It is thrilling to uncover nuggets buried in America’s ethnic history. Even before I started seriously writing about ethnic food, I was drawn to New Orleans. Its mix of cultures was fodder for my imagination. The port city I fixated on was an ensemble of African, Latin, French, and Creole flavors. In the beginning, these features, however exciting, were blurry. Their contours and details need filling in.

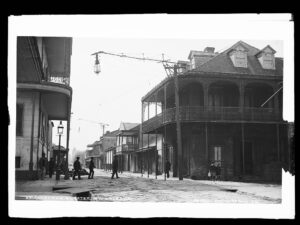

Calvin Trillin’s ode to New Orleans in the New Yorker, an account of his gastronomic expedition to the city, enticed me. My wife and I spent our honeymoon there, following Trillin’s lead and that of other writers. We snacked on red beans and rice at Buster Holmes’, a hole-in- the-wall in the French Quarter, celebrated by Trillin. We must have looked out of place when we asked for a menu and were given a barely legible list of items scrawled on butcher paper. On another day, I put on a required jacket and stood in line to dine at Galatoire’s, an institution of understated elegance, which paid homage to the city’s French and Creole culinary traditions. One late evening, we sat in the courtyard of the Napoleon House, a historic French Quarter establishment, savoring a muffuletta, one of New Orleans’s heralded sandwiches. We brought home a container of giardiniera, a mixture of olives, pickled carrots, celery, and tomatoes, from the Central Grocery Store. This relish frequently dressed the muffuletta.

For all this early immersion, I had just grazed the surface of the many layered city. When I began my investigation of America’s immigrant food, I chanced on a brief reference, a passing glance, in a New Orleans guidebook, to Progresso, a food business born in New Orleans. I knew Progresso mostly for its line of soups. I dug further and discovered that the company had been an early marketer of chickpeas, artichokes, roasted red peppers, and other Italian specialties that would later be displayed in the ethnic sections of supermarkets.

My curiosity whetted, I looked for more details. Progresso grew out of a peddling venture of Giuseppe Uddo, a young, adventurous Sicilian immigrant, who arrived in New Orleans in 1907 with his wife, Elenora. As a young boy, Giuseppe worked as a venditor, hawking olives and cheeses in his home town of Salemi and other nearby villages. After several false starts in New Orleans, he began vending cans of tomato paste, olives, and cheeses imported from his homeland. He carried them by horse and wagon to Italian truck farmers living on the outskirts of the city. Since Giuseppe refused to learn English, he depended on his horse, Sal, to guide him there. This was the beginning of Progresso, his son, Frank, told me. “The horse started the business.”

Uddo would team up with the Taorminos, another Sicilian clan who had opened an import business in New York City. The business marketed pomidori pelati (Italian peeled tomatoes), olives, and caponata, a favorite Sicilian appetizer, largely to small ethnic groceries. During World War II, Progresso shifted from imports to domestic production. The group bought a small factory in Vineland, in South Jersey, a heartland of Italian immigrant farmers. They canned and bottled roasted red peppers, hot cherry peppers, crushed tomatoes, and similar items. After the war, Progresso began searching for a year-round producer. They started making the country’s early ready-to-serve soups like minestrone and pasta e fagioli (pasta fazool), a mixture of broken-up pasta and beans in a tomato and salt pork sauce. Chain supermarkets now bought a larger share of the company’s products.

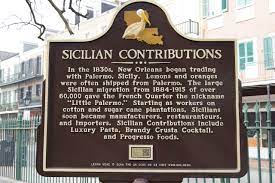

Uddo’s voyage to New Orleans was part of a larger migration that would reshape the Crescent City. By 1850, the town boasted the largest Italian community in America. The Italian population, with its predominantly Sicilian element, surged. Between 1880 and 1910, 50,000 of these immigrants streamed into New Orleans. Its semi-tropical climate, Mediterranean tempo, and Catholic traditions made them comfortable. They “recreated their world,” historian Joseph Logsdon observed, in this American Nice. The newcomers enhanced Creole cuisine with dishes like stuffed eggplant and artichokes and infused dishes with garlic and tomato sauce.

My image of New Orleans was also changing. This was not the town I had first encountered. I had largely missed the Sicilian influence in my early research. Why, I wondered, did this Sicilian bastion develop?

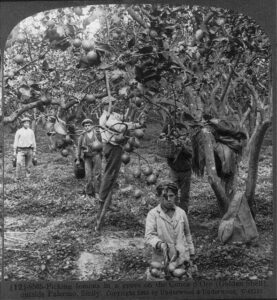

The boom in Sicilian immigration, I learned, was a result of the citrus trade, the transatlantic commerce in lemons and oranges. As early as the 1830s, the fruits were unloaded on the New Orleans levee across from the Mississippi River. Citrus, a much coveted commodity, was arriving in ships from the Sicilian ports of Palermo and Messina. Lemons bought and consumed in America before 1900, historian Justin A. Nystrom points out, were likely not grown in California but to have “come from Sicily and that a prosperous Sicilian immigrant had had something to do with it.”

I was familiar with the outlines of the trade from my earlier research. Nystrom’s book, Creole Italian, filled in its absorbing details. Nystrom tells the hidden story of the Sicilian passage to New Orleans. It was the pursuit of simple citrus fruit—not a quest for something grander, like riches, spices, or glory—that bound the Crescent City and Sicily together. The lemon not only propelled the trade but also the waves of Sicilian immigrants who settled in the port city.

The lemon was the “ideal trading perishable commodity,” historian Nystrom points out. The fruit could be picked while green and gradually ripen without spoiling on the long ocean voyage. Demand for the lemon in America was also strong. Countless recipes required lemon juice. Citrate, or citric acid, manufactured from the fruit, was indispensable to the canning process until a synthetic substitute was devised.

Anglo-American auction houses, Nystrom points out, controlled the early citrus business in New Orleans. It was not long, however, before savvy Sicilian merchants, capitalizing on their ties to the source of the fruit, began unseating the established traders.

After the Civil War, large cargoes of citrus were arriving in New Orleans, Nystrom notes. A load of fruit—6,855 boxes of lemons and 13,727 boxes of oranges—filled the ship Bessarabia, which docked in 1882. The Sicilian connection to the goods was obvious in the names of the commission merchants—Le Secco, Trapani, Randazzo—who ordered them. One Sicilian magnate, Angelo Cusimano, took the lion’s share of the fruit. Cusimano, who was also in the pasta business, purchased 5,849 boxes of lemons, 94 boxes of oranges, and 102 boxes of macaroni.

Other merchants concentrated on the retail side of the business. An 1860 ad for a grocery run by R. Tramontana, uncovered by Nystrom, advertised his stock. He was selling “creole oranges,” bananas, pineapples, along with other nuts and fruits.

By 1890, the Sicilians had finally pushed aside the older merchant families in the trade. The ethnics now held sway over the importing, wholesaling, and retailing of the business. Profitable opportunities abounded. Peddlers selling fruit often moved to higher rungs on the ladder.

An Italian colony sprang up in New Orleans. Ships carried fruit, and sometimes passengers eager to make their way into the citrus business. Like the Uddo family, Sicilians clustered in an area near today’s French Market. In “little Palermo,” Italian purveyors were increasingly selling their wares at its stalls. “A riot of smells,” writer Richard Gambino observed, the market was fragrant with “musty vegetables, pungent fruits, sweet flowers.” The citrus trade put New Orleans on the map for Sicilians eager to strike out on their own. Ships loaded with fruit often carried passengers who wanted to try their luck in the burgeoning industry. Many of the Sicilians getting off the S.S. Utopia, scholar Jean Ann Scarpaci points out, toted small containers of lemons.

The ambition of the Sicilians stirred resentment among fearful locals. Joseph Shakespeare, the New Orleans mayor, castigated the immigrants in June of 1891: “They monopolize the fruit, oyster and fish trades and are nearly all peddlers, tinkers or cobblers…. They are filthy in their persons and homes and our epidemics nearly always break out in their quarter. They are without courage, honor, truth, pride, religion or any quality that goes to make a good citizen.”

America’s partner in the citrus trade, Sicily, had been building a thriving lemon industry. Not native to Sicily, the lemon had actually begun its journey in the foothills of the Himalayas, where the trees grew, as one authority put it, “under the sheltering umbrellas of bigger trees.” The lemon was probably first cultivated in India. In the 9th century A.D., the Arabs on their imperial march colonized Sicily. They transplanted lemons and other crops like eggplant, spinach, and sugarcane to their possessions. The terrain in Sicily was hostile to a fruit that flourished in hot, steamy, and rainy conditions. Undaunted, ingenious Arab farmers set out to turn the arid land into a veritable oasis.

An intricate system of irrigation, based on aqueducts, ditches, and canals, channeled an abundant supply of water year-round for the soil. Author Helena Attlee describes the remarkable transformation of the land around the city of Palermo, the capital of the Arabs’ Italian colony, through the eyes of a Muslim traveler, John Hawqal, a Baghdad merchant. Spellbound, “he was moved by … the streams descending from the mountains to east and west, the water wheels lining their banks, and the land to either side of them planted with fruit trees, sugar cane, papyrus, and pumpkins.”

The lemon’s commercial breakthrough was hastened by the discovery of an English naval officer, James Lind. In a Treatise on the Scurvy, published in 1753, he argued that lemons were a cure for the illness, “the most effectual remedy for this distemper.” Fifty years later, the British navy required sailors to take an ounce of lemon juice sweetened with an ounce of sugar every day after two weeks at sea. Lord Nelson championed Sicily as a citrus source. “Some people remark,” Attlee notes, “that Nelson had transformed Sicily into a vast lemon juice factory.”

A contract to provide lemons to the British navy followed. Growers soon cast their eyes on America as a market for their produce. By 1857, over 19 million kilos of fruit, Attlee says, were shipped from Sicilian shores. In 1860, the wealth created by citrus farming in Sicily made it the most profitable agricultural business in Europe.

Tempted by the riches to be gained, farmers with more modest wealth started investing in a crop that had once been largely the domain of aristocrats. Speculators spotted easy opportunities to take advantage of unwary citrus growers. Mafiosi organized a protection racket to rob growers worried by the costs of their risky endeavor. Gangsters offered to help, supplying water and erecting water pumps. For those who feared for the safety of their valuable crops, the crime lords provided guards. Of course, there was always a price to be paid.

Failure to pay pizzo, the protection money, was risky and sometimes fatal. Offenders were met with violence. It was “exercised openly, calmly, regularly and as part of the normal course of events,” according to an 1876 report cited by Attlee. The curtain of citrus barely concealed places where savagery prevailed. A visitor “will see the place where a garden owner who wanted to follow his own plans for renting out his lemon groves felt a bullet passing just above his head by way of friendly warning.” The report said “the perfume of orange and lemon blossom begins to smell like corpses.”

Shipping fruit across the Atlantic was expensive. Steam-powered shipping in the late 19th and early 20th centuries came to the industry’s rescue. Speedier, more fuel-efficient “lemon boats” now carried heftier cargoes. “The most valuable fruit,” Attlee points out, “was carefully arranged in wooden “American-style boxes and wrapped in colored tissue paper.” The citrus cargo between Sicily and the U.S. soared to new heights. Between 1892 and 1894, Nystrom notes, 400,000 boxes of citrus fruit were unloaded in New Orleans.

Many of the ships were now carrying fruit as well as large numbers of Italian immigrants bound for labor in the sugar cane fields outside New Orleans. Pliant hands, the peasants were replacing a recalcitrant black work force. Their work was back-breaking toil, cutting cane with their machetes during the day and, at night, grinding, boiling, and refining their product. Unlike earlier immigrants, many of whom were prominenti, notables and men of means, these recruits were typically downtrodden commoners. According to a press account, one shipload arriving in 1896 was “laden with 34,000 boxes of lemons and 600 tons of sulphur with a supplemental immigrant cargo of 121 souls.” The labor bosses, the padrones, who corralled the workers, were often one time fruit traders with close ties to the island.

Shipping companies synchronized their schedules with the sugar cane season in Louisiana. Boats left Sicilian ports just in time for them to unload passengers in early October for the zuccarata, the sugar harvest, which ran from October to January, the “immigrant season.” The citrus trade, Nystrom concludes, paved the way for the massive immigration of Sicilians: “The Sicily lemon, not only brought the original Sicilians to New Orleans but established the trade routes that nearly all of their subsequent countrymen followed.”

The citrus bonanza would not last forever. Initially, there was no contest between the Sicilian lemon and the lemon grown in California. Vendors in a San Diego market in 1888, Nystrom notes, were almost uniformly dismissive of the American product. “The Sicily lemon is good, the California lemon is good—for nothing,” they told one observer. American growers did not surrender. They battled their Mediterranean rivals for supremacy in the market. A tough levy on imported lemons, the industry calculated, would knock the greedy Sicilians off their pedestal. The journal of the American Tariff League, Nystrom points out, sneered at the “competition.” “Among all the importers none are more persistent and vicious in their assaults on American industry than the firms, nearly all with Italian names, which are engaged in importing Sicily lemons.” By 1937, a crippling tariff on imported lemons achieved its objective. The California lemon had toppled the Sicilian.

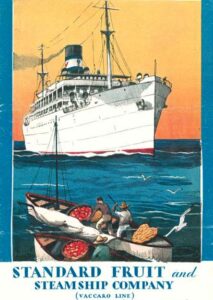

The loss of the citrus business did not hinder the Sicilians. Businessmen, many of whom had prospered in the fruit trade, threw themselves into a new field, marketing tropical fruit from Central America. Two families, the Vaccaros and the D’Antonis led the way. They banded together, first opening a small general store in Baton Rouge and then, after a flood in 1897 destroyed it, embarking on a new venture. They transported oranges, picked down river, in luggers, small boats, to New Orleans, for sale at the French Market. The clans again suffered another misfortune. A ferocious winter storm devastated the orange trees on which the business depended.

They decided to change course. “If we are to achieve our ambitions in life, there is not much left for us here,” Joseph Vaccaro said to his son-in-law, Salvador D’Antoni. “I understand that there are coconuts and bananas in Honduras.”

After some early forays to Honduras, they brought back coconuts, small loads of oranges, but only a few parcels of bananas. They soon got luckier, using steamboats to transport the more lucrative product, often carrying more than 200,000 banana stems a trip. The company rapidly captured the Honduras market. The enterprise expanded, acquiring and building its own railroad line, from the port to the fruit groves. The import trade took off. The small firm grew into a shipping colossus that became the Standard Fruit and Steamship Company in 1923.

The New Orleans elite, perhaps reluctantly, praised Standard’s success. The company helped make New Orleans the world’s largest importer of fruit in the early twentieth century. Over 600 notables gathered at the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans on October 5, 1925, to salute Standard’s contributions to the economy. St. Clair Adams, the president of the Louisiana Bar Association, lauded the owners for lifting New Orleans “out of the mud,” and transforming it into a “beehive of useful activity.” Once considered disreputable, Sicilians were at last given their due.

Notes

Justin A. Nystrom’s book, Creole Italian, was a treasure house of illuminating details about the New Orleans-Sicily connection. Helena Attlee recounts an absorbing history of the lemon, which is especially informative about the development of the fruit crop in Sicily. Jean Ann Scarpaci’s dissertation, Italian Immigrants in Louisiana’s Sugar Parishes, is a pioneering study of the ethnic labor force. My own book, The World on a Plate, tells the story of Progresso and examines the development of the Italian colony in New Orleans.