Jimmy said. (SFA)

Years later, seeing the “nicotine-patinaed murals” and eating a meal at the Bright Star was a moving experience for writer John Edge. He “realized that restaurant is its own kind of working man’s cathedral,” he told journalist Bob Carlton. “It’s an impressive place in which to sit, and yet is still mundane enough for people to have lunch there.”

(To Be Continued)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS & THANKS

I am indebted to Niki Sepsas, a Birmingham-based writer, for sharing his extensive knowledge of the area’s Greek community. Sepsas’s books, Hellenic Heartbeat in the Deep South and A Centennial Celebration of the Bright Star Restaurant, whose contents he assembled for the business, are invaluable guides to the history of Greek immigrants to the city. They are among the few works that provide a detailed account of Greek settlers in a major American city, let alone in the deep South. For readers interested in the development of the Greek food business, the book on the Bright Star tells the absorbing story of the 100+ year restaurant in Bessemer, a town close to Birmingham. The book pulls together appreciative statements by Bright Star customers on their experience at the venerable institution.

I am grateful for the assistance of Sam Bonduris, the nephew of Tom Bonduris, the restaurant’s founder. Sam took time out to fill in crucial gaps in Bright star’s saga.

The oral history interviews conducted by the Southern Foodways Alliance with key figures in the Greek food business were of enormous help.

The New Patrida, the Story of Birmingham’s Greeks, contains compelling portraits of pioneering ethnic entrepreneurs in the city.

Sofia Petrou’s A History of the Greeks in Birmingham is a ground-breaking study.

Birmingham Food: A Magic City Menu by Emily Brown skillfully covers the city’s culinary landscape.

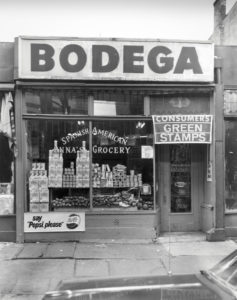

Meet Me at the Bodega

“Yes, AOC, DC Does Have a Bodega Culture…,” the Washington Post proclaimed. The New York City representative had been lamenting the absence of these New York City corner shops in her new home. Increasing references to bodegas in Washington were getting tiresome. Wasn’t this neighborhood gathering place a quintessentially New York City institution? Why did DC even have to lay claim to it? Was the Capital City developing an inferiority complex?

A New York City Bodega

Bodega had filtered into the popular lexicon. People were using it casually as a catchall term for quick food convenience stores, whatever their lineage. What sense did it make, for example, to dub a Korean grocery store a bodega? Using the expression conveyed a certain worldly acquaintance with what had once been a marginal outlet—at least marginal to these onlookers.

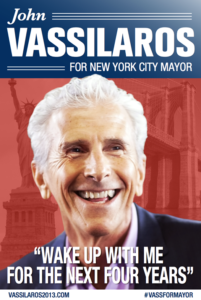

New York politicians now must pay homage to the bodega, just as previous campaigners had paid mandatory visits to a knish bakery. God forbid that a vote seeker would mistake another type of store for the real thing. During the recent New York City Mayor’s race, Andrew Yang committed this blunder. He saluted a grocery, more like a sanitized Whole Foods, where he bought a banana and a bottled tea as a “bodega.” He was roundly chastised for his error.

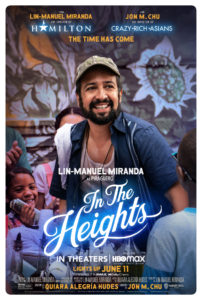

Lin-Manuel Miranda, Creator of “In the Heights.”

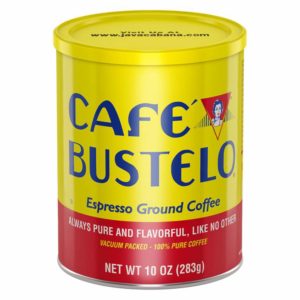

The bodega was coming out of the shadows. The HBO adaptation of “In the Heights,” a Broadway musical created by Lin-Manuel Miranda, celebrated this neighborhood fixture. Set in Washington Heights, a predominantly Dominican section in New York City, the show revolved around a Latin store and its young Dominican owner, torn between his ties to his community and his longing to return home. The mock bodega featured props like the red and yellow cans of Café Bustelo, the strong Cuban coffee, which had become popular in hip circles.

The Popular Cuban Coffee, Cafe Bustelo, Often Sold in Bodegas.

The bodegas I knew were shops, owned largely by Dominicans. First established in Latin immigrant neighborhoods, they now dotted many corners of the New York metropolitan area. They still serve Hispanic regulars, cash their checks, give credit and share news and gossip. As young urbanites moved into the city, they discovered the bodega. It is a handy place to buy egg and cheese rolls, coffee, and other daily necessities.

Map of Puerto Rico.

Immigrants from Puerto Rico pioneered the bodegas in New York City. The proprietors were part of a large wave of islanders who descended on the city after World War II. They built a colony in East Harlem, the barrio, as it was known, a neighborhood that had previously been settled by Irish, Germans, and Italians. Corner stores or bodegas, a name borrowed from the Spanish word for tavern or wine cellar, were haunts for immigrants first in East Harlem and later in the Bronx or Brooklyn. Owners sometimes set up a table outside for the locals to play dominos. The owner, or bodegerio, cared for customers’ everyday needs. “People come to a bodega when they want something small or quickthat’s our secret,” Albert Sabater, an owner told The New York Times’ Mariane Howe.

Prudencio Unanue with His Wife.

The owners needed business advice: what goods to stock and where to get them cheaply. A young go-getter, Prudencio Unanue, stepped in to help the budding enterprises. A native of Spain, who had migrated to Puerto Rico, he moved to New York City in 1918. Ten years later, he opened a small import business to bring food products from his homeland. His target was Spain’s large émigré community centered in the Manhattan neighborhood of Chelsea. The influx of Puerto Ricans convinced him that there was a larger market to tap. Unanue called his venture Goya.

The new arrivals were a different breed from the Iberians. They were “one of the first groups to migrate in masses,” Gerard Colon, Goya’s marketing director, recounted. The company built a food packing plant in Puerto Rico. The island pipeline provided the immigrants with products that “reminded them of home,” Unanue’s son, Joseph, recalled.

Goya Beans and Grains.

Goya cultivated the bodegas. “In the ’50s, we sold only to bodegas. The bodegas created us,” Joseph Unanue said. Goya’s wide array of goods filled the stores’ shelves: rice and beans, boxes of dried salt cod, amber bottles of guava, coconut, and tamarind syrups to make tropical drinks, papaya and guava preserves, and glass jars of black pepper, cumin, sesame seeds, and other spices.

The bodega would change hands. A new immigrant group, the Dominicans, was streaming into “Nuevo Yorko,” as they called it. The more than 500,000 Caribbeans became one of the city’s fastest growing groups. As the Puerto Ricans left their businesses, Dominicans, from the early sixties to the eighties, filled the void. “They started retiring and their kids were going into the professional world,” Luis Salcedo, the Dominican-born director of the National Supermarket Association, said. The Dominicans modeled their businesses after their homeland’s convivial markets, or colmadas.

Map showing the Dominican Republic.

Government workers, cab drivers, cooks, and factory hands from the island provided a strong customer base for the Dominican bodega’s wares. Goya’s salesmen again provided wise counsel. “They are very loyal customers to our products,” Goya executive Conrad Colon pointed out.

Both the Puerto Ricans and the Dominicans shared common tastes. “The basic thing is the olive oil, garlic, and oregano,” Colon noted. Each group also had particular preferences, and Goya tailored its product line accordingly. Puerto Ricans favored pink (rosada) and kidney (marca diabla) beans, while the Dominicans were enamored of the red roman or cranberry bean.

The bodegas spread out to Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania. The entrepreneurs, for example, found an opening for their businesses in Waterbury, an old industrial town in Connecticut’s Brass Valley, where the Irish, Italians, and other early immigrants had settled.

Map of Yemen.

The bodega business in now in flux. Even though Dominicans still hold a commanding position in the market, new ethnics have been attracted by the business opportunities. Yemeni immigrants are now the most visible of the new recruits in New York City. In Brooklyn, where they have taken the helm of many corner shops, the change is striking. “Lamb over rice is on offer at my local Yemeni owned bodega,” writer Quizayra Gonzalez observes.

Yemenis have a long immigrant history in America. They initially labored in auto plants in Detroit and steel mills in Buffalo. Weary of toiling in declining industries, they turned to small business. “By culture, we are traders,” Abdul Nashir, principal of an Islamic school in Lackawanna, a town next to Buffalo, remarked. On Buffalo’s east side, the Buffalo News reports, Yemeni shops have sprung up “to sell everything from frozen meats and bread to scented body oils and winter jackets and gloves.” The immigrants have followed a similar route in other cities. Yemenis control Oakland, California’s liquor business and operate many convenience stores in the Detroit area.

Yemenis, some of whom fled Buffalo’s steel mills, have joined a community of Arab merchants in downtown Brooklyn. “Every kid back in our town in Yemen knows the names ‘Court Street’ and ‘Atlantic Avenue,’” Ibrahim Qatabi, a Yemeni activist, told Christina Goldbaum of The New York Times. Owners often hired relatives who, after learning the ropes, were eager to start their own shops.

Nasim Almuntaser at His Family’s Bodega in Brighton Beach.

The tight kinship ties in the Arab state encouraged the patronage relationship. “Yemeni society as a whole is structured far more along clan society- and clan-based lines than any of the other Arab countries, Moustafa Bayoumi, a Brooklyn College professor, told Kiran Sury, a City Limits writer. Proprietors maintain their family connections in Yemen, sending back funds. “They also want to keep very much a foundation within Yemen because it’s a very remittance based economy,” Bayoumi added. “And so people tend to go back and forth a lot.”

The storekeepers, who prefer to call their shops delis or convenience stores rather than bodegas, carry products similar to those in Latin stores. The stores, however, may have a prayer room in the basement, and only sell halal meats, not pork.

A Bodega Mini-Mart in New York City.

The owners have banded together to form the Yemeni American Merchant Association. The organization caught The New York Times’ attention in 2019, when it protested President Trump’s travel ban by closing their shops and gathering for a rally in downtown Brooklyn. The President’s order hit home. It threatened to stop Yemeni wives and children from reuniting with their families.

The owners are picking up American merchandising techniques. Ahmed Alwan, a bodega merchant, made a Tik Tok video showing him playing a math game with a customer. As reporter Quizayra Gonzalez tells it, the owner offered a prize, any item in the store, for a correct answer. The patron guesses right and reaches out to grab the one indispensable item in any bodega. Alwan quips, “Not my cat.” Some second generation Yemenis are eager to remake their parents’ bodega. One owner’s sons, The Los Angeles Times reports, prodded him to expand his wares to include “fresh squeezed juices, fruit shakes and organic breads.” Their father was adamant. He was comfortable with the store as is.

“Why Are All the Pete’s Restaurants Named Pete’s?”

Pete’s Restaurant, Greenville, South Carolina

“Why are all the Pete’s restaurants named Pete’s?” the headline of a story in the January 9, 2000 Greenville News asked. The reporter, Mike Foley, observed that these eateries in the South Carolina textile town and the surrounding upcountry area were more likely to be run by owners with Greek names like Spiros and Georges. But “that doesn’t stop customers asking for Pete when they walk in the door, sit at a Formica-top table and get a whiff of hamburgers grilling and onion rings frying,” Foley writes. “Everybody says, ‘Where’s Pete? Where’s Pete?’ said George Mastorakis, owner of Pete’s Drive No. 7 in Greek,” the article continues. “But there’s no Pete.”

Pete’s Diner, Greenvile, South Carolina

The common names can cause confusion among customers, Foley notes. People forget where they had dinner or ordered takeout. “I’ll have people call here and complain,” one operator told him. “I’ll have people call here and complain. They’ll say they just came in here and got an order of jumbo shrimp here. They just pick the wrong number out of the book.”

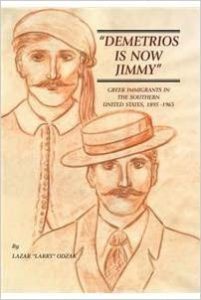

Lazar Odzalc’s book about the Americanization of Greek immigrants

Eager to fit in, Greek businessmen were afraid to call attention to themselves. Foreign names, even serving ethnic food, were roadblocks to Americanization. In Southern towns, the newcomers were easy targets for the xenophobic. In the early 20th Century, the Atlanta Constitution, scholar Marni Davis reports, frequently tarred Greek merchants as “dagoes.” A name change was a characteristic response. “Demetrios Is Now Jimmy,” historian Lazar “Larry” Odzalc titles his book on Greeks in the South.

Map of Greece with Peloponnese shown in red

Fleeing the rugged, unforgiving land of the Peloponnese peninsula at the turn of the twentieth century, Greeks journeyed to South Carolina. Although we associate Greek immigrants with big cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago, the South was also a popular destination. Mostly bachelors, the pioneers sought out Southern cities whose economies were expanding. The “New South” was advancing, growing into a commercial and industrial region bursting with employees needed to run the factories, insurance companies, and sales offices. Entrepreneurially minded Greeks spotted an opening for their talents. The workers were consumers and the immigrants saw themselves as providers for their wants. They built food businesses to cater to the working and middle classes. The innovators were breaking new ground in the South, creating a niche where none existed.

Food Offerings from Pete’s Clock Restaurant, Greenville, SC

The early ventures in South Carolina suited the Greek temperament. Averse to toiling as hired hands in mills and factories, the newcomers yearned to be their own bosses. Selling produce from pushcarts was a common starting point. Candy shops, a favorite business of Greek immigrants throughout America, were another stepping stone. These businesses often sold ice cream, sandwiches, and other quick fare. Three such stores, historian Judy Bainbridge points out, had opened by 1907 in downtown Greenville. From sweet shops, Greeks often embarked on the restaurant or, more specifically, the quick lunch business. By the middle of the 1920s, Bainbridge says, the budding ethnic merchant class dominated Greenville’s food business. By that time, 14 Greek lunchrooms were serving hot dogs, sandwiches, and similar items that did not offend Southern tastes.

Storefronts with comforting names like Tom’s Nickel-Up, Post Office Café, and Quick Lunch betrayed little of their owners’ origins. Their locations were shrewdly chosen. In Greenville and other South Carolina towns, the Greeks set up shop on the main commercial downtown streets.

Menu from Pete’s No. 4, Greenville, South Carolina

News of the alluring opportunities in South Carolina spread. Eager to replicate their success, kinfolk of the owners headed for South Carolina. “An immigration chain led family members and others from the same village to settle here,” historian Bainbridge writes. The new arrivals capitalized on these connections. Finding a job in a kinsman’s restaurant and learning the ropes was excellent preparation for opening one’s own business. Journalist Foley describes a Greenville eatery, owned by Spero Contis, where new immigrants apprenticed. “Pete’s Original served as a makeshift training school for restaurant owners. Most all the Greeks who work in the business have worked here,” Contis said. A constant stream of immigrants thus replenished the Greek food trade.

St. George’s Greek Orthodox Church, Greenville, South Carolina

The entrepreneurs gradually put down roots. The early colony of bachelors blossomed into a settlement of families. More and more Greeks left the city for homes in the suburbs. Craving acceptance, Bainbridge notes, owners joined the Masons, Odd Fellows, and other societies. The immigrants were assimilating but still clung tenaciously to their traditions. During the Thirties, families joined together to build the St. George’s Greek Orthodox Church. During World War II, congregants demonstrated a patriotic spirit. They bought war bonds and raised money to purchase a plane. The women of the church, Bainbridge recounts, put on a “spaghetti dinner Greek style” to raise money. St. George’s would organize regular festivals featuring Greek food, music, and dancing, which won friends among the locals. Nick Theodore, an insurance executive active in the church, personified the Greek ascent into the mainstream. “Uncle Nick,” whose parents emigrated from Sparta, was the first American of Greek ancestry elected to the South Carolina state legislature. Theodore went on to serve as the state’s lieutenant governor from 1987 to 1995.

The new generation of Greek restaurant owners is bolder than the lunchroom pioneers. More Greek food is on offer in the Greenville area, even if it is sometimes altered for the Southern palate. Tzatziki, souvlaki, spanakopita, pasticcio, and other Greek standards attract a curious and adventurous clientele. No longer reticent, the merchants broadcast their ethnicity with restaurant names like Ji-Roz, Kaires Mediterranean, and Greektown Grill. Old school owners would have been proud of their successors.

A Greek-American Odyssey:

New Hampshire’s Puritan Backroom Restaurant

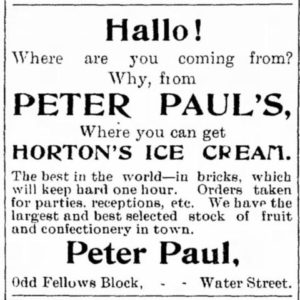

Arthur Pappas and his sister Pamela Goode in front of the Puritan. Photo by Kendal J. Bush

It’s a ritual. Candidates for the presidential primary in New Hampshire head for the Puritan Backroom restaurant in Manchester to shake hands and greet customers who crowd the establishment. The Puritan is an unlikely name for a business two Greek immigrants started more than 100 years ago as an ice cream and candy shop. Through several incarnations, it blossomed into today’s spacious dining rooms. U.S. Congressman Chris Pappas, whose father, Arthur, runs the Puritan, is the fourth generation family member to be a partner in the Manchester landmark.