A small plane, something like a crop duster, landed in a southern New Jersey field on a culinary mission. In 1975, New York Times food critic, Craig Claiborne, had decided to observe firsthand a plant that he had grown increasingly curious about. The writer had come to Formisano farms, where four generations have been growing fennel since 1908. Gazing at the bountiful fields of this unique vegetable, prized by Italians and now gradually being discovered by inquisitive non-ethnics, Claiborne was captivated. The crop, he wrote in an article for the Times, was “caressed by a late autumn wind.” It “resembled a vast and undulating sea of green feathers.”

Claiborne watched intently as the workmen harvested the plant. “Ten workmen … are equipped with constantly sharpened carbon steel knives called cabbage knives. The fennel is lifted from the soil and, with one quick swoop of the knife to the underside of the plant, … the fennel is ready to be crated and labeled.” The family treated the visitor to a dish of sea bass baked in fennel. Claiborne relished the plate. He dubbed Ralph Formisano, the senior member of the family, the “fennel king.” The Times writer recounted his visit in the newspaper and his 1976 book, Claiborne’s Favorites. The Claiborne story paid dividends. “That put us on the map,” Ralph Formisano, the senior member of the family, told journalist Eileen Stilwell. (More on the Formisanos later.)

Claiborne had wanted to write about fennel after noticing how few Americans were acquainted with it. Writing in 1961, he spotted a customer mystified by an unusual item in a grocery’s vegetable counter:

It had a solid root end and its leaves were somewhat feathery. Timorously she asked a near-by clerk what it was and he answered “Fennel.” “How do you eat it?” she asked. “Raw.” It is regrettable that so few of the city’s inhabitants know of the vegetable and even fewer know its virtues.

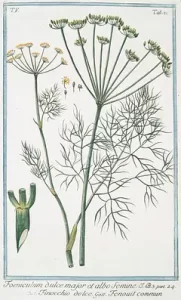

The variety of the fennel plant the Formisanos grow was first cultivated in Florence, Italy in the 17th Century. Florence fennel, the type most shoppers are familiar with, is distinguished by feathery fronds that spill out from its celery-like stalks and by the buxom bulb at its base. This feature makes it look like “pregnant celery,” as writer Maggie Stuckey describes it.

A versatile ingredient, fennel lends itself to a variety of tasty dishes. It goes particularly well with fish, as Claiborne discovered. It can be braised, steamed, or grilled. Paired with olives and oranges, and dressed with olive oil, fennel makes a piquant salad. Laced with fennel seeds, sausages and salamis are invigorated.

Native to the Mediterranean, fennel, like carrot’s ancestor Queen Anne’s Lace, grows wild in meadows and country roads. A cluster of brilliant yellow flowers, which yield aromatic seeds, form a parasol, or umbel, over the plant. Fennel shares this umbrella with other members of the umbelliferae family, like coriander, dill, and anise. Fennel, like some of its relatives, is infused with anethiole, an oil that produces a licorice-like fragrance.

Of ancient lineage, the plant was dear to the Greeks and Romans. Its name derives from the Latin foeniculum, or fresh hay, probably because of fennel’s lively scent. The Romans delighted in young shoots marinated in brine and vinegar. Fennel seeds were sprinkled in cakes and bread. Its licorice flavor, the Roman naturalist Pliny points out, was excellent for “seasoning a great many dishes.”

In the ancient world, the fragrant plant was more than a valued spice. Fennel, it was felt, made you lean and fit. The Greek name for the plant, marathon, has its roots in the word, maraino, to “grow thin.” Marathon, the location of the celebrated battle between the Greeks and Persians, food scholar Raymond Sokolov explains, got its name from the plant, which covered its fields.

Fennel was reputed to help soothe the stomach. Eating a stalk of fennel, Socrates recommended, could alleviate the upset. In India, fennel seeds were prized for similar reasons. After eating, many Indians today chew the seeds to settle their insides.

Fennel, it was claimed, was also especially helpful for the eyes. It sharpened eyesight and cured blindness, Pliny wrote. Snakes, he observed, rubbed up against the plant after shedding their skin. They were trying, he surmised, to regain their sight by getting the plant’s juice in their eyes.

In later years, medical commentators echoed Greek and Roman lore. “Both the seeds, roots, and leaves of our Garden fennel are much useful in drinks and broth for those who have grown fat,” the 17th Century English naturalist, William Cole, wrote.

In a similar vein, 17th Century English gastronomer John Evelyn urged his readers to eat the vegetable peeled like celery. The benefits: it “expels wind, sharpens the sight, and recreates the brain.”

The modern pairing of fennel with fish has earlier antecedents. Europeans, herbal scholar Maude Grieve observed, enjoyed it as a “condiment to accompany salt fish during Lent.” Botanist John Parkinson praised fennel’s gifts to both “meal and medicine.” It “helpeth to digest the crude quality of fish and other viscous meats.”

Chewing fennel seeds also alleviated hunger, according to other authorities. A godsend to the poor, English garden historian Alicia Amherst pointed out, the destitute considered fennel as “a relish to unpalatable food.” In North America, Puritans turned to “meeting seeds,” dill and fennel, to endure long sermons and aching stomachs at church.

In Italy, the name for the plant, finocchio, recalled the ancients’ trust in its vision improving qualities. Food historian Raymond Sokolov offers a translation of the word. It is a “contraction” for “dainty eye.” The word, he says, gradually became Italian slang for “homosexual.” Trading on the slang term, a late night club in San Francisco’s North Beach, famous for its female impersonators, called itself Finocchios.

Finocchio was linked to flattery and dissembling. The expression, “dare finocchio,” means to “give fennel” or flatter.

In Shakespeare’s England, fennel took on a similar allusion. In playwright Ben Johnson’s play, The Case Altered, Christopher and the Count have this exchange:

Christopher: No, my good lord.

Count: Your good lord! Oh! How this smells of fennel!

The Italians grew increasingly passionate about this fragrant vegetable. Giacomo Castelvetro, the 17th Century culinary writer, spoke of the verve it brought to social gatherings:

We preserve quantities of fresh fennel in good white wine vinegar and eat in summer and in winter when offering drinks to friends between meals. We also serve this pickle with fruit in special occasions, when fresh fennel is not to be had.

Fennel’s fame spread throughout the English-speaking world. In the U.S., the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote rapturously about it:

Above the lowly plants it towers,

The fennel, with its yellow flowers,

And in an earlier age than ours

Was gifted with the wondrous powers

Lost vision to restore.

It gave new strength, and fearless mood.

In America, Jefferson was an early admirer of the plant. Thomas Appleton, an American consul in Naples, Italy, sent the Virginia planter some fennel seeds in 1834. Thomas Jefferson wrote a lyrical letter in response:

[The] fennel is, beyond every other vegetable, delicious. It greatly resembles in appearance the largest size celery, perfectly white, and there is no vegetable that equals it in flavor. It is eaten at dessert, crude (raw), and with or without, dry salt. Indeed, I preferred it to every other vegetable or to any fruit.

Still, for many years, fennel was unknown to most Americans. If recognized at all, it was regarded as an ethnic vegetable, the province of Italians. Before it graced sophisticated dining tables, it was grown by Italian immigrant farmers. In the early 1900s, Giovanni Formisano, one such pioneer, left his village near Naples, where his family grew the plant. Arriving in New York City, he landed a job on the railroad. He labored long hours for a dollar a day, his grandson John Formisano, Sr. recalls. Tiring of the toil, he searched for more fulfilling work. Pursuing his love for tilling the soil, he was a hired hand for several New Jersey farmers. By 1908, he had saved enough from his meager earnings to buy his own piece of land in Carlstadt, a North Jersey town.

Drawing on childhood memories of his homeland, Giovanni started cultivating Swiss chard, romaine lettuce, celery, and, of course, fennel, to name a few of his crops. He brought his goods to sell at the 14th Street market in Manhattan. As John tells it, Giovanni drove his horse and wagon to Hoboken, New Jersey, where he took the ferry to the city. The wagon was loaded with barrels of cabbage and flats of fennel stacked three feet high, crammed in with other vegetables. His prime customers were small, ethnic vendors who arrived at the market with their pushcarts. Each group had its own preferences—Germans for cabbage, Italians for escarole, dandelions, endives, and fennel. Some shoppers came home with bushelfuls of plum tomatoes. After an exhausting day, John says, Giovanni would take the ferry back and quickly fall asleep in his wagon, trusting his horse to get him home. Over time, Giovanni sold his wares at markets in Newark, Paterson, and other cities.

As his business prospered, the budding farmer could afford new vehicles. A tractor replaced the horse and wagon. In the late ’twenties, he bought a Mack truck and a Model T. His repertoire expanded. During the ’twenties, John points out, he started selling basil for a quarter a bunch. The plant, loved by Italians, came in one pound coffee cans.

Formisano’s, which moved first to Moonachie in North Jersey and then to its present location in Buena, a South Jersey town, is in the heartland of Italian farmers. Early settlers from southern Italy got their start as strawberry or raspberry pickers or as railroad workers in the late 19th Century. Many immigrants also took jobs as farm laborers. Whatever route they took, their goal was to save enough to own their own land. They were not stymied by the sandy soil of the Pinelands region of South Jersey. As older farmers retired, Italians replaced them. Two substantial colonies of the immigrants sprang up, one in Vineland, the other in Hammonton, two towns not far from the Formisano farm.

Emily Meade, a sociologist and mother of anthropologist Margaret Mead, visited Hammonton in 1907 and marveled at the novel produce the farmers were harvesting: “Italians have popularized the sweet pepper and introduced … a peculiarly shaped squash, okra, Italian greens and various kinds of mint.” Hammonton often claims to be the “most Italian” community in the U.S. (Emily Meade’s name is often spelled this way in publications, but in other instances it is spelled Mead.)

Most of the farmers in the area are still of Italian heritage. The people in Vineland keep their culture alive with an annual Spring festival featuring a Dandelion dinner where an array of foods and drinks made from the plant are enjoyed. The menu might include a salad with dandelion greens, dandelion ravioli, and ice cream with dandelion brandy. The town, where dandelion wine is a not uncommon refreshment, calls itself the “Dandelion Capital of the World.”

Formisano Farms, one of the oldest in the area, has burgeoned into a full-scale enterprise purveying a wide variety of produce. Food brokers and wholesalers, supermarket chains, and gourmet shops snap up their wares. “We don’t have to knock on doors anymore. We’ve got enough business,” John Formisano, Sr. who grew up chopping celery in the fields, told reporter Stilwell.

Formisano’s, Richard Vanvranken, the Rutgers University agricultural extension director for Atlantic County, observes, is a groundbreaking enterprise, “introducing specialty herbs and fresh market herbs to the Vineland region of South Jersey.” “When the Formisanos arrived, production in the region was mostly of summer/fall staples like peppers, tomatoes, sweet corn and sweet potatoes. Spring and fall greens opened new markets and extended the production season for the region’s small farmers.”

Formisano’s accommodates both older generation ethnics and customers with more contemporary tastes. To please stalwart Italians, the farm offers them escarole, dandelions, and endives. Some of these buyers ask for finocchio, not fennel.

Always alert to culinary trends, “they like to try anything new and different to open new markets,” Vanvranken points out. Parsley, he adds, was a “multi-million dollar crop when I arrived forty years ago … but by the late ‘80s, cilantro, that no one had a clue about, was being grown just as much.” Cilantro joined basil and arugula as a Formisano staple.

Their renowned fennel crop has its peak season during the fall. The greatest demand is from September through Thanksgiving and sometimes, if it isn’t too cold, till Christmas. During this period, the tempo at the farm is especially brisk. That is “when it moves,” John Formisano, Sr. says.

Never complacent, the partners are keenly attuned to the changing tastes new immigrants are bringing to the marketplace. Indian shopkeepers who first came looking for eggplant began seeking more unusual plants. Fenugreek, or methi, was at the top of the list for the “Indian people,” John notes. The herb, used in a variety of ways in the country’s regional cuisines, is especially treasured for its leaf. When harvested, John points out, fenugreek should only be picked when it “sports a nice green leaf.”

The Formisanos rode the wave of fennel’s rising popularity. Once considered exotic or simply as an Italian delicacy, it now has cachet. Upmarket hotels and restaurants are enlivening their menus with fennel dishes. The Atlantic City Borgata Hotel, 30 miles away, began ordering fennel and other unique items like candy-striped beets and Sicilian oregano from them. The Borgata’s dining room created a fennel tempura, sprinkled with lime juice and sea salt.

However, there is still more marketing to be done. The uninitiated sometimes confuse fennel with anise, which has a somewhat similar taste. To prevent confusion, the Formisanos label some cartons of fennel as “anise.”

Fennel is savored in the Formisano household. John, Sr.’s wife Mary often makes a carrot and fennel soup. More than anything, John enjoys the simple pleasure of a snack Italians call pentimento. He nibbles slices of fennel cut from the bulb, dipped in olive oil. It’s something to relish, he says, “while watching a ballgame.”

Acknowledgments

Anita Formisano, who runs the Formisano office, was very helpful. I am grateful to John Formisano, Sr. for taking time away from his labors to talk with me. Thanks to Richard Vanvranken, the Rutgers Agricultural Extension Director for Atlantic County for facilitating my introduction to Mr. Formisano and for sharing with me his insights and observations about farming in the Garden State.