Blood on the Vine: The Passion Fruit

The fresh acidity of the juice was a regular pleasure of my year-long stay in Dar es Salaam, the Indian Ocean port in the East African nation of Tanzania. On my weekly excursions to Haleeds, an Arabic-Persian hole in the wall restaurant near Dar’s Indian quarter, I enjoyed a glass of passion fruit juice with my standard order of moushkaki, spicy chunks of beef barbecued on a grill outside the eatery. The meat came with chapati, the Indian round bread.

I imagined this as my first passion fruit experience. The fruit, I found later, was actually an ingredient in Hawaiian Punch, a favorite drink of my childhood. The large blue can of tropical potion passed for exotica during the barren 1950s.

Passion Fruit Mousse

As the years passed, I began stumbling on passion fruit in my explorations as an ethnic food writer. Cans of the carbonated juice lined coolers in the food shops of the Ironbound, Newark, New Jersey’s Portuguese enclave. On my visits there, the Brazilian Bakery on Ferry Street, the main spine of the neighborhood, was one of my first destinations. (A large influx of Brazilians has settled in the neighborhood in recent years.) On my train trip to New Jersey from Washington, I fantasized about the passion fruit milk shake, a specialty of the bakery. The passion fruit mousse in its display case tantalized me.

Play Ball, a Portuguese-owned lunch counter a few blocks up from the bakery, offered its customers an array of tropical fruit drinks ranging from papaya to tamarind. Passion fruit was one of the refreshments that the restaurant made from its storehouse of frozen concentrates.

In Montreal, which has a large Portuguese community, passion fruit was a staple of the drink offerings at my wife, Peggy’s, and my favorite barbecue house, Mile End Churrascaria Portugal. Swigging a glass of the fruit drink was a perfect accompaniment to the delightfully charred and spicy peri peri chicken brought from the grill to our table.

Back home in Washington, hip eateries were uncovering the delights of tropical produce. At Rocky’s, the late Columbia Road restaurant, chef Paul Petit was turning out jerked shrimp, Caribbean chicken curry, and guava-laced barbecue and creating inventive passion fruit treats. Owner Rocky Scott was attracted to the fruit because of its “tropical” associations. She served up passion fruit iced tea and hurricanes, a blend of its puree and orange, pineapple, and lime juice with doses of rum and triple sec. It infused Rocky’s chutneys and added a tingle to the menu’s creamy cheese cake.

Near Rocky’s, the Brazilian Grill from Ipanema dining room featured a batida, a strong drink made with passion fruit. The cocktail married maracujá (the fruit’s Brazilian name) with vodka and cachaça, a sugar cane brandy. A little sugar and condensed milk were added to the cocktail. The drink packed a wallop.

Passion fruit was now in vogue. Bartenders whipped up new drinks with the novel item and smoothies made with the juice were fashionable. I watched aspiring pastry chefs on the Great British Baking Show, the public television program, enhance their productions with its flavor.

Despite my infatuation with the fruit, I knew little of its background. I set out to uncover its mysteries by reading the works of botanists, chefs, anthropologists, and food historians.

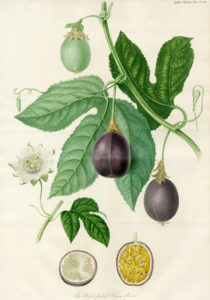

Seeds fill a cut-open passion fruit

The fruit, which I had assumed from my Tanzanian experience was African, actually originated in the Americas. Purple and yellow varieties of the egg-shaped fruit, were the most widely marketed types. Granadilla (“little pomegranate”), the Spanish name used in parts of Latin America, was an allusion to the many brown and black seeds that fill its orange-yellow pulp.

The plant is a climbing vine known as much for its brilliant blooms of white, orange, red, and purple flowers as for its luscious fruit. (Its scientific name is Passiflora.) The ideal setting for the plant is the wildness of the tropical rainforest. Nourished by heat and humidity, it can climb 15 to 20 feet a year. Clinging with its tendrils, the plant pushes its way to the canopy of the forest.

The route to understanding passion fruit led inevitably to Brazil. The vine was native to that country and the surrounding region. From the tribal peoples, the Portuguese settlers learned about the plant’s special qualities. The colonists began referring to the fruit with its Indian name, maracujá. As the plant spread, the name stuck, even in Spanish speaking countries like El Salvador and Peru.

Passion fruit later traveled to the mother country. Sweetened with sugar, which began pouring into Portugal from Brazil’s plantations in the mid-sixteenth century, it would become an important element in the country’s repertoire of sweets. Bakeries marketed passion fruit tarts, puddings, and mousses. Sweet, tart passion fruit juice also gained popularity. Undoubtedly, the Portuguese transported maracujá as they did pineapples, cashews, and other crops, within their empire. It may have reached Mozambique, historian Timothy D. Walker speculates, in Portuguese ships stopping over on their voyage around the Cape. At this East African way station, the fruit might have been helpful in protecting sailors and passengers against scurvy. From there, its journey to Tanzania possibly began.

Initially, it was not as a tangy fruit but as a healing agent that maracujá endeared itself to the Portuguese. The plant, the Indians taught them, worked wonderfully to remedy fevers. European physicians were soon persuaded of its medicinal benefits. From the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, the Materia Medica of Cambridge University, scholar Geri Augusto points out, listed it as a curative.

Passion Fruit growing on vines

In Brazil, it was the Jesuits who, in their missionary work with the native peoples, acquired the early knowledge of medicinal botany. Arriving in the mid-sixteenth century, friars pioneered in collecting information about the properties and uses of tropical plants. Other fruits prized by the Indians joined the maracujá in Portuguese medical lore. The juice of pineapple was praised for its ability to dissolve kidney stones. The fruit of the cashew tree, it was believed, alleviated fevers and stomach ills. (The cashew apple is the red and yellow fruit to which the familiar nuts are attached.)

The Jesuits, historian Walker found, established a network for treating patients with the drugs and for spreading the word about their discoveries. Members of the religious order were permitted to operate as druggists (boticanias), dispensing treatments to the sick. Apothecaries and infirmaries run by the friars were set up in Brazil and other parts of the Portuguese realm. The Jesuits even controlled two of Portugal’s major pharmacies. Their shops were well stocked with plant-based remedies like maracujá. The Jesuits, Walker adds, also passed on their learning to Portuguese administrators, naval commanders, merchants, and other officials. Medicinal extracts were sent to Goa, Macao, and other colonial outposts.

The Fathers also profited from their ventures. “Missionary orders relied on revenue from this trade to support their proselytizing work,” Williams points out. “The market for colonial medicines in Portugal was largely their exclusive domain for over 200 years.”

The Jesuits and other missionaries were convinced that passion fruit was not only a curative for the body but a godsend for the soul. They began calling the plant “passion flower” to evoke the Passion of Christ, his trials and suffering before his death.

Passion Flower

Missionaries in Latin America transformed the flowers into religious symbols. In the eyes of the proselytizing Christians, each segment of the flower became an emblem of the crucifixion. Jacomo Bosio, a 17th century monastic scholar working on a treatise in Rome on the Cross of Calvary, popularized the image of a sacred flower. Bosio seized on the drawings and descriptions of a singular flower sent by priests from “New Spain.” He wrote that the flower represented Christ’s torture. The floral crown with its blood red fringe symbolized the crown of thorns, “the Scourge with which our blessed Lord was tormented.” Its 72 filaments represented the exact number of thorns on Christ’s head. The three stigmas stood for the three nails on the cross and the stamens for the five wounds Jesus suffered.

Missionaries used the flower in their campaigns to convert the Indians. It was a tool, writer Clara Ines Olaja argues, to teach “the infidel Indian the truculent history of the passion of Christ.”

Excited by its symbolism, a party of Jesuits in 1605 honored Pope Paul V with a gift of the plant. They gave the pontiff a sketch of the passion fruit along with dried samples of it. He was enamored of the offering and its fame spread in Italy. “Members of the intelligentsia and ecclesiastic leaders were eager to acquire knowledge of the extraordinary flower,” the website of the History of Medicine and Ecclesiastic History notes.

To the clergy, the maracujá was providential. For one Portuguese-born priest, Franciscan Father Antonio de Rosario, the plant represented the plenitude of the New World. Writing in the early eighteenth century, according to scholar Federico Palomo, Rosario viewed it as a blessed offering from God. It was “the flower which the land produced for the glory of the Creator.” In the Eden of the Americas, the plant was an auspicious sign to the settlers. It also had more somber overtones. For Rosario, God had designed the “mysterious flower” to reveal “the deplorable tragedy of the Passion.”

Passion Fruit growing on a vine

The passion fruit exerted a powerful hold on the imagination of European writers and artists. In the Natural History of Brazil, authored by the Dutch physician William Piso and the German naturalist Georg Marcgraf and published in 1648, the maracujá is extolled. The first book to introduce the varied plants of the country, Brazilian specialist Amy Buono explains, highlights the dazzling qualities of the flower and fruit: “[T]he coloration of the interior of the flowers produces an iridescence in a broad range of cerulean purples, blooming fully three hours after dawn. The fruits, though, are produced primarily in the rainy, summer months.” The writers, Buono continues, were struck by “the black seeds contained within the fruit, and the delicious acidity of the black seeds inside.”

Passion fruit could do wonders for one’s health, she adds: “The fruit pulp can be used against fevers and can serve as a substitute for ‘cordial syrup,’ having various remedies, including numbing the teeth, restoring the body from heat exhaustion and thirst, awakening the appetite and guarding against stomach pains.”

The Natural History was also careful to emphasize the spiritual qualities of the plant. Even the tendrils, which enabled the passion fruit to climb, had a spiritual purpose. They stood for the whips used to maim Christ.

Mameluca, an oil painting by Dutch painter Albert Eckhout

Painters, scholar Buono observes, were also drawn to the passion fruit. In Mameluca, an oil painting by the Dutchman Albert Eckhout in 1611, its flower plays a central role. The mameluca, a woman of mixed blood stands beneath a caju [cashew] tree. With one hand, she held a basket of flowers among which was a prominent large white passion flower. With her other hand, the mameluca lifts her white gown.

Now a salable commodity, the passion fruit lacks the aura it once had. Sumol, the Portuguese beverage giant, is constantly seeking new outlets for its line of passion fruit and other soda drinks. As sales of its products have declined in Portugal, the company has looked to former colonies in Africa, like Angola, to pick up the slack. Cans and bottles of maracujá in stores from Newark to Luanda are a reminder of the nation’s once vast empire and its large diaspora.