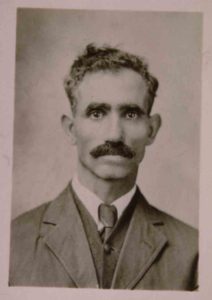

A young man from a small village in Greece’s rugged Peloponnesian peninsula set out on a journey in 1902. The 14-year-old Tom Bonduris was on a trek to improve his fortunes. Opportunities were few in Peleta, a mountainous community that sat on a plateau 2300 feet above sea level. “A farming village of traditional stone houses,” writer Niki Sepsas pictures it, it was “dotted with stately fir and cedar trees…. The pastoral setting was peaceful and idyllic.” For all its beauty, Peleta was a place where farmers labored to eke out a living from the soil. Farmers milled grain with the help of their horses and donkeys. Many owned goats and sheep. Wild greens were dried and saved to be consumed during the winter.

When Sam Bonduris, Tom’s nephew, visited Peleta many years later, he was struck by the harshness of the place. This village, once part of the Ottoman Empire, was “impoverished.” In 1971, Sam said, Peleta was still without electricity.

Peleta was blessed with a tight-knit family network. It was almost “tribal,” Sam observed. Tom Bonduris relied on these kinship ties during his journey. In New York City, Tom’s destination, the helping hand of a family member eased his arrival.

Tom got off the boat at Ellis Island and soon joined an uncle, Peter T. Bonduris, who ran a fruit stand in Manhattan. Peter had left Peleta in 1895 and took up a business that was a foothold for many early Greek immigrants. Peter put Tom to work. Part of the job’s appeal was that it required little English. John N. Bonduris, Tom’s first cousin, whom Peter took under his wing a few years later, discovered that hawking fruit demanded just a few words. He was taught to give the same answer to every customer’s question. His stock response, Sam says, was “I don’t know and 10 cents a bunch.”

After two years of learning the ropes at the fruit stand, Tom went home to Greece after catching pneumonia. Returning to America in 1906, he disembarked in Savannah, Georgia. He left there for Birmingham, Alabama for reasons that are somewhat murky. But, as Sam Bonduris guesses, his uncle had probably heard through the family grapevine that Birmingham was “booming” and that some Greeks, possibly relatives, had already settled there. That was enough enticement.

Tom’s journey took an intriguing twist. He began baking pies at a Greek-owned restaurant in Birmingham. A year later, Tom would found the Bright Star Café, now a 100-year-old establishment and the longest continuous restaurant in Alabama. The Bright Star is a monument, a testament to the achievement of Greek immigrants in building a flourishing food industry in the Birmingham area. (More about Tom later.)

Birmingham might seem an unlikely place for Greek immigrants to settle. Bonduris had actually arrived in a city where a Greek colony was already springing up. The deep South town was a community, no longer slumbering, but one energized by a budding industrialism that was attracting newcomers. In 1900, historian of Birmingham’s Greek immigrants Niki Sepsas notes, there were already 100 Hellenic pioneers. In ten years, the number would rise to 500.

In his book, Hellenic Heartbeat in the Deep South, Sepsas points to George Cassimus, a Greek seaman, as the first arrival. Cassimus had been working for the British navy running guns for the Confederacy out of the Alabama port of Mobile. After the war, George began looking for new pursuits. He moved to Birmingham in 1884, where he “found a brash young boomtown barely thirteen years old that was developing around what had just been a mud-spattered railroad crossing,” Sepsas writes.

Birmingham, named for England’s industrial powerhouse, was in the midst of a radical transformation, Sepsas says. “By the early 1870s … glowing blast furnaces had begun lighting the night sky, and coal and iron mines were offering employment to hundreds of former plantation workers and immigrants from other states and many foreign countries.”

Cassimus took a job with the city’s fire department. He put aside enough money to start a short-order eatery. Details about the business are thin, although the enterprise was known as a “fish eating place.”

Greek immigration to Birmingham was part of a larger stream of voyagers uprooted by economic hard times and propelled by the limited opportunities of their villages. Many were single men from farming families, often from the Peloponnesus. Initially, they envisioned their journey as a short-term sojourn, only long enough to accumulate a nest egg to bring home.

Some were motivated to earn money to fulfill family obligations. One such immigrant was Triantaffillos Balabanos, who left his village of Tsitalia in the early 1900s. He booked passage on the steamship Athinai, which was bound for New York from the Greek port of Piraeus. After a 13-day trip, he disembarked on September 29, 1909. He was not greeted with a welcome mat. According to writer Philip Ratliff, officials required him to swear that he could read, did not practice polygamy, and was not an anarchist. He listed his destination as the Reliance Hotel in Birmingham, one of whose owners was a kinsman, T. N. Balabanos.

Triantaffillos was on a mission. He wanted to work long enough to pay for a dowry for each of his five daughters. He returned home five times with the funds to meet his goal. He made money in restaurant jobs and at his relative’s hotel.

Triantaffillos, who went home in 1939 and never returned, left a legacy. George Sarris, a Birmingham food titan who founded the Fish Market food business, was his great grandson. Generations of Greeks in the restaurant industry carried the Sarris name.

“You weren’t here to change

the culture of America. You

were here to make a living.”

Every immigrant group in Birmingham followed a different path. The Italians captured the grocery business while the Jews, writer Sepsas observes, gravitated to “mercantile” occupations, like dry goods. In the early days, the Greeks ran a host of enterprises, lunchrooms, soda fountains, candy shops, meat markets.

Greeks shared a disdain for the factory jobs that abounded in the “Pittsburgh of the South.” Although some signed on as hired hands in factories, they were reluctant recruits. “You’re not going to work in steel mills or mines” over the long term, Sepsas, who himself had worked in several Greek hot dog businesses, observes. The Greeks dreamed of economic independence, of self-employment.

Industrial labor was not only grueling but dangerous. Constantinos Nicholas Sfakianos suffered through a perilous job. In 1907, the immigrant joined ten other countrymen at a steel plant in Ensley, a community in greater Birmingham. In an interview with a Birmingham research group, he recounted his ordeal:

“I stayed on that job fifty-three years, painting smoke stacks. There were no lights to work by so we burned wood for light for ten or fifteen years.

“I lost my hand in that plant in 1941. A crane in the blast furnace crossed my hand. Cut part of it right off. After six months, I went back to work. The company, the big boss liked me. He knew me because I worked there all my life.” (Source hereafter referred to as Patrida.)

Fruit vending was an early launching pad for the settlers. It was a good fit. Little English was required. Moreover, Sepsas points out, the immigrants had worked on farms back home and possessed a “pretty good knowledge of fruits and vegetables.” Sofia Petrou, a scholar who studied Birmingham’s Greek colony, suggests another inducement:

“The majority of the early Greek immigrants in Birmingham found a lucrative business in sidewalk fruit stands …. This type of small business allowed the Greek immigrant to assert the economic independence that had eluded him in Greece. All he needed was a small capital investment, usually acquired from his former homeland, and knowledge of the product he was selling.”

The immigrants’ commercial instincts served them well. In 1902, the Birmingham newspaper, The Herald, reported that the Greeks had acquired a monopoly of the fruit business. Christine Grammas describes one such operation run by her father, Sam Derzis:

“My daddy’s stand didn’t have a front door. It had counters with fruit stacked up just as pretty as you could see and then in the back he had an ice box where he would slice the watermelons and sell them by the slice. On one side he had candy counters where he sold Hershey bars, peanut brittle, and coconut crisp—and there was a cigar counter.” (Patrida)

Vending fruit might lead to more profitable ventures. Alex Kontos, who arrived in Birmingham in 1889, started out selling fruit from his horse and wagon. Later, he teamed up with a Mobile, Alabama wholesaler to market bananas, which were being shipped to the port. He introduced the then-strange, exotic fruit to Birmingham. Transporting bananas in box cars to the city, the “Banana King” soon controlled the sales of the fruit. Kontos later parlayed his enterprise into a full produce wholesale business.

The fruit dealers’ success bred resentment in the city’s business establishment. The vendors posed a public health threat, some claimed. One vehement opponent of the ethnic trade compared the Greeks to “Chinamen.” “They do not build up a town but send their earnings to the old country.” His tirade continued: “Which should we encourage, our home merchants … or these foreigners? It is a case of choosing between John Smith and Harry Williams or Demosthenes, Thucydides and Aristotle.” (Patrida) The Greek merchants won the fight. In a vote of 13-4, the city council permitted the vendors to continue their sidewalk trade.

The restaurant business, as it did in small towns and cities across America, exerted a strong attraction for Birmingham’s Greeks. It was their niche of choice. The savvy entrepreneurs spotted a gap in the market and decided to move quickly to fill it. The growing urban population hungered for inexpensive, quick, and filling fare. “Those industrial workers, many of whom arrived without spouses or children, clamored to wolf down lunch break sandwiches from portable canteens, to dine in cafés, to drink and carouse in taverns,” Southern food historian John T. Edge explains. The bold immigrants ventured into a field where old-line merchants were hesitant to tread.

In the process, the Greeks built a moderately priced food industry, one which had not previously existed. The culinary transformation of Birmingham was stunning. In 1912, a traveling salesman, Sepsas notes, heaped praise on the immigrants’ contribution: “The Greek-owned restaurant relieved a well-nigh intolerable gastronomical situation.”

Over the years, the Greeks in Birmingham plunged into a wide variety of pursuits. The hot dog business was an early favorite. In 1919, Tom Kandilas opened what was reputed to be the first or one of the earliest hot dog stands. Tom, who had previously worked in the fruit and vegetable trade, promoted the “Birmingham dog.” Tom’s Coneys, his shop, sold a “hot beef” frank, similar to the one that Greek vendors hawked in many locales across the country. It was spicy and was topped with mustard, onions, and sauerkraut. The piece de resistance of the dog was the “special sauce,” whose secret ingredients Greek merchants guarded zealously. It was probably flavored with cinnamon, allspice, and other tangy Greek spices.

The stories of colorful ethnic vendors became part of Birmingham lore. Emily Brown, a local food writer, relates one such tale about Kandilas. As his granddaughter, Tasia, tells it, Tom kept a half pint of liquor next to his cash register. For special customers, he might pour a bit into their coke bottles.

The roster of hot dog peddlers in Birmingham included such names as Pasisis, Koutroulakis, Graphos, and Gerontakis. “Forty years ago, hot dog merchant Lee Pantazis told writer Bob Carlton, “you couldn’t throw a stone without hitting a Greek hot dog stand, whether it was a little restaurant like this or a cart on the side of the road.”

The business was well suited for early Greek immigrants. “You have to remember,” Birmingham restaurateur George C. Sarris told an interviewer, “when [the Greek immigrants] first came here, they had no language, no nothing. Hot dogs were easy. There was little cooking. A hot dog and a sauce, that’s pretty much it.”

Other innovators branched into a great variety of enterprises. During the decades, Greeks launched barbecue, “meat and three” (more about that later), and even white tablecloth dining rooms. Blanketing the city with their eateries, Greeks came to dominate Birmingham’s food business. “We laugh and say, if it hadn’t been for the Greeks in the ’60s and ’70s, the people of Birmingham would have starved,” Tim Hontzas, owner of Johnny’s restaurant, told correspondent Bryan Roof.

The restaurant owners had a keen feel for the tastes of their customers. In the beginning, they played down their heritage and instead offered familiar, inoffensive dishes. “You didn’t see Greek people serving spanakopita and tiropita and keftedes and this and that,” Hontzas explained to journalist Georgia Clarke. “They served barbecue and they served hot dogs and they served meat and three—Southern cuisine.”

On the road to success, the Greek restaurant journey could sometimes be a rocky one. Birmingham natives might cast a suspicious look or toss an epithet at the “aliens.” Some might sneer at the “dagoes,” an offensive term usually applied to Italians. “Greeks were sometimes asked to sit in the black sections of restaurant establishments and were discouraged from housing in certain parts of Birmingham,” historian Petrou points out.

Greeks often modified or changed their names to appear less conspicuous. Writer Sepsas tells the story of a Greek immigrant, Chris Mitchell, who felt impelled to do this: “My father, Nicholas Mitchinikos, came to America in 1898 and settled in Birmingham. He was twelve years old at the time. A man took him to find work. ‘No speak English,’ my father said. The employer asked him his name and he answered ‘Mitchinikos.’ ‘Too hard,’ the man replied. ‘Let’s make it Mitchell.’ That became the family name.”

The xenophobic climate strengthened the already powerful determination of these immigrants to earn acceptance and recognition. For restaurant owners, the food business became a pathway to belonging and moving up in a foreign land.

For Greeks with an entrepreneurial drive, there was also plenty of fertile soil to plough near Birmingham. After a year in Birmingham, the pioneering Greek immigrant Tom Bonduris was restless. Eager to work for himself, he struck out for Bessemer, a town 15 miles west of Birmingham. The boom town was the brainchild of Henry Fairchild DeBardeleben, a go-getter born on a cotton farm, who had tried his hand as a teamster boss, a lumberyard foreman, and in other occupations. With two partners, he began laying plans to create a city that would take advantage of the region’s rich veins of coal, iron ore, and limestone.

The visionary imagined a city built around eight blast furnaces and fed by eight railway lines. He laid out his boundless dream, Sepsis notes, to the Birmingham Age journal in 1886: “We are going to build a city solid from the bottom and establish it on a rock financial basis. No stockholder will be allowed in who can’t make smoke. It will take $100,000 to come in and the man who can make the most smoke can have the most stock.”

A year later DeBardeleben’s dreams were realized. Originally called Brooklyn, the city’s name was aptly changed to Bessemer, after the British inventor of the process of transforming molten iron into steel. The Bessemer technique, a boon to the city’s industry, made steel production more efficient and less costly. Before long, Bessemer would burgeon, rising to become the state’s fourth largest city by 1890. The city now throbbed with blast furnaces, iron works, and steel mills.

For a young man with his eye on the main chance like Tom Bonduris, Bessemer offered alluring possibilities. The teeming city was drawing miners, mill workers, and office employees, all potential customers for a lunchroom. Several trains roared through the city each day, bursting with miners, sometimes hanging on the side.

Tom opened the Bright Star Café in 1907. A neon sign, star-shaped, with the business’s name proclaimed the young man’s aspirations. Tom must have been thrilled about this venture. “He came to this country as a young thing. He worked as a waiter,” future Bright Star owner Jimmy Koikos told Amy Evans from the Southern Foodways Alliance (hereafter as SFA). “And he heard about Bessemer being the young, mining, progressive town, so he came here and … opened up the Bright Star.”

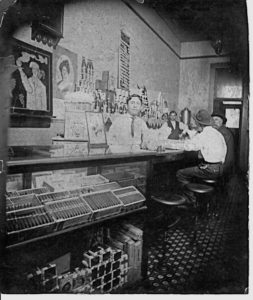

The Bright Star was conceived as a working people’s café. The setting was simple, functional. A horseshoe-shaped bar sat probably 35 patrons on its stools. There were no tables or booths. The counter contained a glass case full of cigar boxes.

During its infancy, the Bright Star fed its customers basic unadorned fare. “Blue collar workers,” historian Sepsas says, were its bread and butter. To serve workers as they came off their shifts, the eatery ran 24 hours a day. The atmosphere of the Bright Star mirrored that of the city. “The town of Bessemer was booming,” Jimmy Koikos said in an oral history. “It was just people coming from mining towns—coffee, donuts, chili.” “Maybe about … four-thirty or five [in the morning] they would clean up and getget ready. And then there’d come breakfast and people going.” (SFA)

As the business caught on, the menu evolved. Honoring Southern tradition, the Bright Star began offering a “meat and three” or a “plate lunch,” as it was originally called. For hard-to-beat prices, patrons could choose among chicken-fried steak, catfish, or other main dishes and select three from an array of fresh vegetables like okra, pole beans, and fried green tomatoes. Long before “farm to table” became a fashionable culinary trend, Greek merchants, many of whom came from rural families themselves, were purveyors of the country food that Southerners cherished.

Tommy Bonduris, another member of the restaurant clan, who worked as a bus boy at the Bright Star, described its fare: “A plate lunch at the restaurant in those days went for twenty-five cents. You got meat, three vegetables, a dessert and a drink. Coffee and doughnuts were a nickel.”

The “meat and three,” the eminent Southern food writer John T. Edge told journalist Adam Rhew, was “the foundational Southern meal.” This plate, the “bedrock of Southern culture,” had deeper roots than either fried chicken or barbecue. Country migrants to the city, Edge observes, brought their culinary affections with them. “As the Southern worker transitioned from farm to city, you see this meal arise…. It was food for people who plowed the back forty (side of the farm) …. Reinterpreted for people who work at desks and in factories, catching lunch breaks in the city instead of returning home for lunch.”

Serving this plate paid dividends. “Southern food was a way to assimilate,” Beba Touloupis, an owner of Ted’s Restaurant in Birmingham, told a trade publication. Pete Hontzas, who helped run Niki’s, another eatery in the city, offered a blunter explanation for this practice. “They did serve some Greek dishes, but you had to serve what people would buy,” he explained to writer Jennifer Kornegay. “You weren’t here to change the culture of America. You were here to make a living.”

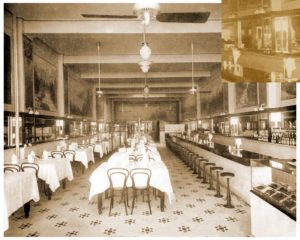

The Bright Star went through several incarnations, moving from location to location as the restaurant grew. Its fourth and final address in 1915 was in the heart of Bessemer’s thriving central business district. The choice of the site was deliberate. Hoping that the Bright Star would be imbued with the city’s vibrant energy, Tom Bonduris placed it in the center of commerce.

The Bright Star’s decor enhanced its appeal. Ceiling fans, hand-tiled floors, mirrored and marble walls, and marble countertops were highlights of the establishment. It had the feel, some observers felt, of a French café in New Orleans.

Hand-painted murals done by an itinerant German artist stood out. The story behind these paintings is part of Bright Star lore. As later owner of the restaurant Jimmy Koikos tells it, this footloose artist was “kind of just really like a wino, but he had talent.” Owner Tom Bonduris liked his work. “So he painted a European thing. And then he painted these murals one by one. Put them up. Then they fed him and wined him and he just wandered on through. He never dreamed they’d be up ninety years later.”

The interviewer probed further. “So did he just do it for trade?” “For trade and maybe we talk—talked to Mr. Bonduris a little bit—maybe a little money,” Jimmy said. (SFA)

Years later, seeing the “nicotine-patinaed murals” and eating a meal at the Bright Star was a moving experience for writer John Edge. He “realized that restaurant is its own kind of working man’s cathedral,” he told journalist Bob Carlton. “It’s an impressive place in which to sit, and yet is still mundane enough for people to have lunch there.”

(To Be Continued)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS & THANKS

I am indebted to Niki Sepsas, a Birmingham-based writer, for sharing his extensive knowledge of the area’s Greek community. Sepsas’s books, Hellenic Heartbeat in the Deep South and A Centennial Celebration of the Bright Star Restaurant, whose contents he assembled for the business, are invaluable guides to the history of Greek immigrants to the city. They are among the few works that provide a detailed account of Greek settlers in a major American city, let alone in the deep South. For readers interested in the development of the Greek food business, the book on the Bright Star tells the absorbing story of the 100+ year restaurant in Bessemer, a town close to Birmingham. The book pulls together appreciative statements by Bright Star customers on their experience at the venerable institution.

I am grateful for the assistance of Sam Bonduris, the nephew of Tom Bonduris, the restaurant’s founder. Sam took time out to fill in crucial gaps in Bright star’s saga.

The oral history interviews conducted by the Southern Foodways Alliance with key figures in the Greek food business were of enormous help.

The New Patrida, the Story of Birmingham’s Greeks, contains compelling portraits of pioneering ethnic entrepreneurs in the city.

Sofia Petrou’s A History of the Greeks in Birmingham is a ground-breaking study.

Birmingham Food: A Magic City Menu by Emily Brown skillfully covers the city’s culinary landscape.