“Sometimes You Feel Like a Nut”: An Immigrant and His Candy Bar

Peter Halajian

It is an improbable story. In 1890, a newcomer to America, an Armenian born in Turkey, takes a job in a rubber plant in Naugatuck, Connecticut and moves on to try his luck in the candy business. The young man, Peter Halajian, was seeking refuge from the oppression and economic hardship his people suffered under the Ottoman Empire. Halajian would become the founder of the Peter Paul Manufacturing Company, the maker of the Mounds Bar. Its 1980s jingle, “Sometimes you feel like a nut, sometimes you don’t,” advertised its marquee products, Mounds and Almond Joy.

Halajian was following a path pursued by many Armenians who journeyed to the U.S. in pursuit of jobs in the country’s surging manufacturing economy. Companies hired the immigrants in the industrial heyday of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to fill low-rung, cheap labor jobs. Woolen mills; wire, iron, and steel plants; and packing houses put the recruits to work. Immigrants sometimes knew little of their destination other than the name of the plant whose reputation had lured them. Armenians arrived in Lynn, Massachusetts, historian Robert Mitak points out, in search of the White Shoe Company, rather than the industrial town outside Boston. Unwilling to accept these positions as their permanent lot, Armenians were known for their eagerness to break the bonds of factory life. Entrepreneurial independence was a goal that Halajian shared with many of his compatriots. “As soon as I could I started a business on my own for I do not like to work for other people” one Armenian told the U.S. Immigration Commission.

Early Mounds candy bar wrapper

Naugatuck, where Peter Halajian settled, was located in a region that was a seedbed of early American manufacturing. Drawn by the Naugatuck River Valley’s abundant and cheap water power, employers built thriving mills in Ansonia, Waterbury, Seymour, and Shelton, names familiar to anyone who has heard a conductor recite them on a Metro North train. These firms made brass, chemicals, rubber, and other basic industrial goods.

The economy of Naugatuck revolved around rubber, an early enterprise in the western Connecticut town not far from New Haven. It was here in the 1840s that the industrialist Charles Goodyear developed the pioneering methods of vulcanization. The U.S. Rubber Company, founded in 1892, as a giant combination of small businesses, was a magnet for immigrants. Many laborers lodged in tenements and rooming houses on Rubber Avenue and its nearby streets. The city, from which naugahyde got its name, was also known for Keds, the shoes assembled by workers at U.S. Rubber.

Rubber was so dominant in Naugatuck that other, less visible businesses were overshadowed. Gregg Pugliese, a native of what he calls this “factory town,” was fascinated by its rubber industry when he decided on a graduate school research project. In the course of his investigation, the then-social studies teacher at the local high school stumbled on an enthralling part of Naugatuck’s lore, the history of Peter Halajian and the Mounds bar. Previously unknown to the young man of Italian ancestry, this story brought him a wider and more enthusiastic audience than a chronicle of the rubber industry ever would have. Pugliese recounted the saga in lectures and articles.

As Pugliese tells it, Halajian’s stint in the rubber plant was a relatively brief one. He quickly tired of the regimented factory routine. As soon as he met his quota of piecework, typically by early afternoon, Halajian would begin peddling baskets of fruit and homemade candy with his daughters, Mary and Lillian. They sold their wares to people who filled the Naugatuck train station and other stops along the busy rail line that ran the length of the Naugatuck Valley. Halajian also went from house to house hawking his products and soon opened a fruit stand.

Ad for Peter Paul’s candy store

In 1895, he established his own candy store in Naugatuck vending peanut brittle, licorice, lemon drops, caramels, and other sweets, as well as fruits and ice cream. He wooed customers with handbills promoting his products, according to the Famous Brand Names blog:

Peter Paul has very good food

You don’t throw any down the chute

His delicious ice cream your dreams will haunt

The more you eat it, the more you want

Ice cream soda the year round

No better soda was ever found

His homemade candy will make you fat

To Peter Paul, take off your hat.

As sales increased, Halajian added another store in Naugatuck and opened one in nearby Torrington.

The entrepreneur dropped Halajian, his last name, and legally changed it to its English equivalent, Paul. The signs on his shops carried the name “Peter Paul.” The pressure of selling to an American market would similarly force the Colombosians, another Armenian business family, to change the name of their yogurt to Colombo. “Nobody could pronounce our name,” son John Colombosian told me.

Peter Paul’s Cream Mints

From retailing, Peter Paul jumped into manufacturing. Teaming up with five Armenian friends—Calvin K. Kazanjian, George Shamlian, Jacob Hagopian, Harry Kazanjian, and Jacob Choulijian—he launched the Peter Paul Manufacturing Company in New Haven in 1919. The group pooled together $6,000, each putting up $1,000. In their 50’ by 60’ loft, husbands and their wives made their own candies at night. Since they had no refrigeration, this was a necessity. The system had its rewards: Products were ready to be sold fresh in the morning. Peter Paul turned out a line of lollipops, candy kisses, peanut brittle, and other popular items. The company’s first breakthrough was the Konabar, a mixture of nuts, fruit, chocolate, and what would become the business’s trademark flavor, coconut. In 1921, one of the partners, George Shamlian, concocted a recipe for a dark, bittersweet chocolate candy with a creamy coconut filling. The Mounds bar was born, and a marketing slogan—”What a bar of candy for five cents!”—was coined.

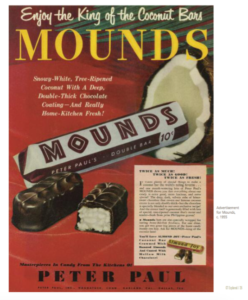

Ad for Mounds bars

Assembling the new product was laborious. The candy had to be shaped, rolled, dipped by hand in chocolate, and then wrapped in foil. Before long, the business was burgeoning and the company was outgrowing its space. The factory also desperately needed machinery to more efficiently meet their rising demand. The solution was to build a new facility. With a $35,000 loan from the Naugatuck National Bank, the partners left New Haven and, in 1922, built a plant in Naugatuck, where Peter Paul had learned the candy trade. With new equipment, they transformed what had been a handicraft operation into a larger-scale factory. During the 1930s, machines to coat chocolate, wrap the candy, and to refrigerate their products were installed. Unlike some other firms, Peter Paul was able to withstand the Depression and even to prosper. New items like Thin Mints, After Dinner Mints, and Bachelor Bars (filled with sesame seeds) supplemented their top-selling Mounds bar.

Peter Paul factory in Naugatuck

Peter Paul, who had been ailing, died in 1927 and his associate, Cal Kazanjian, took the helm. The new chief, as writer Liana Aghajanian pointed out, won over customers with a personal touch: “Mr. Kazanjian used to carry a little box of ‘Mounds’ around with him,” wrote reporter Wesley S. Griswold in The Hartford Courant. “When he entered the broker’s office, he would take one of the coconut bars out of his pocket, remove its tinfoil cloak, deftly break the chocolate-covered confection and offer the broker a taste.”

During World War II, the company’s fortunes continued rising. Shortages of sugar and other ingredients pushed Peter Paul to concentrate its efforts on producing Mounds bars. The military became the company’s largest customer, ultimately buying 80% of its products. The firm shipped out 100,000 pounds of candy a day. Considered a high-energy item, the Mounds bar was now an essential part of the soldiers’ rations. “There’s a lot of religion in a candy bar,” one military chaplain said, according to Patch.com poster Terri Takacs.

The business developed into the world’s largest consumer of coconuts. So vital was this raw material that Peter Paul had to create an ingenious supply route when its Philippines source was cut off by the Japanese invasion. The company sent a contingent of small schooners to islands in the Caribbean to buy coconut. The “Flea Fleet,” as it was called, was not bothered by the Germans. But the boats were able to gather valuable intelligence about the routes the Nazi ships were taking. As an extra bonus, Greg Pugliese reports, Mounds provided the military with empty coconut shells to make gas masks.

Newspaper headline: Nazi found with Mounds bar

Peter Paul’s service to the military stayed a secret until a search of a Nazi prisoner of war extradited to New York uncovered a Mounds bar in his belongings. “German General Is Found to Be in Possession of Peter Paul Mounds,” read the headline in the July 20, 1945 issue of the Naugatuck Daily News. “Sticking out like a sore thumb among the array,” the paper wrote, was the chocolate candy. Speculation was that the Mounds bar had been stolen from an American PX in Europe.

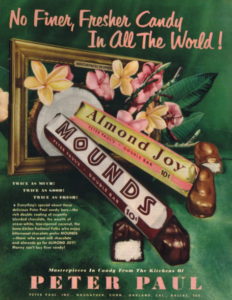

Ad for Mounds and Almond Joy candy bars

By the end of the hostilities, the fame of the company’s product had spread. The Mounds bar already had a loyal customer base among G.I.s and their families. A companion candy, Almond Joy, was introduced in 1946. The firm took clever advantage of new media, first radio and then television, to advertise its products. Mounds was the first candy company to buy time on network color television in the 1950s. The singing Peter Paul Pixies were featured in ads extolling the Mounds bar as “indescribably delicious.” The company also hired broadcasting personality Arthur Godfrey as spokesman for their brand.

Armenians took great pride in Peter Paul. Some even bought stock in the company, lawyer Harry Mazadoorian observes. Holiday dividends were paid in free candy bars. The candy’s flavor, one Armenian observed in an email response to an online article, was transporting: “When we first immigrated to America, Mounds bar was our family’s favorite,” Silva Elmedejian wrote. “It was closest candy to middle eastern taste. Now I know why. Proud of our . . . Armenian ancestors. I will keep on eating them until I die.”

Like many small firms, low on capital, it was hard for Mounds to resist the overtures of bigger companies when they came courting. Cadbury Schweppes bought the enterprise in 1978, and Hershey’s acquired it ten years later. In 2007, Hershey’s shut down the Naugatuck plant, which had been manufacturing Mounds for 85 years. Jack Tatigian, a long-time company executive, mourned the demise of the factory: “In Naugatuck, you worked for the rubber company, the glass company, or the candy company,” he told The Naugatuck Republican-American. The facility that had long made a product, the brainchild of Armenian immigrants, was discarded, swept aside as if it were a used candy wrapper.